Children’s book author Laura Purdie Salas shares how to create an engaging and safe writing space in the classroom. Read on for ideas on how to make writing fun and inspire your students to take chances and get a little silly.

The Role of Fun and Games in Writing

I am a game player. Scrabble. Board games. Music games. Puzzle video games. And that game mindset frequently seeps into my writing mindset. (Or maybe it’s the other way around.)

I presented about introducing elements of games into writing recently at NCTE in Baltimore. I specifically discussed poetry, though I think the mindset of adventure and games can be used in many areas of writing.

As a former eighth-grade English teacher, I realize that you have SO MUCH to fit into so little time. But with my own writing and on author visits, I find these techniques produce riskier, deeper, wilder, more creative work. Maybe you’ll find something here you can implement with your own students.

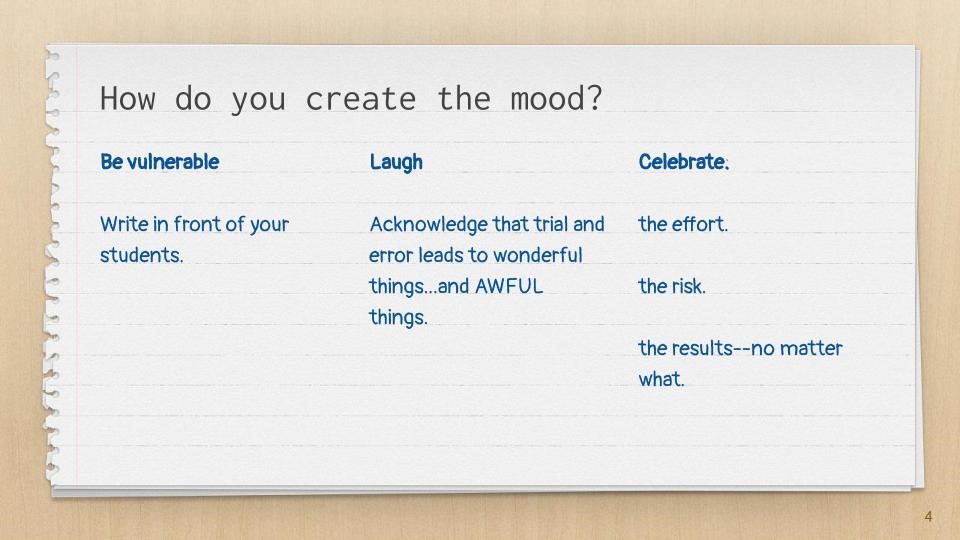

Mindset for the Writing

Creating the right mood is key.

When I start a first draft, my goal is to produce…something. Not something great. That’s too much pressure. Just something. Many of my first drafts are absolutely wretched. But I put that out of my head and remind myself of my goal. I accept (indeed, expect) that those words might be terrible. I try to laugh if ludicrous trash—or, worse, deadly dull writing—emerges. And I give myself buckets of gold stars just for showing up and doing the work.

In writing with students, I work to create the same atmosphere of risk and acceptance. I write poems in front of them, which is very intimidating. We write group poems together. I say upfront that sometimes the group poems rock, and sometimes they don’t. “But that’s okay,” I tell them. “It’s all about trying something and THEN seeing whether it worked or not.” I encourage them not to worry about whether they have the perfect word or line. And I draw clear boundaries on the way we react to each others’ efforts—always with a sense of shared community and the knowledge that sometimes the wackiest ideas turn out to be the creative heart of the poem. We celebrate our results, because we tried and we made something. My number one goal is to make kids feel like writers. I want them to know this basic truth: Writers don’t always write well. They write anyway.

Tools for the Writing Game

What tools arouse an adventurous writing spirit? One of my favorites is the phrase, “Let’s try something! Let’s…”

“Let’s try an I Made a Mistake poem!” I’ll say. I share an example:

I went to the bathroom to brush my hair.

I made a mistake…and brushed a bear.

Then I ask for a volunteer to name a place I can go (ha—politely, of course!), and I make a couplet. Then I start asking for both a place and a thing to do there. Before I know it, the kids are falling over themselves wanting to finish the couplet themselves. Or stumping me with a word that can’t be rhymed. We laugh, have fun with words, and don’t worry about being right.

Or I might say, “Let’s try something. Let’s write a poem backwards!” Or “Let’s come up with as many synonyms for ‘big’ as we can.”

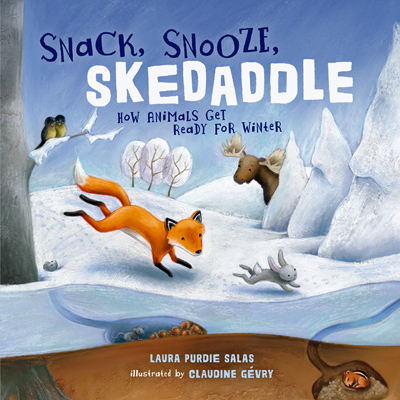

I use the “Let’s try something” trick on myself too. Because a lot of creative writing, for me, comes down to trial and error. My most recent book, Snack, Snooze, Skedaddle: How Animals Get Ready for Winter (illus Claudine Gévry, Millbrook Press) uses rhyming couplets to show how twelve different animals act BEFORE winter and then DURING winter.

I use the “Let’s try something” trick on myself too. Because a lot of creative writing, for me, comes down to trial and error. My most recent book, Snack, Snooze, Skedaddle: How Animals Get Ready for Winter (illus Claudine Gévry, Millbrook Press) uses rhyming couplets to show how twelve different animals act BEFORE winter and then DURING winter.

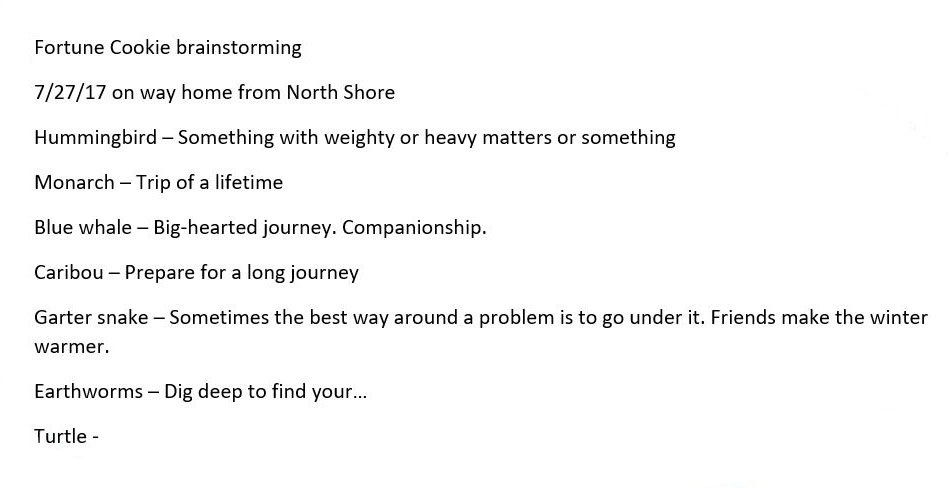

But that wasn’t my first approach. I thought, “Let’s try fortune cookies!” The monarch butterfly could read, “You’re about to take the trip of a lifetime.” Genius! But I couldn’t make it work.

Still, it was worth a try. So was my idea to have the animals share their winter break stories in a school play, which also didn’t pan out.

Still, it was worth a try. So was my idea to have the animals share their winter break stories in a school play, which also didn’t pan out.

The key to “Let’s try something” is that by using the word “try,” I’m acknowledging that I might fail, and that that’s just part of the process.

Other favorite tools insert randomness into a writing project. Use dice to decide how many lines a poem will have. Or how many facts a paragraph needs to share. Have kids draw a random word ticket out of a bag and write about it. Spin a globe and put your finger on it to find a place to write about. Use the name of a paint color or nail polish as a title for a story.

Other favorite tools insert randomness into a writing project. Use dice to decide how many lines a poem will have. Or how many facts a paragraph needs to share. Have kids draw a random word ticket out of a bag and write about it. Spin a globe and put your finger on it to find a place to write about. Use the name of a paint color or nail polish as a title for a story.

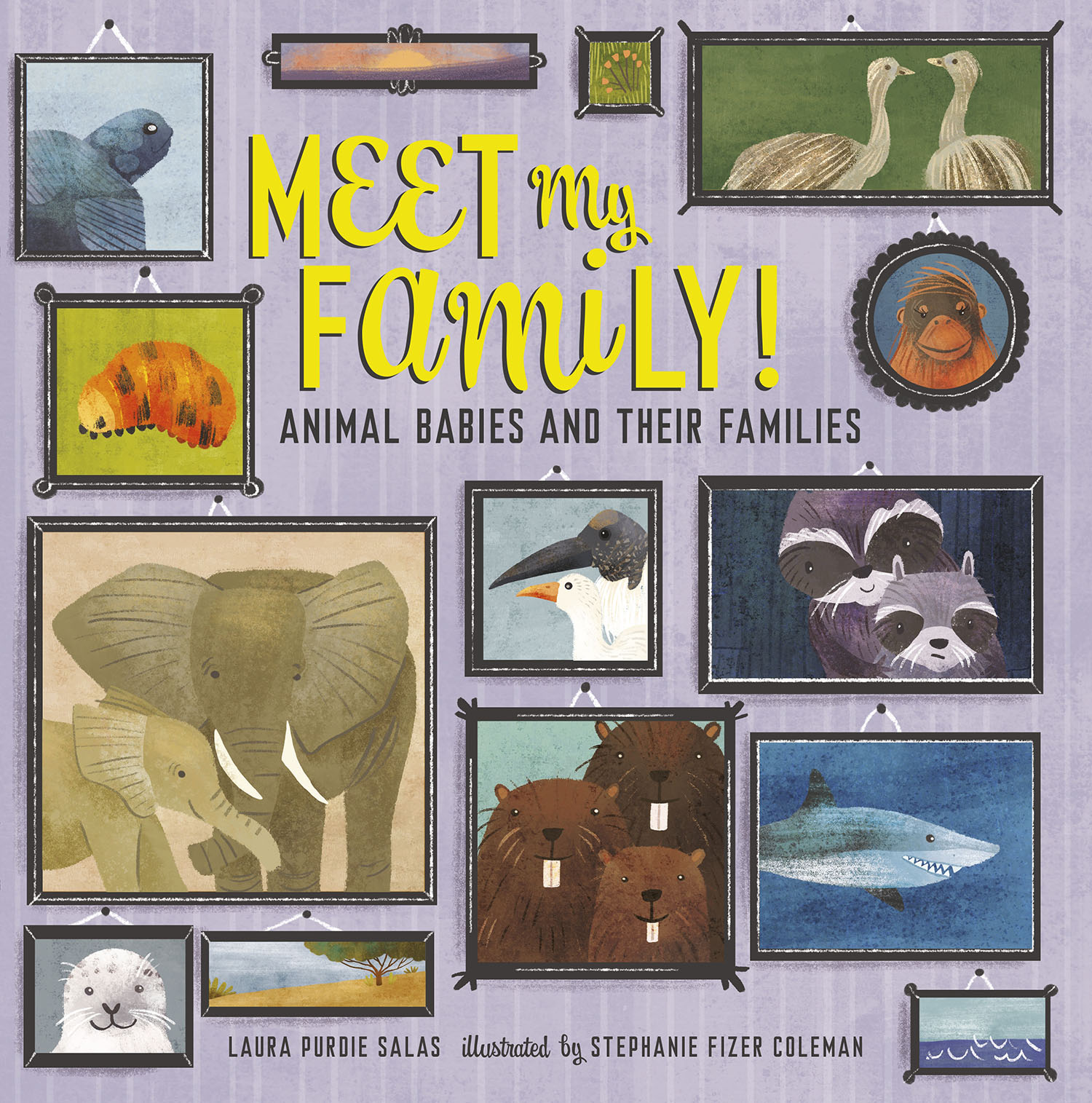

Or set a timer. I often set a goal for myself to brainstorm twenty possible titles for a manuscript in five minutes. Here’s a bit of a timed brainstorming for titles for what eventually became Meet My Family! Animal Babies and Their Families (illus Stephanie Fizer Coleman, Millbrook Press).

A short-timer takes the pressure off. It sets the bar low because who could write a masterpiece in five minutes? After a couple of speed-round poems with kids, they are in the groove. I explain the writing prompt, tell them the time limit, and say, “Ready, set, write!” Total silence follows, except for the sound of scratching pencils. Sublime.

It’s Not Whether you Win or Lose…

The final step is celebrating the process. I have loads of unpublished manuscripts seeking homes. Currently, they are, commercially, failures. But I love those manuscripts, and I celebrate every last draft. I showed up. I explored. I wrote.

I try to celebrate the same thing with students. Maybe a child’s poem is not stellar overall. But I can always find something to praise, something they have done well. Maybe it’s the smallest poem anyone wrote. The silliest poem. The poem with the most alliteration I’ve ever seen in my whole life.

On graded pieces of writing, students won’t always get an A. But I believe using some of these playful strategies can help every student see himself or herself as a writer. And that’s the very first step to becoming a better writer.