Some scary issues today have children asking many questions. Older students can find much in the way of explanation, but the problem is how to explain these issues to younger kids. Today we welcome Anastasia Higginbotham to Mackin Books in Bloom to talk about her latest book, Not My Idea: A Book about Whiteness, in which she explains the problem of racism in a way that even the very young can understand.

Check back here tomorrow to enter a contest for a copy of Not My Idea: A Book about Whiteness.

_________________________________________________________________________

I’m always scared when I introduce one of my books to a new group of kids. What if they’re mad at me for telling them the world is screwed up? What if they’re happily going along enjoying family life, school and gymnastics classes, and here I come, telling them everything’s wrong?

My new children’s picture book is about racism and white supremacy. I put a burning cross on the cover.

My new children’s picture book is about racism and white supremacy. I put a burning cross on the cover.

It feels like that cross has been burning inside my own chest since grade school, stabbed into the ground of my imagination. I didn’t put it there and neither did my mom and dad. But there it stands, shame billowing out in plumes. You can imagine my relief at getting it out onto the page. But when my publisher began planning the book tour, I got a serious case of the jitters.

I worried: What if when I read my book to kids, they stare back at me in horror, like I am the one who lit the cross and planted it inside them? Will black and brown kids feel condescended to—“Who is this white woman coming to my classroom to tell me about something I already know and I’m eight?” Will white kids giggle and pretend not to care? Will Indigenous kids and kids who are neither white nor black feel invisible and ignored by this book and this conversation?

It sounds counterintuitive to get to the heart of racism by giving even more attention to white people. And yet, so long as we continue to not know we’re white, not want to admit it, refuse to be associated with it, or flat-out deny that we’re hurting people with it, white supremacy will keep on winning. It will keep killing, stealing, lying, and burning inside the imaginations of kids who would never consent to such a stupid, violent idea as this.

Photo by Ellen Neipris

To prepare for the launch of Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness, I brought it to a workshop for kids and parents at PS. 261, an elementary school in Brooklyn facilitated by The Human Root Co-founder and Executive Director Anyanwu Uwa, who had been working with staff, students, and parents all year. Anyanwu facilitated an activity that cast away my fears about discussing whiteness with children of many races and socioeconomic backgrounds. Kids sat taller in their seats after reading the book. I saw them lean in. I saw intense focus on their faces and in their furrowed brows as they described how the book had affected them.

The experience confirmed that four things I had sensed were true, were true:

- Kids appreciate being trusted with important and dangerous information.

- Kids appreciate a chance to challenge adults on the subjects we try to hide from them.

- Kids need practice and support to connect their emotions and bodily truths (uh-oh feelings, knotted guts, bad sleeps, bouncy knees, tight chests) into coherent ideas and choices.

- Kids need help aligning what they know with who they are.

These kids were white, brown, black, Asian, Indian, cis gendered and gender nonconforming. They were in fifth grade. The adults sitting with them in their groups, listening and following along, were not their parents—they were parents who had opted into this workshop. This was an intentional choice by Anyanwu and the school’s principal, also a black woman.

These kids were white, brown, black, Asian, Indian, cis gendered and gender nonconforming. They were in fifth grade. The adults sitting with them in their groups, listening and following along, were not their parents—they were parents who had opted into this workshop. This was an intentional choice by Anyanwu and the school’s principal, also a black woman.

The way I read it, pairing children with adults who were not their adults lowered the emotional stakes while raising the expectation that the adults would see the children as human beings. It positioned the children to take up more space as representatives of childhood itself, nobody’s little anything (sweetheart, troublemaker, brainiac, champion).

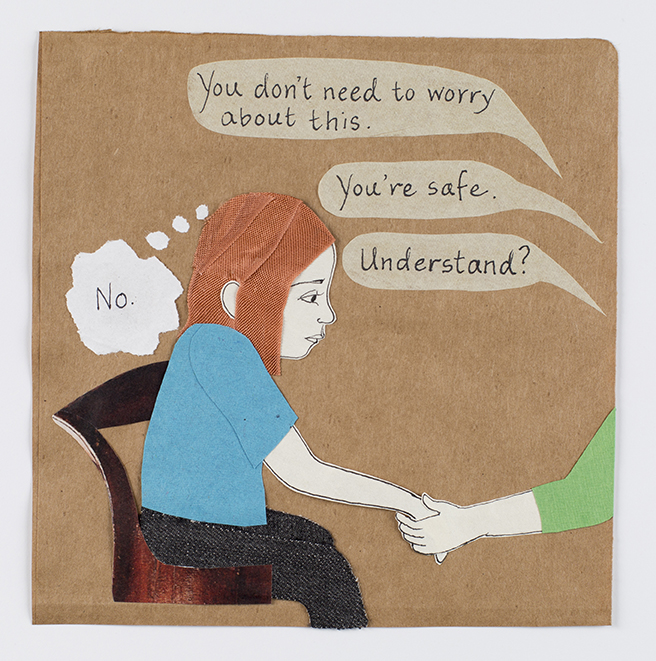

Among other things, students shared how they feel when they see their parents upset or crying. They spoke about how it feels when adults try to keep you from knowing a painful truth, but this actually makes you worry about your parents instead.

What will happen when they find out I already know …and, yeah, I am frightened and upset?

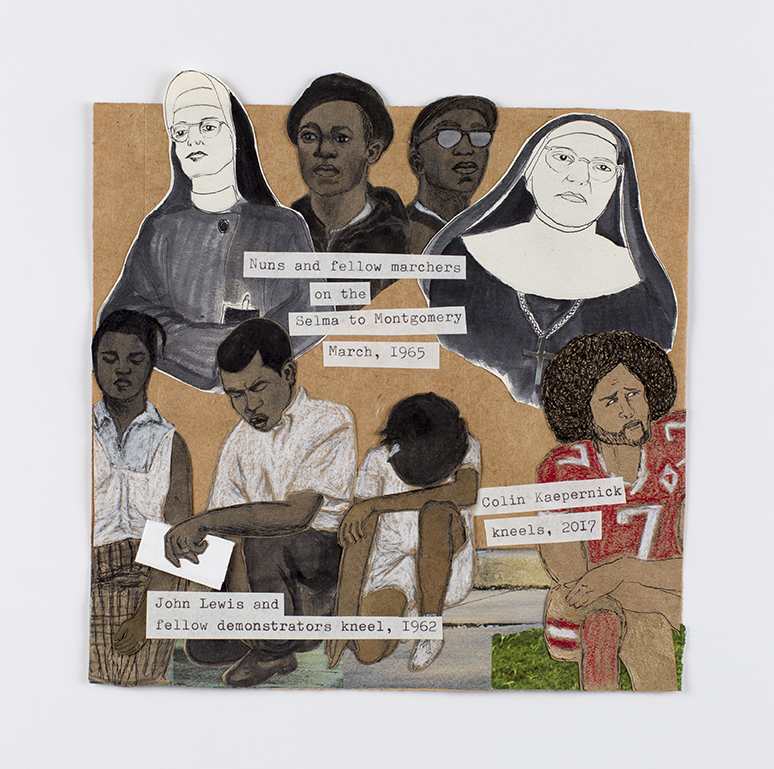

Since that trial run, I’ve read the book in libraries, schools, and bookstores in a dozen places—and I have dozens more to go during my fall book tour. At these reading, little kids want to sit right up with me, next to the cardboard cut-out of Colin Kaepernick (a life-size rendition of a page in the book) I made and take on tour with me. Sometimes after I read, we make collage out of scraps of paper and magazines—the same materials I use to make my books’ illustrations—to demonstrate that we already have the tools we need to make meaning and beauty out of what’s broken.

Since that trial run, I’ve read the book in libraries, schools, and bookstores in a dozen places—and I have dozens more to go during my fall book tour. At these reading, little kids want to sit right up with me, next to the cardboard cut-out of Colin Kaepernick (a life-size rendition of a page in the book) I made and take on tour with me. Sometimes after I read, we make collage out of scraps of paper and magazines—the same materials I use to make my books’ illustrations—to demonstrate that we already have the tools we need to make meaning and beauty out of what’s broken.

At age nine, my white niece Francesca asked what all my books would be about. We were sitting under an umbrella, eating strawberry Twizzlers and cheese puffs, poolside in a Raleigh suburb. She’d already read the divorce book, which came out the year her own parents split up; she knew it was the first in a series.

Next is death, I told her. After that, I’m making a book about the confusing messages about sex that tell you it’s both shameful and beautiful. After that, white supremacy. Then I’ll do family sexual abuse, followed by being the target of violence at your school because they suspect you’re gay and you might be. Oh yeah, and life-threatening asthma caused by environmental neglect and racism.

Next is death, I told her. After that, I’m making a book about the confusing messages about sex that tell you it’s both shameful and beautiful. After that, white supremacy. Then I’ll do family sexual abuse, followed by being the target of violence at your school because they suspect you’re gay and you might be. Oh yeah, and life-threatening asthma caused by environmental neglect and racism.

When I finished talking, I felt the urge to apologize to her for every word that had come out of my mouth. And I told her so.

“Hey, don’t worry about me,” she said, as kids splashed and floated past us. “I need to know what I need to know.”

Written by Anastasia Higginbotham:

Not My Idea : A Book About Whiteness. 9781948340007. 2018. Gr 4-6.

Tell Me About Sex, Grandma. 9781558614192. 2017. Gr 3-5.

Death Is Stupid. 9781558619258. 2016. Gr K-2.

Divorce Is the Worst. 9781558618800. 2015. Gr K-2.

_________________________________________________________________________

Photo by Drew Stevens

Anastasia Higginbotham is the creator of the Ordinary Terrible Things children’s book series which includes Divorce Is the Worst, Death Is Stupid, and Tell Me About Sex, Grandma, as well as Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness (www.DottirPress.com ), 2018). Higginbotham makes her books by hand in collage on grocery bag paper, using recycled materials, including jewelry and fabric. She offers talks and workshops about making meaning and collage out of ordinary, terrible childhood experiences.