Comics are kind of like that one “weird” kid in school no one knows how to be friends with.

As a medium, it’s studded with unfortunate tropes. The ubiquitous caped crusaders, the artsy middle-aged French unfortunates, the black-and-white Japanese cutesy teens, the fiery counter-culture stuff your suave aunt might pull a sly, knowing grin about. Comics are unapologetically strange.

But comics are also THAT kid: the one who can be friends with anyone.

And they’re everywhere. Comics are comfortable lounging in a history book, creeping behind your phone screen, and loitering on the street corners of the internet all the same. Every shade of story, every type of genre imaginable is found in comics. And every kind of person can enjoy them.

As a human race, we are reading visual cues long before we even start thinking in our native language. It’s a mother tongue spoken instinctually and so immediately, oftentimes we never even realize we’re interpreting, speaking, and listening in a visual way. Visual literacy is a language that crosses cultures and time to bring us something of what makes us human.

The way that we use language and the way we interpret stories is ever-changing. With the internet, memes, pop culture, advertisements and social movements, visual literacy is more important than ever.

We have never lived in a world where we can get through with the power of written language alone. We also must have a basic, rudimentary knowledge of how to interpret symbols- emojis, GIFs, art, illustration, social media, icons, memes, advertisements, logos, political caricatures, mascots, even the bathroom sign.

As the Toledo Museum of Art states on its website, “… [W]e need to learn to identify, read, and understand images – to become literate in visual language – in order to communicate successfully in our increasingly image-saturated culture.” (Toledo Museum of Art 2020).1

In the visual, and oftentimes symbolic, world we live in, it’s vital to be able to interpret and communicate with both imagery and text. But perhaps even more pressing is the need to develop the skills to analyze and shape the way we communicate with these tools. We’re already unconsciously interpreting ideas in a visual form, soaking them in on a daily basis. So why not prepare students to intentionally interact with them? We can start developing visual literacy with comics.

For the purpose of this blog, “comics” is being used as a catch-all term- it includes graphic novels, webtoons, manga, manhwa, comics books, and more. Just think of stories that are told visually. They’re immediate, accessible, and oftentimes can be devoured in mere hours. But just because comics are more accessible than regular texts or we process information in images instantaneously doesn’t mean comics are easy to teach or interpret on a higher-level. It would be a mistake to label comics as the cheap or simple path to literacy for nontraditional learners. Comics present unique challenges to students to not only interpret text, but also another layer of meaning to interpret: the art.

Grasping the meaning behind an image is made even more challenging by the text itself. Sometimes it’s communicating the same thing as the image, but not always. In fact, the visuals themselves are only the top layer of the vast meaning behind an image- piled on top of them are historical, written, and cultural subtext, all of which our brain interprets nearly effortlessly.

Meanwhile, traditional text leaves the imagery up to the imagination of the reader. That isn’t to say comics need to replace or even occupy the same space as traditional reading in the classroom. Neither medium is better or worse. However, we unfortunately often give comics the same place as picture books in teaching students to interpret texts.

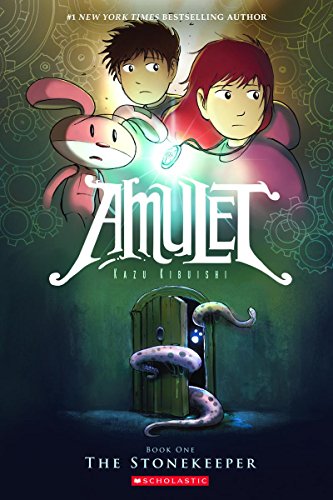

Some stories can only be found in comic format. We should consider this decision as very intentional by authors. Why not just write a book? Consider the cheesy, easy romance of Ngozi Ukazu’s Check, Please!, and Tomoko Schichihenge‘s the Wallflower series, the sobering memories of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the wildly creative journeys of Kazu Kibuishi’s Amulet, Skottie Young’s Middlewest or Jeff Smith’s Bone, the sly, off the wall humor of Dav Pilkey’s Adventures of Captain Underpants, the sharp wit of Noelle Stevenson’s Lumberjanes, the adventures and action of series like Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, Masashi Kishimoto’s Naruto, Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist, Rumiko Takahashi’s Inuyasha, Kohei Horikoshi’s My Hero Academia or Kami Garcia’s Teen Titans, or any of the plethora of titles on apps like Webtoon or ComicsPlus.

If these stories were written as a book, they would have ultimately been changed and therefore been a different story altogether. The way we tell stories changes the stories we tell. And as with any reading, stepping into another’s rich culture and diverse storytelling promotes empathy. Comics are where history meets art meets underground movement smashed up with all the immediacy and fun of imagery.

And why should we ignore fun while learning, as if engagement were the antithesis of higher-level thinking?

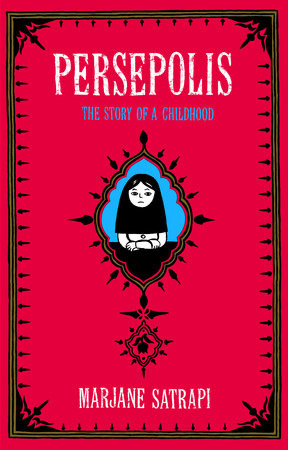

Why not bust out First Second’s Science Comics series while studying Geology? Or Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis in Global Studies while discussing the Arab Spring? Or Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales in History? Or Mariko Tamaki’s Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me while discussing unhealthy relationships in high school Health class?

Don’t be afraid of the “weird” kid. They’re actually really cool. Dust off your keyboard or crack open that slippery copy of Ryan North’s The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl your niece left at your house. Bust down the door to communication beyond the traditional. It might feel awkward at first, and take some time to get used to the style and format of these stories. But they are very much worth reading.

References:

1 Toledo Museum of Art. 2020. “Why Visual Literacy?” Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.toledomuseum.org/education/visual-literacy/why-visual-literacy.