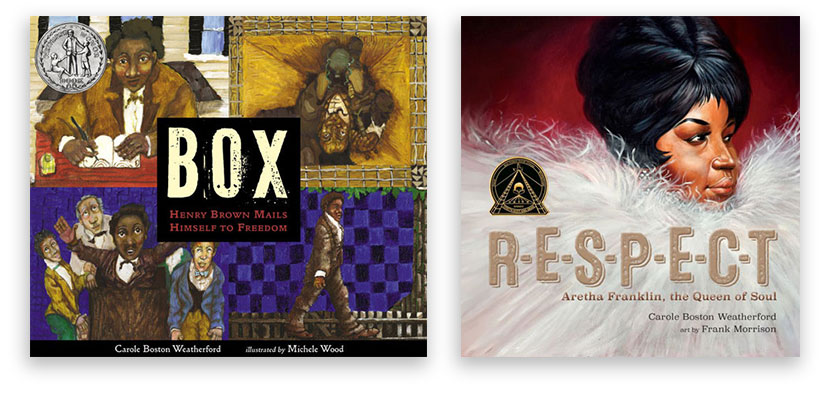

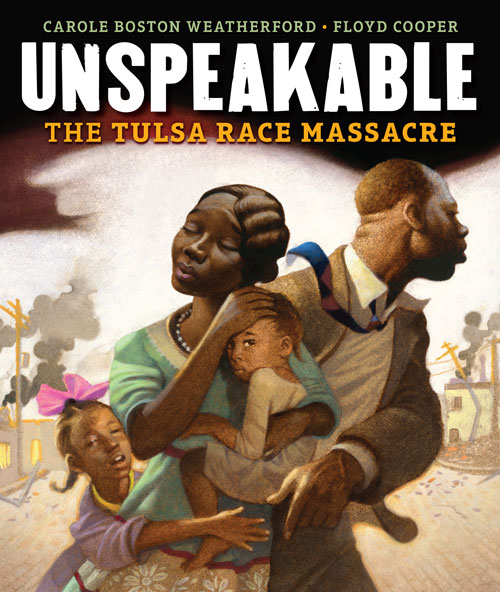

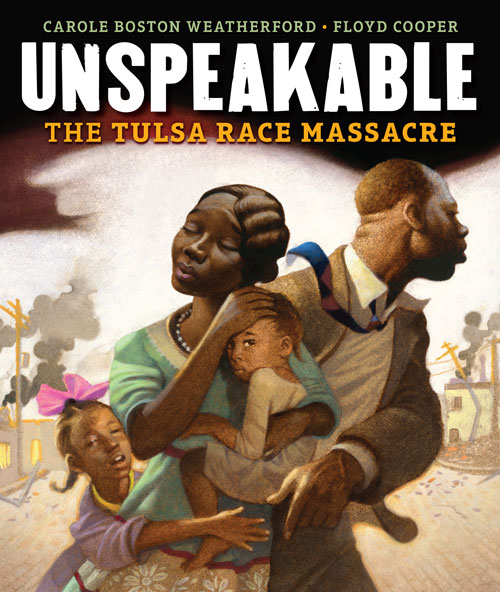

The new year is off to a spectacular start for Carole Boston Weatherford’s books. Her title BOX: Henry Brown Mails Himself to Freedom was named a 2021 Newbery Honor Book. The same day, her picture book R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul was honored with the Coretta Scott King (Illustrator) Book Award. And her newest book, Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre (just published February 2nd) has already been recognized with six starred reviews. Here, Weatherford talks with Lisa Bullard about that groundbreaking new book, the devastating event it depicts, and the thing she believes “sings the heart’s song.”

Your new book, Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, takes an unflinching look at an important historical event that is known to too few Americans despite being one of our nation’s worst incidences of racial violence. What brought you to this story?

The Tulsa Race Massacre resonated with me because I grew up listening to Billie Holiday’s protest song “Strange Fruit”; the 1898 Wilmington Massacre occurred in my adopted state of North Carolina; and my family’s lore includes a racially motivated arson and a lynching.

I was also inspired by my last meeting with the late illustrator Tom Feelings (the first African American artist to win a Caldecott Honor Award for Moja Means One: Swahili Counting Book). He shared with me illustrations for a work-in-progress about lynching.

Many of your titles highlight people who have been under-represented in history books, or as is the case with Unspeakable, events that have been too long overlooked. Do you have any suggestions for educators who are committed to teaching their students about lesser-known stories like this one?

Much African American history has been omitted from K-12 and college curricula. Sadly, teachers can’t teach what they don’t know. But that doesn’t mean the subjects don’t hold important lessons. Teachers must first educate themselves. Fortunately, children’s books can serve as a cheat sheet and a crash course. Teachers can discover these narratives along with their students.

“Much African American history has been omitted from K-12 and college curricula. Sadly, teachers can’t teach what they don’t know. But that doesn’t mean the subjects don’t hold important lessons. Teachers must first educate themselves.”

You often write about complex and difficult topics, but you handle them with such grace that the resulting books resonate even with readers who are quite young. How do you pull that off? Have you ever had to set aside a topic because you couldn’t find a way to make it approachable for young people?

I do not think that children are too tender for tough topics. So, I don’t condescend to young people. Children deserve and will demand the truth.

But I do write with their sensibilities and knowledge base in mind. Poetry allows room for creativity in crafting kid-friendly approaches. Sometimes, it’s about having a young narrator or having a through line to connect complex political concepts or social constructs.

Carole visiting at schools

I often tackle subjects years after learning the history myself. The subject simmers in my mind until I am able to envision a children’s book. The publishing industry is not always ready, though. I have been pitching a manuscript for years about the doll test that helped sway the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. It’s a difficult subject, especially because colorism persists today.

“I do not think that children are too tender for tough topics. So, I don’t condescend to young people. Children deserve and will demand the truth.”

Your mission, as you define it on your website, is: “To mine the past for family stories, fading traditions, and forgotten struggles.” Do you have suggestions for students who would like to uncover their own families’ stories?

Ask questions of elders; document what they tell you. Write down their responses, and if possible, record the interview. What you can learn from your family will be far more meaningful than any TikTok video.

Carole with her family

Poetry infuses all of your books—many of your titles are written as poems, and all of them draw on your innate lyricism. What’s the special power that poetry holds for you as a writer?

Since childhood, I have loved the music of poetry. Poetry tickles the tongue, trains the ear, and sings the heart’s song.

“Poetry tickles the tongue, trains the ear, and sings the heart’s song.”

Do you have suggestions for ways that educators and librarians can provide their students or community members with more of that “heart’s song”?

Teachers can use a poetry collection or anthology to launch a poem-of-the-week project. They can alternate with students in choosing a focal poem for each week of the school year, and then read it aloud and enjoy.

There are children’s poetry books connecting to every core subject. Chances are there is a poem that can provide context for whatever unit is being studied.

Last but not least, don’t kill the poem with analysis.

It’s truly inspiring how many of your titles were published in 2020, and 2021 seems to be off to a similar start. On March 9, you have another picture book slated for publication called Dreams for a Daughter (Atheneum, 2021). I particularly love this line from the book: “And you learn that asking the right questions means more than knowing all the answers.” Would you like to say more about that?

Dreams for a Daughter is a companion to In Your Hands, which was a Black Lives Matter prayer for Black sons. Because I have a son and a daughter, I was obliged to complete the pair.

That line from Dreams for a Daughter sums up my teaching philosophy. In the information age, young people are overstimulated and underinformed. Children are naturally inquisitive. But the older children get, the more hesitant they may be to ask questions. My books are tailor-made for critical literacy. It’s up to teachers to provide anti-racist books and to foster a climate for cross-cultural conversations.

That line from Dreams for a Daughter sums up my teaching philosophy. In the information age, young people are overstimulated and underinformed. Children are naturally inquisitive. But the older children get, the more hesitant they may be to ask questions. My books are tailor-made for critical literacy. It’s up to teachers to provide anti-racist books and to foster a climate for cross-cultural conversations.

“Children are naturally inquisitive. But the older children get, the more hesitant they may be to ask questions.”

What else what you like to share with Mackin readers?

I love connecting with young readers. These days, I do so through virtual visits. Often, I present with my son, Jeffery Weatherford, a children’s book illustrator and spoken word poet. We collaborated on the verse novel You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen. Next up from us is Call Me Miss Hamilton: One Woman’s Case for Equality and Respect (Carolrhoda, 2022).

Later this year, you can look for my book The Faith of Elijah Cummings: The North Star of Equal Justice (Random House Studio, 2021).

As a part of this interview, we’ve included an excerpt from your Author’s Note for Unspeakable. It provides a concise and insightful summary for educators and librarians who will want to dig deeper into this story. Mackin readers can also find many helpful resources in this extensive “Discussion Guide for Educators and Parents: Unspeakable,” written by Dr. Sonja Cherry-Paul.

What other suggestions do you have for those who want to better inform themselves about the Tulsa Race Massacre?

Like many book ideas, Unspeakable was on my heart for years before I wrote a single word. Learn more in this video. Libraries and schools can access online resources to study the massacre. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, Oklahoma Digital Prairie, Tulsa World newspaper are good places to start. There is also a CBS “60 Minutes” segment on the massacre.

It’s important to depict the 1921 massacre as part of a continuum of hate violence that includes present-day police brutality.

Connect With Carole Weatherford

Exclusive Excerpt

May 31-June 1, 2021, will be the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Here, Mackin readers get an exclusive online look at a portion of the Author’s Note for the picture book Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre. In this excerpt, author Carole Boston Weatherford provides important background information about the event.

Nationwide, racial tensions increased when World War I ended in 1918. African American soldiers who had fought and shed blood for their country hoped to receive greater respect back at home. But they did not. Violence against African Americans broke out in numerous cities and states in the summer of 1919, which became known as the Red Summer. Regardless of the supposed cause, the white mobs’ motives were always to limit Black political and economic progress and to reassert white supremacy.

Then, on May 30, 1921, in Tulsa, Dick Rowland, an African American teen, either stumbled or stepped on the foot of Sarah Page, a young white elevator operator in a downtown office building. Page screamed, and the next day Rowland was jailed. A newspaper report that Rowland assaulted Page stoked existing racial tensions, inciting a white mob, initially numbering in the hundreds, that was bent on lynching the teen. Black men and boys were frequent victims of white lynch mobs that publicly murdered them, often by hanging, for alleged offenses. A smaller number of Black residents came to the courthouse where Rowland was being held in an effort to protect him. When the sheriff refused to surrender Rowland, the white mob, which had been increasing in number, turned violent.

After a night of scattered attacks, at dawn the mob invaded the Black community, burning down at least 1,250 homes and two hundred businesses, and robbing and looting hundreds more. The sixteen-hour massacre claimed countless lives. Among the dead was an African American boy shot in a movie theater. Many victims were buried in unmarked graves.

Even before the smoke had cleared, police dropped the charges against Dick Rowland, and he was released from jail. He left town the very next day, reportedly for good.

Exact numbers of fatalities, casualties, and participants are unknown because public officials at the time focused on covering up the massacre rather than documenting it. Not until the twenty-first century was this tragic chapter of history even taught in Oklahoma schools.

Copyright © 2021 by Carole Boston Weatherford, excerpted from the Author’s Note for Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, used by permission of the publisher, Carolrhoda Books

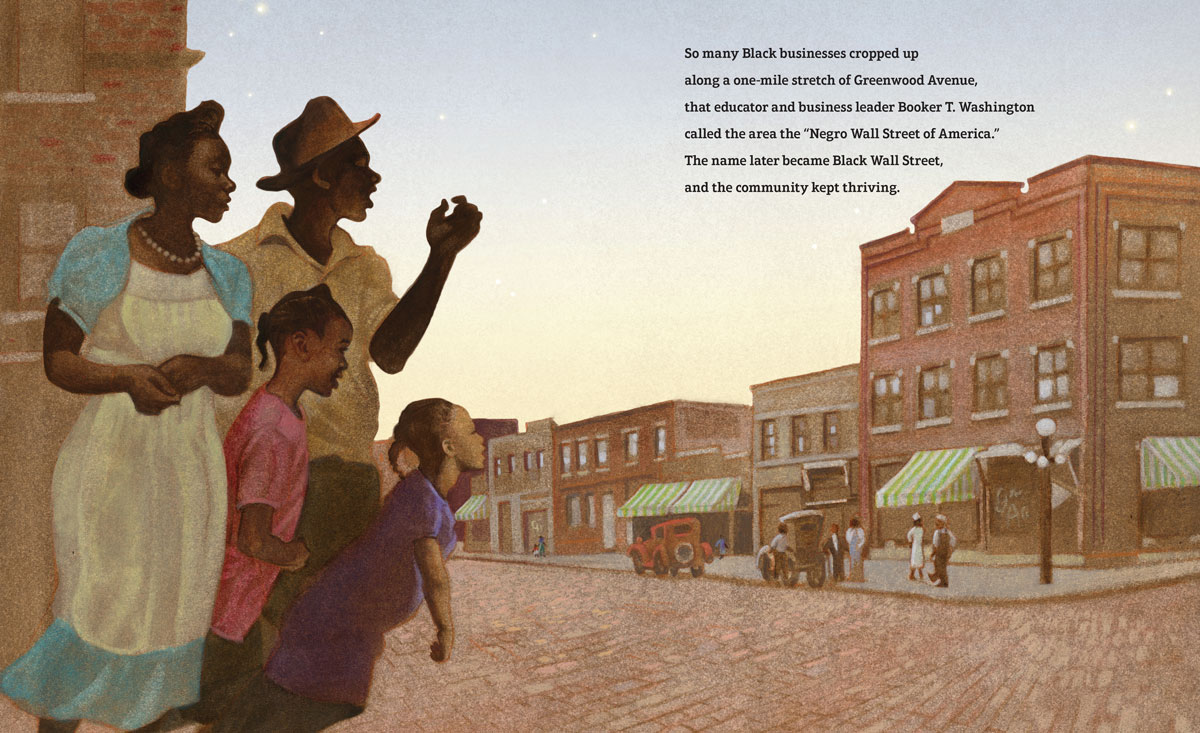

Interior spread from Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre

Text copyright © 2021 by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrations copyright © Floyd Cooper, from Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, used by permission of the publisher, Carolrhoda Books