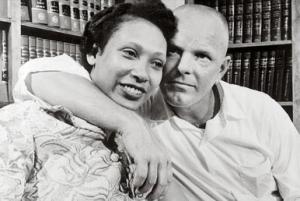

In June of 1958, Virginians Richard Loving (a white man) and his bride-to-be Mildred Jeter (a black woman) went to Washington, D.C. to be married. The reason? Interracial marriage in the state of Virginia was a crime.

In June of 1958, Virginians Richard Loving (a white man) and his bride-to-be Mildred Jeter (a black woman) went to Washington, D.C. to be married. The reason? Interracial marriage in the state of Virginia was a crime.

After returning to their Virginia home as Mr. & Mrs. Loving, the couple was arrested during the early morning hours of July 11, 1958. Despite their marriage certificate, they were charged with breaking the law and sentenced to one year in prison unless they left the state and never returned as a couple. The protracted legal battle that followed eventually landed in the United States Supreme Court.

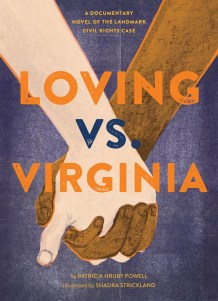

Earlier this year, author Patricia Hruby Powell and illustrator Shadra Strickland teamed up to create Loving vs. Virginia: A Documentary Novel of The Landmark Civil Rights Case. We were fortunate to nab an interview—facilitated by the book’s editor, Melissa Manlove—about the process that went into creating the novel:

MELISSA (Editor): The idea of a book for teenagers about the Supreme Court case Loving vs Virginia came from my Publishing Director, Ginee Seo. But that was all we had of the idea at that point—we didn’t know whether the book would be fiction or nonfiction, prose or poetry, or really any idea of what shape it would take. That would be up to the author. I don’t remember how I first mentioned it to you, Patricia, or when we started using the term “documentary novel”. Do you remember how we started ou

MELISSA (Editor): The idea of a book for teenagers about the Supreme Court case Loving vs Virginia came from my Publishing Director, Ginee Seo. But that was all we had of the idea at that point—we didn’t know whether the book would be fiction or nonfiction, prose or poetry, or really any idea of what shape it would take. That would be up to the author. I don’t remember how I first mentioned it to you, Patricia, or when we started using the term “documentary novel”. Do you remember how we started ou

PATRICIA (Author): I started writing Loving vs. Virginia as nonfiction. I’d been interviewing Mildred’s brother, Lewis Jeter, by phone. He was telling me about the black, white, and Native American neighbors of Central Point helping each other at harvest time and having parties to celebrate those harvests; about how he and his siblings attended the one room school; about their big brothers Otha and James and the others being friends with Richard Loving; about how Sheriff Garnet Brooks was universally detested for his racism. I gave you an outline and the first three non-fiction chapters, telling how they lived in the neighborhood.

You called me—I happened to have been in the Philadelphia Airport—and asked if I’d consider writing it as a ‘documentary novel.’ I was invested in this fascinating, heart-wrenching story, so I said, “Sure, what’s a documentary novel?”

MELISSA: A documentary novel presents a very lightly fictionalized historical narrative, sometimes with supporting materials like photos, newspaper articles, etc. Its goal is always to portray history accurately, but also to personalize it.

MELISSA: A documentary novel presents a very lightly fictionalized historical narrative, sometimes with supporting materials like photos, newspaper articles, etc. Its goal is always to portray history accurately, but also to personalize it.

PATRICIA: In a documentary novel I would be able to write in the voices of the characters—my choice of whom. Clearly I would have to write from Mildred’s and Richard’s points of view. I also tried out scenes in the voice of their friend Ray Green, but we deleted Ray’s voice early on because the couple could speak for him. The documentary novel form was a gift. Now I could make arced scenes and show their lives—draw readers in to the deep emotion of their lives.

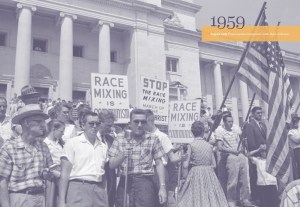

MELISSA: I remember both of us thought a lot about how to engage today’s teens—to whom the events of even the 1990s are historical—and effectively bring across what the 1950s and 60s were like. So you wrote sections into the book that were pure nonfiction, that would let you tell the reader—in quotations and photographs from the time, and in commentary—about the wider civil rights struggles of school integration, the desegregation of buses, libraries, lunch counters; how volatile the country was, and how virulent the hatred Mildred and Richard’s cause faced. You did a huge amount of research.

PATRICIA: I listened to both Mildred and Richard speak on newsreel footage and in Hope Ryden’s 12mm footage taken in the early 1960s. Mildred was soft-spoken, gentle, lyrical and poetic. Richard was also soft-spoken but with an edge to his voice—a defensiveness. It was a pleasure to establish my version of their voices. I also like the idea of writing for teens in succinct verse. There’s a lot of white space on the page; it reads easily. There’s no waste.

MELISSA: So we had a really strong draft of the book. But there was still more work to do to make these two people real and deeply empathize-able to our teen readers. Some of that you accomplished in expanding on their romance in the text, Patricia, but I wanted images of them as teenagers, and there were simply no photographs at all of Richard and Mildred as young people.

That’s when we turned to Shadra. Jennifer Tolo Pierce, the book’s brilliant designer, had seen some loose pen-and-ink work that Shadra had posted from a vacation.

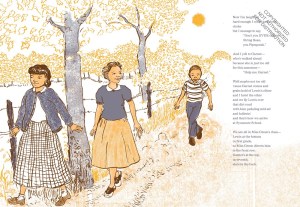

SHADRA (Illustrator): I always wanted to work in the 1950s “visual journalism” style for a book, but thought I might never get the chance to do so in a book for young people. My agent loved the visual journalism drawings I had been sharing with her and decided to put them up on our website to see what would happen.

SHADRA (Illustrator): I always wanted to work in the 1950s “visual journalism” style for a book, but thought I might never get the chance to do so in a book for young people. My agent loved the visual journalism drawings I had been sharing with her and decided to put them up on our website to see what would happen.

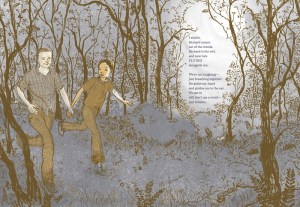

That’s where Jennifer saw them, and I was asked to contribute to the book. I was intrigued to try my hand at making drawings that looked like they were done on the spot, by a witness to these events. I was nervous because the drawings Jennifer saw on my website were done without any preliminary sketches or studies. When I asked Jennifer and Melissa if they would mind if I just made all of the drawings without sketches to retain the freshness of the art, they both agreed as long as I could make changes if needed.

MELISSA: The spontaneous quality of Shadra’s art and her tender renderings of Richard and Mildred and their home gave the look of the book a more personal feel, and that was important—both to make the book more accessible to teenagers and also to underline the human heart of this story.

PATRICIA: You did a bunch of research, too, Shadra.

SHADRA: I watched the same footage as you, to get a sense of Richard and Mildred in their youth. I also pored over the photography of Grey Villet to get a sense of the couple. Lastly, I sourced a few pics from my mother’s childhood growing up in Georgia. So many of the experiences that Mildred had growing up were similar to stories that I heard from my mom and her siblings.

SHADRA: I watched the same footage as you, to get a sense of Richard and Mildred in their youth. I also pored over the photography of Grey Villet to get a sense of the couple. Lastly, I sourced a few pics from my mother’s childhood growing up in Georgia. So many of the experiences that Mildred had growing up were similar to stories that I heard from my mom and her siblings.

MELISSA: That sense of family comes across in your art. I think it’s easy to expect that the people behind a landmark case like this will be crusaders, bigger than life. But the brilliant thing about Richard and Mildred’s story is that they weren’t—they were just humble country people who wanted to live as a family, and who wanted to go home.

The informal, first-hand feeling of Patricia’s text and Shadra’s art places the reader in the lives of Richard and Mildred Loving. We hope that teenagers will see in this story the truth that history is not a textbook—history is people, and their pains and their triumphs are never very far from us.

Thanks again to Patricia, Shadra, & Melissa for providing Books in Bloom with those fantastic insights into the creative process behind Loving vs. Virginia. For further interest, check out the 2016 film “Loving”…

Patricia Hruby Powell (Author)

Shadra Strickland (Illustrator)