We have been hearing a lot of debate about the Constitution lately—what the original writers meant, what it means for us today.

This blogger remembers learning about the Constitution in history class as a sophomore in high school (ages ago!). And what I remember most is the impression that, while the framers had a few mild disagreements about what should be in the document, they easily hammered out the details and wrote these rules for our country which, except for a few instances throughout history, have been our guiding rock ever since. As they will forever and ever. Amen.

It took me years (decades!) to realize that this rosy picture is not what really happened—which is why I am so grateful for Fault Lines in the Constitution by Cynthia and Sanford Levinson. And while the book was written for middle schoolers, I would have been well served by it as a high school sophomore—as I was as an adult reader, too!

Read on to hear the authors explain why and how they wrote this book. They have also written a discussion guide for educators, which includes suggestions for classroom and library activities and events.

_________________________________________________________________________

Marie and Pierre Curie won the Nobel Prize for Physics. Edith and Woodrow Wilson ran the country. Cynthia and Sanford (Sandy) wrote about the Constitution?

Marie and Pierre Curie won the Nobel Prize for Physics. Edith and Woodrow Wilson ran the country. Cynthia and Sanford (Sandy) wrote about the Constitution?

Well, we might not be quite as famous as the first two duos. But, like them, we have our own backstories, which led us to work together to create Fault Lines in the Constitution. And in our book, we share eighteen stories, each of which presents a fault line in the Constitution. Each was also a challenge to tell because we had to figure out together how to convey all of these problems with our country’s founding document, describe what happened at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 that led to them, explain how the problems relate to issues today, and summarize what states and other countries do to avoid them. After lots of discussions, we managed to do all of this in a single voice, except for the last chapter where we got into a ripping debate. How did this happen?

Behind the scenes, Sandy is a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin and, for the past fifteen years, at the Harvard Law School. He has written many books for law students, legal scholars, and the general public on the Constitution, public monuments, diversity, the Second Amendment, torture, and many other important and timely topics. He frequently writes and publishes with his friends and colleagues. You can tell from his titles—Our Undemocratic Constitution, Constitutional Stupidities, Constitutional Tragedies, and Framed: America’s 51 Constitutions and the Crisis of Governance—that several of these books, along with a number of articles and blog posts, argue that the US Constitution does not serve America well.

Behind the scenes, Sandy is a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin and, for the past fifteen years, at the Harvard Law School. He has written many books for law students, legal scholars, and the general public on the Constitution, public monuments, diversity, the Second Amendment, torture, and many other important and timely topics. He frequently writes and publishes with his friends and colleagues. You can tell from his titles—Our Undemocratic Constitution, Constitutional Stupidities, Constitutional Tragedies, and Framed: America’s 51 Constitutions and the Crisis of Governance—that several of these books, along with a number of articles and blog posts, argue that the US Constitution does not serve America well.

Cynthia used to teach pre-K, kindergarten, middle school, high school, General Education Development (GED) for adults studying for high school diplomas, and teachers-in-training. After that, she worked in state-level educational policy development and, about ten years ago, started writing nonfiction articles and books for young readers. She had never written a word with another author.

Then, Cynthia’s editor at Peachtree Publishers, Kathy Landwehr, who had seen some of Sandy’s books and knew his views of the Constitution, asked us if we’d write a book together for kids. Of course, we would! Cynthia figured all she had to do was read Sandy’s books more closely than she had before and reword them for ten- to fourteen-year-olds. Easy peazy. Until she realized that law-talk does not readily translate into kid-speak.

For instance, the following partial sentence from Our Undemocratic Constitution is cogently phrased for an adult audience: “Significant distortions and outright failures of American politics are produced because of—and not merely in spite of—the structure of the government imposed by the Constitution…” And the example he gives of Alaska’s pork-barrel Bridge to Nowhere convincingly illuminates for grown-up readers his point that the fact that every state gets two senators, regardless of the size of its population, produces an undemocratic legislative process and inequitable outcomes for citizens.

Cynthia’s task was to make this point not only comprehensible but also appealing to a younger set. So, rather than describe legislation about a bridge, we tell a story in Fault Lines about why soft drinks, cereal, and muffins are loaded with corn syrup. The reason is similar to the Alaska situation: four or five rural, corn-growing states in the Midwest get the same number of senators as four or five highly populated, urbanized states, and the small-state senators can hold up a lot of laws needed by cities until they get corn subsidies and price supports for the farmers back home.

Cynthia’s task was to make this point not only comprehensible but also appealing to a younger set. So, rather than describe legislation about a bridge, we tell a story in Fault Lines about why soft drinks, cereal, and muffins are loaded with corn syrup. The reason is similar to the Alaska situation: four or five rural, corn-growing states in the Midwest get the same number of senators as four or five highly populated, urbanized states, and the small-state senators can hold up a lot of laws needed by cities until they get corn subsidies and price supports for the farmers back home.

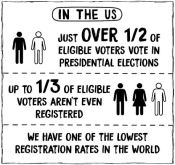

An image in our book makes the point starkly. The circle graph displays how, in 2016, “half the US population was represented by 18 senators; the other half was represented by 82 senators.” Shocking, isn’t it?

Repurposing Professor Levinson for the upper middle-grade through high-school set does not mean that we diluted him into Sandy Lite. We worked out ways to explain complicated concepts, including proportional representation, the history and mathematics of gerrymandering, and the meaning of the Latin phrase habeas corpus. We did these by telling dramatic stories (Ebola!), breaking big issues down into consumable bites, bringing the Framers’ arguments from 230 years ago to life today, and explaining how decision-making is done differently in other countries.

The process wasn’t quite as neat as it sounds, though. There were times we changed our minds. The chapter on the filibuster, for instance, was in the book, then out, in, out, in. There were times that our editor changed our minds, such as when she pointed out that the moving story about a fugitive slave named Anthony Burns just didn’t belong. It was a great introduction—but not to this book.

There were times, furthermore, when we, the coauthors, had to change each other’s minds. Sandy needed to convince Cynthia that the section on Inauguration Day, which comes over two months after Election Day, was a significant enough fault line to include. We were both lobbied by our son-in-law to highlight the fact that Washington, DC, does not have voting representation in Congress—an injustice that most of America pay little attention to.

There were times, furthermore, when we, the coauthors, had to change each other’s minds. Sandy needed to convince Cynthia that the section on Inauguration Day, which comes over two months after Election Day, was a significant enough fault line to include. We were both lobbied by our son-in-law to highlight the fact that Washington, DC, does not have voting representation in Congress—an injustice that most of America pay little attention to.

And, there was the matter of our debate, when neither of us changed the other’s mind. Sandy firmly believes that our Constitution is so flawed that only a new Constitutional Convention can repair—actually, replace—it. Cynthia frets about the lack of direction that Article V of the Constitution gives for such a convention. How would delegates be chosen? What powers would they have? She prefers changing our founding document through amendments and legislation, slow as these processes are.

In the end, though, not only did we learn a tremendous amount from each other as we wrote the book, we also agree that it’s imperative for young people to know and speak up about the fault lines built into our Constitution before they slip asunder and cause a catastrophe to our democracy. And, as you’ve undoubtedly figured out, Fault Lines needed not only a duo but also a supportive army of researchers, artists, family members, and editors.

Also for K-12 by Cynthia Levinson:

Hillary Rodham Clinton : Do All the Good You Can. 9780062387301. 2016. Gr 4-6.

Watch Out for Flying Kids: How Two Circuses, Two Countries, and Nine Kids Confront Conflict and Build Community. 9781561458219. 2015. Gr 6-8.

We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March. 9781561456277. 2012. Gr 5-8.

The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a Young Civil Rights Activist. 9781481400701. 2017. Gr K-4.

________________________________________________________________

From the publisher:

Sanford Levinson has been on the faculty of the University of Texas Law School since 1980 and a member as well of the Government Department at the University of Texas, Austin since 1984. He had previously taught at Ohio State and Princeton. The author or editor of 15 books on the Constitution and other related topics, Levinson, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Law and Courts section of the American Political Science Association in 2010. He has also written for a number of general magazines and newspapers, as well as contributing frequently to the blog Balkinization.

A former teacher and educational policy consultant and researcher, Cynthia Levinson holds degrees from Wellesley College and Harvard University. Her multi-award-winning nonfiction books for young readers include We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, Watch Out for Flying Kids: How Two Circuses, Two Countries, and Nine Kids Confront Conflict and Build Community, Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws that Affect Us Today, and The Youngest Marcher: The Story of Audrey Faye Hendricks, a Young Civil Rights Activist.