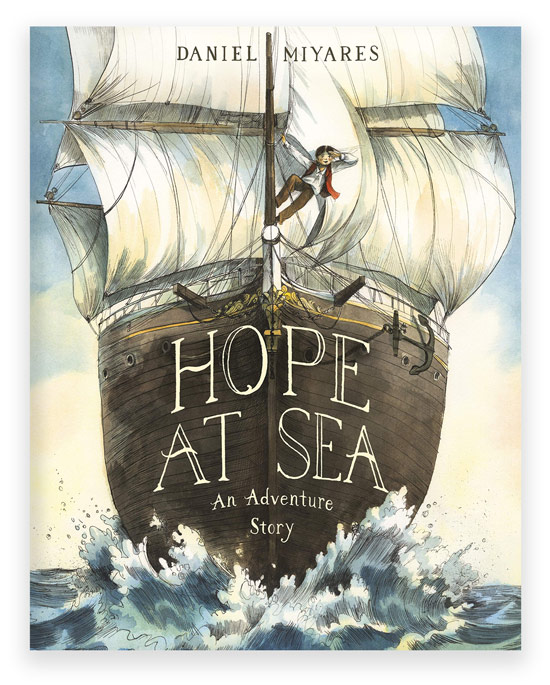

“What do we do when the storms of life come?” Critically acclaimed author/illustrator Daniel Miyares points to that key question as the initial idea for his picture book, Hope at Sea (Anne Schwartz Books, 2021). The story follows high-spirited Hope, a young girl whose determination to experience an adventure causes her to stow away on her father’s nineteenth-century merchant vessel. But as is often the case, Hope discovers that along with excitement, the journey also holds hard work and even danger—a great entry point to a discussion with young readers about navigating the tumultuous voyages of their own lives.

Here, Miyares talks with Lisa Bullard about helping young people meet life’s challenges, the process of creating books, and his advice for young writers and illustrators.

Daniel Miyares’ family

Resilience is one of the clear themes in Hope at Sea. What inspired you to write about hope and resilience?

I love that you mentioned resilience. It just seems so essential right now. A few years ago, I was sitting at the kitchen table with my daughter after school. We were talking about and unpacking all of the things that were weighing on her from the day. She had to change schools three times in three years, and it was hard on her. As I was listening to what was on her heart, it occurred to me that no matter how much I wanted to protect her from all the hurts and difficulties that would come her way, I just couldn’t. I figured that maybe the best thing I could do is to help encourage a sense of resilience. After that I started thinking about the initial idea for Hope at Sea: what do we do when the storms of life come?

I figured that maybe the best thing I could do is to help encourage a sense of resilience.”

What was the artistic process that led to the book’s exquisitely detailed illustrations?

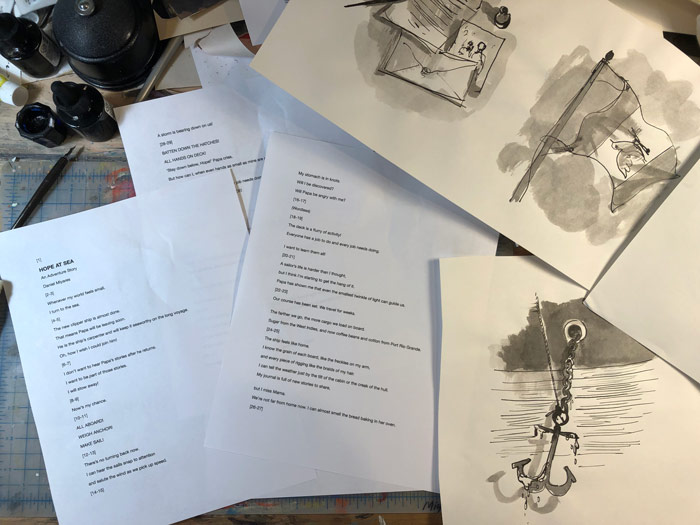

I made the illustrations using pen, ink, and watercolor. I try not to go into a project with a set idea of how I’ll approach the art. Usually I begin with my research and sketches, then try to figure out what rings true to the spirit of the story for finished art. For example, while working on the sketches for Hope at Sea, I used pen and ink to make my quick studies. Anne Schwartz and Art Director Nicole de las Heras saw my sketches and asked if I had considered looking at scrimshaw artwork from that time. I thought that was a great way to lean into my love of ink drawing, speak to that era, and leave lots of room for details in the illustrations.

What’s your favorite part of the book-making process?

I love the process of making books for different reasons at different stages. The sketch phase of making a book is always really exciting to me because there’s so much exploration and discovery—plus drawing is my happy place. For Hope at Sea, the researching that went into it was extremely challenging, but also invigorating. I feel like making books is such a gift because I get to investigate so many different subjects.

You’re both the writer and illustrator of Hope at Sea, but you also illustrate stories written by other authors. How do the two approaches compare?

My entry point into a story is often through the visual narrative. I think that’s true for books I both write and illustrate as well as those that I only illustrate. When I’m working on a new manuscript for a book, I can’t help but do thumbnail drawings alongside the writing (even if I’m not going to show them to anyone) to try to understand the heart of my story. They go hand in hand in my mind. I like to have both kinds of projects on my schedule each year because I have so many ideas I want to share as an author/illustrator, but when I illustrate other people’s manuscripts, it takes me places that I didn’t expect to go. It challenges me as a person … and that’s good.

When I illustrate other people’s manuscripts, it takes me places that I didn’t expect to go.”

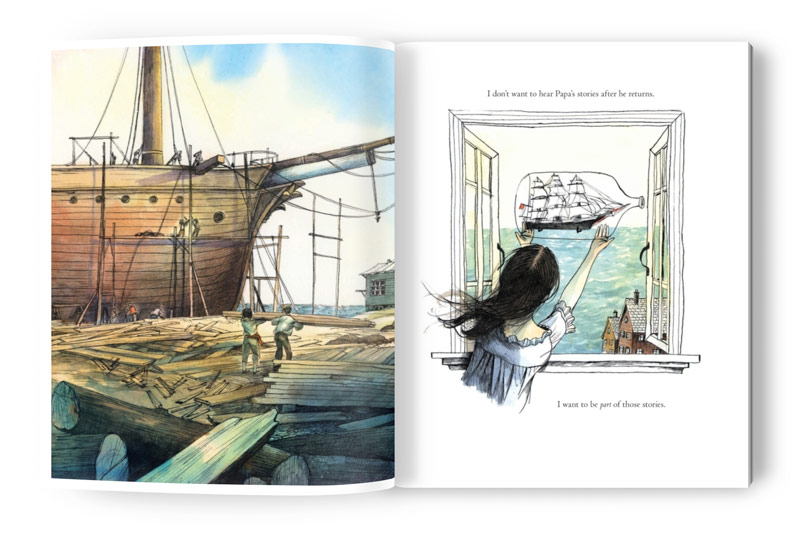

I’m fascinated by how you redirect a reader’s focus in your stories by changing the perspective from which they view a scene. What is the process that you go through to determine the viewpoint for each illustration?

I definitely go through a lot of trial and error during the sketch phase of my projects to figure out how I want to compose my images. I grew up with a big love of movies. I feel like designing with a printed page is similar in a lot of ways to what a cinematographer does with a camera frame—especially when you add in the use of panels and page turns. How and where you place the reader has a huge impact on the emotional power of an image. I try to consider that with each illustration. There’s really nothing to lose by trying variations of scenes at the thumbnail stage. I do probably hundreds of small drawings to figure out the “camera angles” that feel right for the story. I also ask myself a lot of questions about the story during the process. Is this a quiet introspective moment, or is it an action-packed dramatic scene? Is it a moment that I want the viewer to process quickly, or do I want them to linger? It’s always exciting when you can feel the drama with just a tiny three-inch sketch.

What’s it like to tell a story using only pictures?

I suppose when I’m using just pictures to tell a story, I’m not thinking about what needs to be said for the reader to understand, but rather what needs to be felt to understand. Wordless books for me are developed and planned with emotional beats—if that makes sense? My job is to try and make sure the images hit those beats as effectively as possible.

I’m not thinking about what needs to be said for the reader to understand, but rather what needs to be felt to understand.”

Do you have any suggestions for activities that educators can use to teach students how to tell stories through their art?

I often do an activity in my sketchbook that I call past, present, and future. To start with, I draw a moment of something happening. Subject matter could be anything really—a character, a place, and something going on. Then I simply imagine what happened just before that moment, and then what should happen just after that moment. Thinking of your art as a specific moment of time can help get you in the visual storytelling frame of mind, I believe.

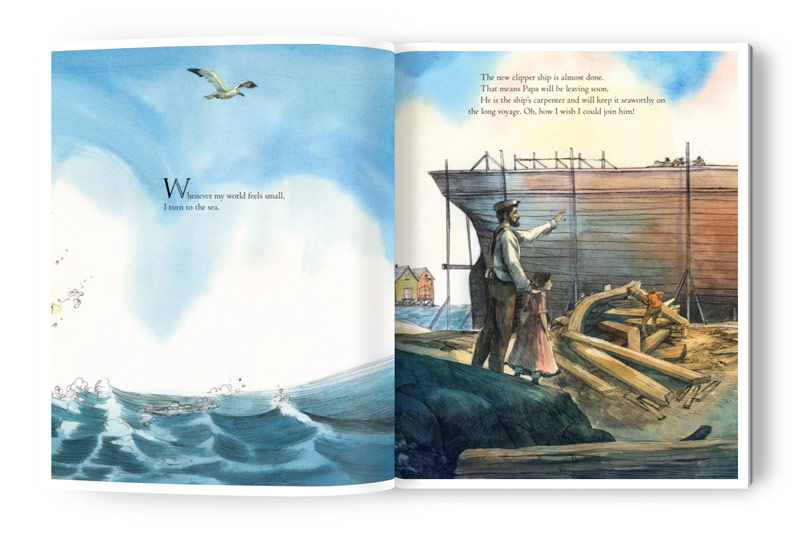

Interior spread from Hope at Sea

Hope at Sea is historical fiction, and you have also illustrated several nonfiction titles. Can you talk about your research process?

Sure, my research process is always evolving. I often do my researching in stages. Once I decided that I wanted to have Hope at Sea take place in a specific time, I did a real general period of discovery. I went to the libraries and the internet to see what ship building and sailing life was like then. Just a lot of reading that was easy to put my hands on. That sort of inspired me enough to work through some initial sketches and a manuscript pass.

After I have that first blush of a story down on paper, I really can see how much I don’t understand or know about a thing. That’s when I can make decisions about how to invest time, money, and effort in discovering new things. A good example was that I needed to have a more detailed understanding of how clipper ships were built in the early to mid-1800s. Photographs and drawings from the time are a little tough to decode, and even seeing them in person doesn’t show you how they were created, so I purchased a big thick book of published clipper ship plans from the 1800s. I could see board by board how the ship would have been constructed and why. I had to spend many hours figuring out just what went into making one of those majestic vessels so I could try and represent it as just a matter-of-fact part of the story. I didn’t want my representations of the time to be a distraction for readers.

Interior spread from Hope at Sea

Do you find it more or less complicated to illustrate something that draws on factual information—or to start with a “blank visual slate” in the case of a fictional story?

I do think it’s more complicated on the front end to illustrate something that’s based on factual information, but once you’ve done the research and the details are in place, it can be pretty liberating to create within that world. With fictional stories, the challenge for me comes in trying to back my way into the same immersive level of detail but from my imagination.

What’s your best advice for aspiring young authors and illustrators?

This is always a challenging question for me, because so much of making it as an author/illustrator seems to rely on you managing and leveraging your brand in your own unique way. The thing, though, that seems like it will always serve you well is the craft of what you do. If you want to be an illustrator, keep a sketchbook with you all the time. Draw in it. Write in it. Be curious. If you want to be a writer, keep a notebook and write every day. Be curious. Read as much as possible. The more you invest in making things no one has told you to make, the more you’re going to understand yourself as a creative person. That will hopefully lead you to the paths you should go down to get to where you want to go.

Be curious. Read as much as possible.”

What would you like to tell your fans about your upcoming books?

Well, I just had a new book come out (April 2022) that I illustrated that’s written by the fantastic Carter Higgins and published by Chronicle Books, called Big and Small and In-Between. Coming up in January of 2023, I have another one that I illustrated that’s written by the wonderful Anne Wynter and published by Balzer + Bray. It’s called Nell Plants a Tree. Now I’m working on my newest book as author/illustrator with the one and only Anne Schwartz. It is my first graphic novel. It’s based on my father’s childhood escape from Cuba in the early 1960s.

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

Readers can connect with me on Instagram @danielmiyaresdoodles, on Twitter @danielmiyares, or through my website, danielmiyares.com.