Mem Fox is one of the world’s most beloved picture book authors. Her masterful use of meter, rhyme, and rhythm endear her works to children and adults alike. She has been recognized with incredible honors from being named a Member of the Order of Australia to having a limited-edition collection of coins minted that depict characters from her first and most popular book, Possum Magic. Fox is a passionate literacy advocate, a champion for human rights, a highly sought-after speaker, and a devoted wife, mother, and grandmother. Here, she shares details about her life and work with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler.

Mem Fox is one of the world’s most beloved picture book authors. Her masterful use of meter, rhyme, and rhythm endear her works to children and adults alike. She has been recognized with incredible honors from being named a Member of the Order of Australia to having a limited-edition collection of coins minted that depict characters from her first and most popular book, Possum Magic. Fox is a passionate literacy advocate, a champion for human rights, a highly sought-after speaker, and a devoted wife, mother, and grandmother. Here, she shares details about her life and work with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler.

The Partridge Years

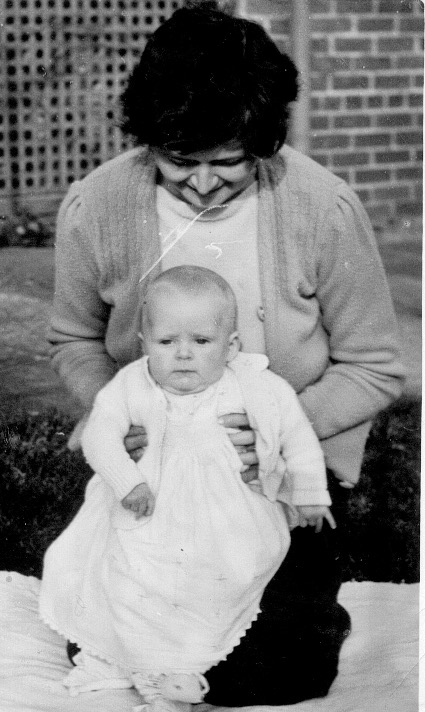

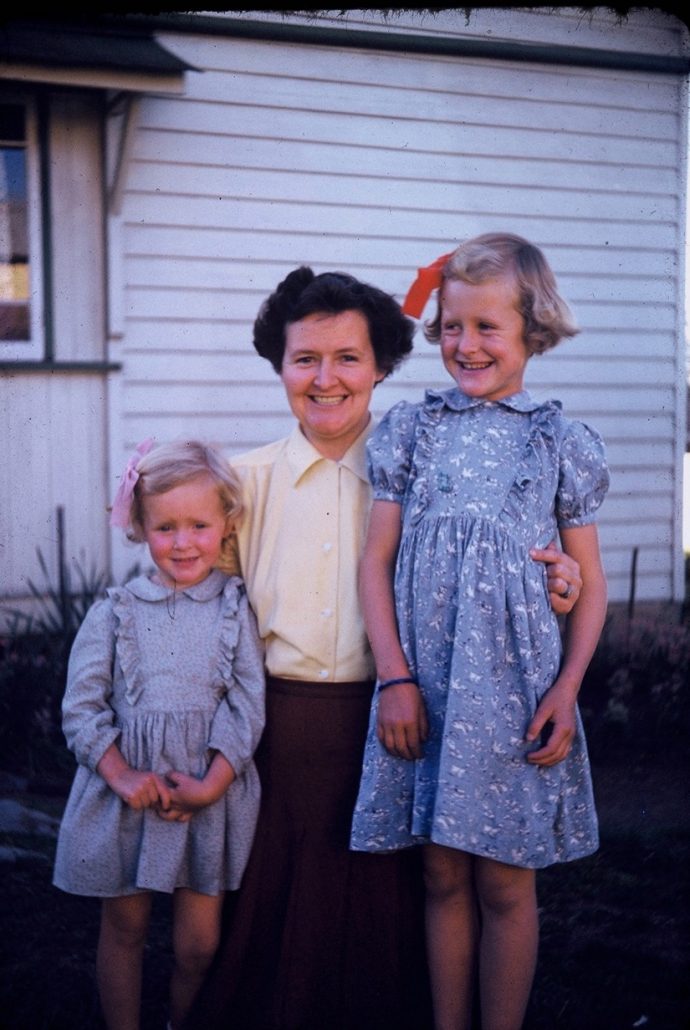

Fox and her mother, 1946

You are known today as Mem Fox, yet your given name at birth was Merrion Partridge. Why do we know you as Mem instead of Merrion?

“Merrion” is such an unusual name (I have never met anyone else with that name) that I had to explain its pronunciation and spelling every time I was asked. It was tedious. At age 14, I grew tired of the constant explaining and called myself Mem for short. The reason for that choice is now lost in the mists of time.

You were born in Australia but grew up in Africa as the child of a missionary family. What was your family’s purpose at the mission and was it part of your faith group?

My mother was Methodist. She came from a long line of Methodist ministers. The mission, Hope Fountain, was run by the London Missionary Society, which is Congregational. My father was the director of the teaching training school on the mission.

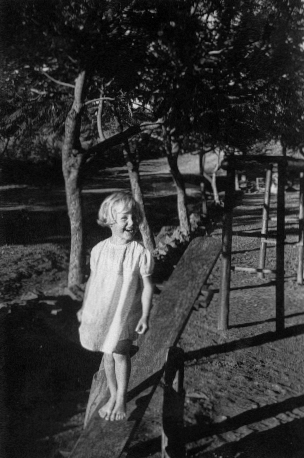

What was it like to grow up on a mission?

I loved growing up there. It was like growing up on a farm. We were free to roam all day long, from dawn to dusk, without our parents having any idea where we were. There were lots of African children, as well as the children of other missionaries, to hang about with. The mission was only 11 miles from Bulawayo, a major modern city, so it wasn’t exactly “wildest” Africa.

Even though you were close to a major city, your first year of education sounds a bit rustic. With no paper and pencils, you had to write in the dirt?

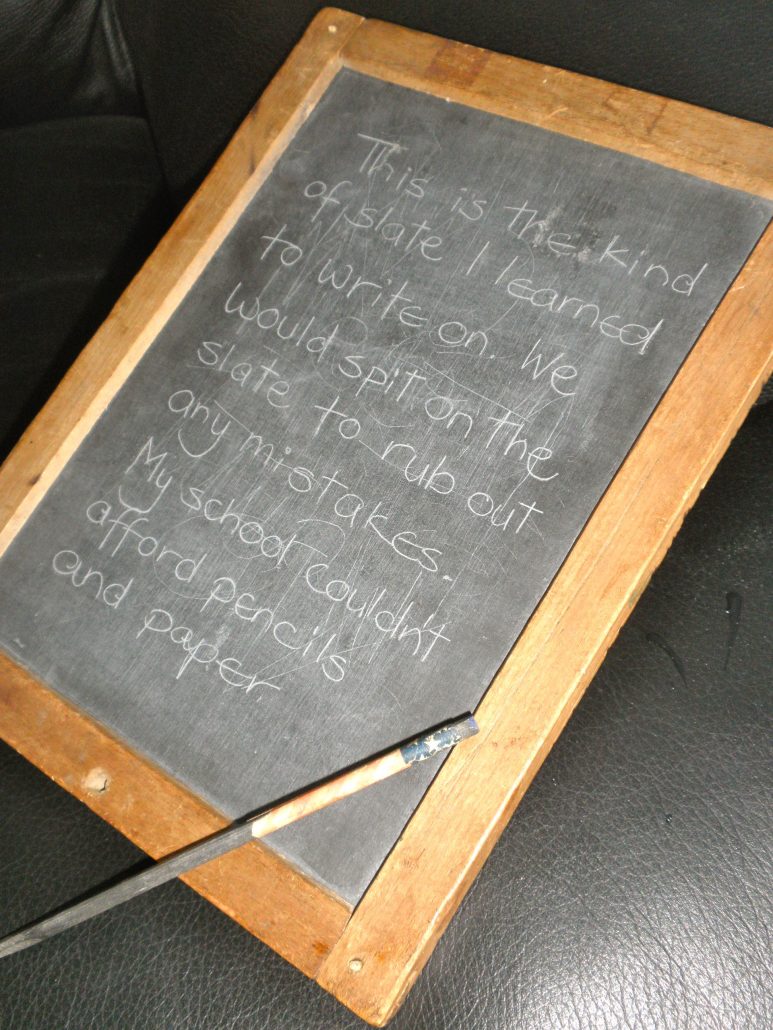

The slate Fox learned to write on

I had to write in the dirt for the first term of my schooling. After that we graduated proudly to slates and slate pencils.

After your first year of school, government authorities required you to attend an all-white school. Did you have the usual classroom supplies at your new school?

My white school, back in 1952, looked like any ‘typical’ school. In the African schools, also, children had all the normal accoutrements associated with schooling. It was just a case of getting to that stage more slowly so as not to squander scarce resources.

The Magic of Reading

So when did you learn your letters, numbers, and sight words?

I think I knew how to read before I started school. My dad was a highly gifted teacher, and I think he’d have seen to it that I not only loved books, but could read them myself as soon as possible.

“I strongly believe that the first five years at home should be about loving each other (parent and child) and loving sharing books—not about teaching reading.”

As an advocate for reading aloud to children, your parents must have read to you.

Indeed, they did. I recall Bible stories being very exciting and dramatic, and I loved stories about Australian animals and their dangerous existence in a hostile environment. I also recall the soothing nature of the togetherness of my sisters and mother as she read to us. It was the social warmth as much as the literature itself that I adored.

What are your first memories of reading yourself?

I have no recollection of not being able to read. I can’t recall my first memories of reading; but as a teenager, in the afternoons, I would lie on my bed lost in literature as wild thunderstorms battered the roof. I LOVED that feeling of being lost in another world as my world crashed around me.

Did you have a plentiful supply of books to enjoy?

My parents left Australia in 1946 with a veritable library. I was never at a loss for something to read. On our bookshelves there were vast numbers of poetry books, all of Dickens’ novels, most of the famous classic novels, children’s stories, encyclopedias, atlases, and books about Australia.

Do you remember favorite books or authors?

Do you remember favorite books or authors?

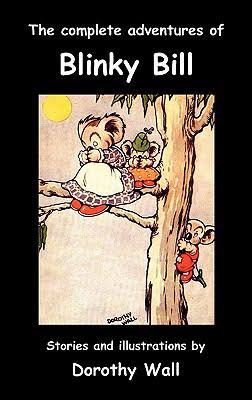

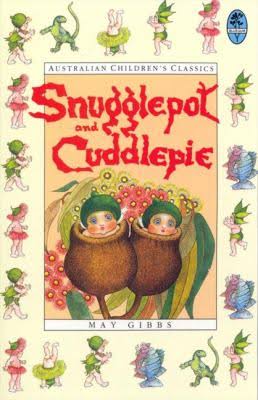

There were two classic, lengthy books from Australia that captured my imagination most: Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (Angus & Robertson, 1918) and Blinky Bill (Angus & Robertson, 1933). They were probably favorites because of their Australian-ness, but I also recall they were terrifying and thrilling and spared no thought for the tender emotions or terrors of young children. It was no-holds-barred drama on every page.

Clearly, reading is a passion of yours. What about writing?

I have always loved reading. I fear and loathe writing now that I know how impossibly difficult it is, but I loved it as a child. I wrote my first “book” when I was 10. I knew by 14 that I had a talent for writing.

Did your teachers encourage you to develop your writing skills?

At high school, I had the same brilliant English teacher year after year. She had enormous faith in my ability as a writer and was a huge encouragement to me, even after she died!

Despite your passion for reading and your talent for writing, when it came time for you to attend college, you did not choose to major in English. Instead, you chose to study drama. Why?

I was crazy about drama and starred in many school plays.

The Discovery of Purpose

Fox on her wedding day, 1969

Following college, where did life take you?

After college, I was a volunteer in Zimbabwe and Rwanda teaching English. I married Malcolm Fox in 1969, and we migrated to Australia in 1970. There, I taught English to migrant children in the evenings and drama in schools in the daytime. I taught drama for many years, until 1996, in schools first and then at a teachers college and university.

You are known worldwide as a passionate advocate for literacy. How did your interest and knowledge in this field come about?

In 1980, I took a year out to study the teaching of literacy: the college asked me to do it, for staffing reasons, and I was eager to accept the challenge.

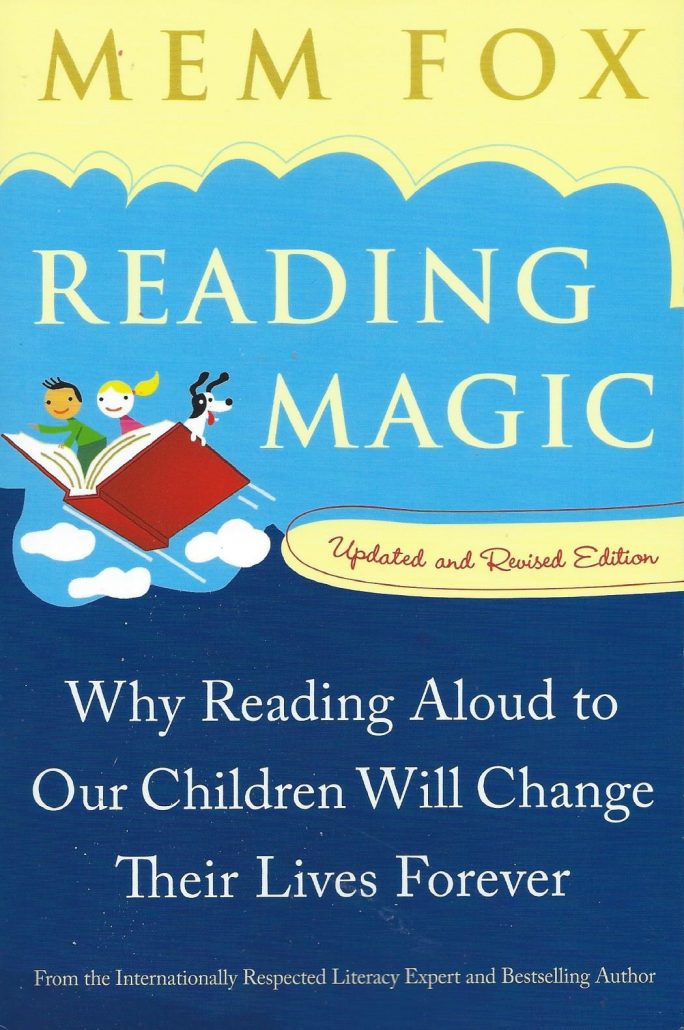

In your book, Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever (HMH, 2001), you discuss your ideas and insights about the power and importance of reading. How did you develop your theories?

In your book, Reading Magic: Why Reading Aloud to Our Children Will Change Their Lives Forever (HMH, 2001), you discuss your ideas and insights about the power and importance of reading. How did you develop your theories?

I was a university academic for 26 years, so the work in Reading Magic was not situational. It was based on solid research from around the world.

In a nutshell, what is your philosophy as shared in Reading Magic?

I strongly believe, along with millions of other caring professionals, that the first five years at home should be about loving each other (parent and child) and loving sharing books—not about teaching reading. However, once a child hits school, then phonics should be taught, absolutely, but not to the exclusion of the sense and sensibility of great literature, otherwise the words and sounds children learn and have no hooks to make meaning from, let alone create the joy and happiness that we want children to have in relation to reading. I am all for intense teaching. I would be horrified if it weren’t occurring. It’s the difference between reading at home, and learning to read at school that I emphasize. The first should be entirely joyful. The latter should be entirely joyful also, with the added element of superb, closely focused teaching.

You are a proponent for delaying formal education for children. Yet, with efforts to be competitive in the global marketplace, more and more officials are calling for structured early education. What are your thoughts on formal education for children as young as three years old?

Ghastly. It should never happen.

What about the STEM focus in education currently? As a literacy consultant, how do you feel about education zeroing in on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics?

What about the STEM focus in education currently? As a literacy consultant, how do you feel about education zeroing in on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics?

I am all for STEM. The future of the world depends upon it. But there is no STEM without literacy first.

In Reading Magic, you address the idea of reluctant readers, many of whom happen to be boys.

There are no reluctant readers who have found the right book! Most reluctant readers are reluctant because of the utter garbage they have had to suffer through their school readers, which are badly written, have no emotional content, and no other redeeming quality either.

So what can parents do to help their children connect with reading?

- Begin at birth.

- Never get tense around books or learning to read.

- Have a huge variety of reading material available for your child.

Do you have any advice for teachers?

Yes. Teachers shouldn’t forget that literature exists. They should read it with passion and regularity.

And what would be your advice for librarians?

Aha! Librarians need to recall that their main role used to be reading to children. It’s not about helping kids navigate the digital world. That’s so sterile, even though it’s necessary. It’s about introducing fabulous emotional experiences to children by reading them great books or suggesting great books if children are too old to be read to.

Fox in Turin, Italy receiving the Best Picture Book award at the Turin Book Fair 2010 for Ten Little Fingers and Ten Little Toes in the Italian edition. Photo by Maria Vernetti

The Far Reach of Influence

Fox with Julie Vivas, 2016

Speaking of great books, your writing career began with Possum Magic (Harcourt, 1983), which actually was an assignment when you returned to university for literature studies. It is hard to believe that nine publishers turned it down before it was finally accepted—and now it has sold well over 3 million copies and has received several awards. Possum Magic even has its own limited-edition coin collection which was introduced in August 2017. That is incredible!

No one can imagine the level of my excitement at the real magic that’s happened, thanks to the Royal Australian Mint and Woolworths, and in particular to the brilliant illustrator of the book, Julie Vivas, whose feet I kiss, and without whom I would never have become the well-known writer I am today. Julie worked hard on the design of the coins to maintain the integrity of the original art. As you can imagine, nothing could be more magical than turning Possum Magic from a book into a collection of coins. I’m dizzy with amazement, and honestly, overcome with gratitude that our beloved book is being immortalized in this way.

Clearly, this book and your subsequent picture books have deeply touched readers across Australia and throughout the world. What is it about picture books that draws in readers and moves them so deeply?

High quality picture books are adored by all ages as there is always something in them for adults, too. Even my university students loved picture books: the drama, the universal themes, the pictures, the soothing rhythms, the wild repetitions, and so on.

“Writing is so hard to do well and so easy to do badly.”

Do you believe there is ever a time to put picture books aside and pick up chapter books instead?

There is no right time to move on. We move from picture books into reading longer books when we are able to, and when we want to. As I’ve said, adults love picture books, so clearly they are a delight to come back to, post-childhood, as teachers, parents and librarians.

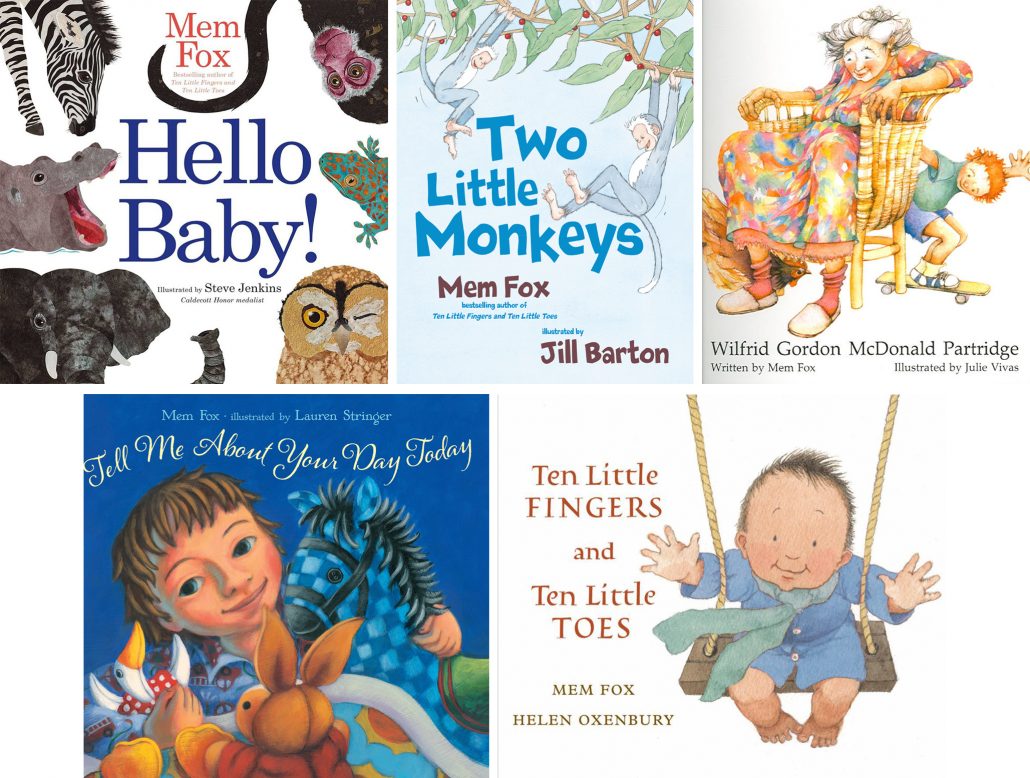

You are a master at writing picture books such as Tell Me About Your Day Today (Beach Lane Books, 2012), Two Little Monkeys (Beach Lane Books, 2012), and Ten Little Fingers and Ten Little Toes (HMH Books for Young Readers, 2008). The way you create rhythm and rhyme and weave them with heartwarming messages is unmatched like Hello Baby! (Beach Lane Books, 2009) and Wilfrid Gordon McDonald Partridge (Kane/Miller Book Publishers, 1995). How did you develop this writing style? Does it take work or do the words just flow? I thank God for having grown up on a mission with the perfect cadences of the King James edition of the Bible dripping into my veins; then for having gone to drama school and learning Shakespeare and the great poets by heart; and then for having a daughter to whom I read the magical rhythms of Dr. Seuss over and over again. These three influences gave me a unique insight into and a feeling for rhythm, which is, I believe, the main reason for my apparent success. No one wants to read an un-rhythmic book to a child.

Your success would seem to be a bit more than “apparent” based on the list on your website of awards and honors you have received.

I am surprised and thrilled every time I receive an honor, no matter from whom. I still see myself as some sort of impostor in the world of writing, and find it hard to believe that anyone would give me an award for any reason, although I do feel secretly ecstatic when it happens. I am filled with great gratitude for each one.

The Writing Process and Environment

You’ve written nearly 50 books over the past 35 years or so while teaching at the university, and traveling and speaking internationally. You must have a writing process in place that works well for you.

I write very rarely, perhaps a total of three weeks a year, in tiny bursts. My life is too full of other things to have time to write. Hah! That’s just an excuse for running away from my writing desk as fast and as often as I can because writing is so hard to do well and so easy to do badly.

Fox’s neat desk

You mentioned a desk. Do you have a dedicated writing area, then?

I have two writing areas. One is a desk in the bedroom where I handwrite manuscripts, letters, cards, and administration work. I also have a designated office in my house, which is my second writing area. It has the computer, scanner, files, stationery cupboards, phones, etc. I type in the office but never handwrite in it. They are very different spaces.

You handwrite manuscripts? Does that mean you write longhand with a pen or pencil?

I begin with a 4B pencil and paper. My brain works better that way because it’s slower and the choice of words is therefore more considered. Whenever I have a writing problem that I can’t solve, I move from my computer back to the pencil and paper. (4B pencils are very soft, so you don’t have to press hard. This avoids writer’s cramp.)

How do you write? Do you first have a theme or a moral or message you want to convey and then work to rhyme the text?

When I write, I write a story. I don’t think of a theme: the theme arises organically. And I hope I never have a moral. Children detest books with morals. And I never outline. My favorite writing maxim (I can’t remember who said it) is: “Why would I write if I knew what I were going to say?” We find out what we want to say by writing and rewriting. The rewriting can go on for years, even with a picture book of 500 words.

Do you have a set time for writing or a ritual beyond starting with a 4B pencil and paper? Do you read something first or listen to music or exercise or anything like that?

Never. Never! I can’t listen to music: when I write, I’m creating music myself, out of words. I do not exercise to get myself motivated to write, although I do go to a fitness class twice a week and have done so for 24 years.

Allyn Johnston (editor), Fox and Theo, 2011

What about collaboration. Do you work with others when creating your books?

My beloved editor Allyn Johnston (from California) comes to stay with me from time to time for ten days or so. At these times I work intensively with her, and we collaborate closely—almost reading each other’s mind. But typically, I work totally alone in dead quiet. I collaborate with my illustrators very rarely. I like to give them space to do their own thing.

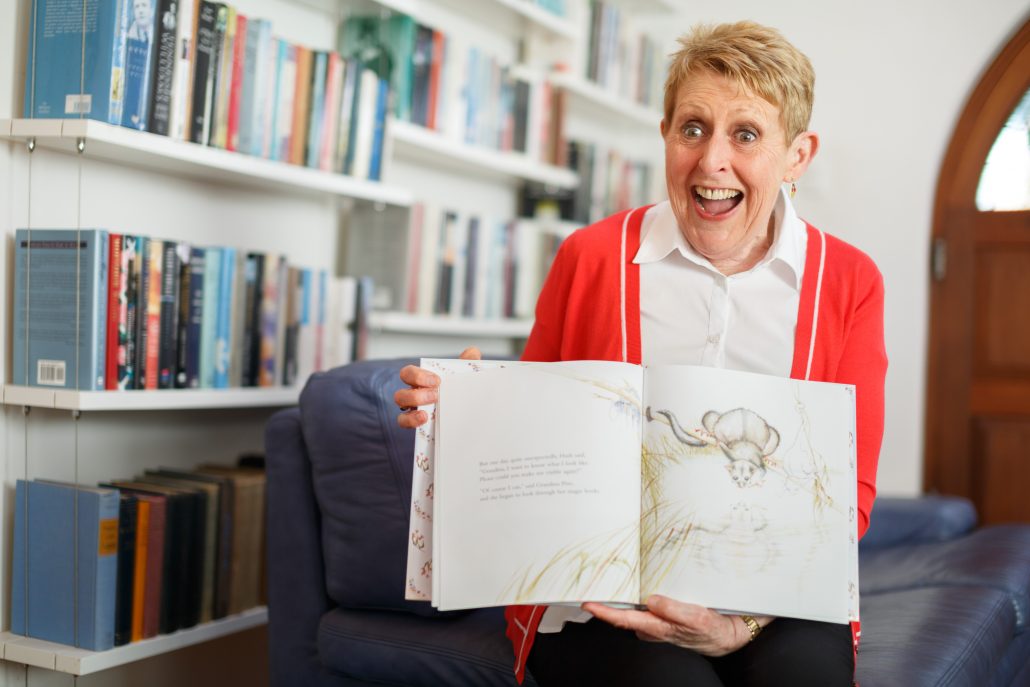

Fox reading to her grandson, Theo

What does an “average” day look like for you if there is such a thing?

No day is the same, and no day is average. My grandson is seven and he spends most of his after-school hours with us. We also see him at the weekend, both days. I mourn the days I’m away from him. I answer endless emails every single day, with grinding teeth. I cook meals with care and devotion in a Zen-like relaxed state: cooking is my favorite pastime. (We never eat take out.) I am a fanatical house-frau: clean and tidy, highly organized and efficient—not at all what you’d imagine from a creative person. I see a lot of friends for coffee and lunches. I love my friends. And because of my age (71 in 2017), there are plenty of appointments with medical people, dentists, physiotherapists, and hairdressers. The days are full, full, full. No time to write a thing…

So when you do write, how do you know you are done for the day?

When I can’t stand the difficulty any more.

The View Ahead

A book for Prince George, from Australia 2013

Are you writing anything at present?

I am always in the middle of writing one presentation or another. Half of my life seems to be spent in giving presentations: packing, traveling, presenting, recovering, traveling again, and so on. I also have three picture books in the pipeline, all of which need a lot of work—which isn’t being done.

Will readers be seeing anything from you in the near future, then?

Two new books are due out in 2019: one in Australia and one in America, both illustrated by award-winning, famous illustrators. I’m very excited.

With all of your busyness, do you ever plan to put away your pen and retire?

I can’t retire, unfortunately. Work comes into the house every day, and that would always be the case, even if I stopped writing tomorrow. But I’ll stop writing only when the ideas stop coming.

Will you be donating your papers and works to an educational institution?

My papers have already been donated to the National Archives in Canberra, Australia.

When all is said and done, what do you hope your legacy will be?

I hope I am remembered as an adored writer for many generations of children and families. I also want to be remembered for being an advocate for literacy, multiculturalism and human rights.

Fox with refugees in Adelaide, 2017

Bio

Fox with family, 1953

Mem Fox was born in Australia, grew up in Africa, went to drama school in England, and came back to Australia in 1970, at the age of 22.

In 1983, Fox became Australia’s bestselling writer. Possum Magic, her first book, is still available in hardback after 34 years and has become a beacon of children’s literature for millions of Australian families. She has written over 40 children’s books and several nonfiction books for adults. Her books have been translated into 21 languages, and many of them have been international bestsellers.

Fox is a retired Associate Professor of Literacy Studies from Flinders University, South Australia, where she taught teachers for 24 years. She has received many civic honors and awards and three honorary doctorates. Her latest book, I’m Australian Too, takes her back to where she started: her passion for Australia. She hopes it will spark spirited discussions about Australian-ness, create an awareness of Australian immigration over the centuries, and begin to calm the rising racism in Australia.

Fox is a retired Associate Professor of Literacy Studies from Flinders University, South Australia, where she taught teachers for 24 years. She has received many civic honors and awards and three honorary doctorates. Her latest book, I’m Australian Too, takes her back to where she started: her passion for Australia. She hopes it will spark spirited discussions about Australian-ness, create an awareness of Australian immigration over the centuries, and begin to calm the rising racism in Australia.

Fox lives in Adelaide, Australia. Visit her at memfox.com.

Fox’s Adores and Abhors

- My favorite colors are pink and green.

- I am a fruit fanatic: persimmons and figs are my favorites.

- I have traveled the world since childhood. My favorite place is now my own bed in my own house.

- I collect green paper clips.

- I abhor racism of any kind.

- I abhor junk food.

- I abhor sewing.

- I abhor huge houses and huge cars.

- I abhor politicians who are eager to follow, but reluctant to lead.

Excerpt from I’m Australian Too (Scholastic Australia, 2017)

We open doors to strangers,

Yes, everyone’s a friend.

Australia Fair is ours to share,

where broken hearts can mend.

What journeys we have travelled,

from countries near and far!

Together now, we live in peace

beneath the Southern Star.

Ten Read-aloud Commandments

- Spend at least ten wildly happy minutes every single day reading aloud. From birth!

- Read at least three stories a day: it may be the same story three times. Children need to hear a thousand stories before they can begin to learn to read. Or the same story a thousand times!

- Read aloud with animation. Listen to your own voice and don’t be dull, or flat, or boring. Hang loose and be loud, have fun and laugh a lot.

- Read with joy and enjoyment: real enjoyment for yourself and great joy for the listeners.

- Read the stories that your child loves, over and over, and over again, and always read in the same ‘tune’ for each book: i.e. with the same intonations and volume and speed, on each page, each time.

- Let children hear lots of language by talking to them constantly about the pictures, or anything else connected to the book; or sing any old song that you can remember; or say nursery rhymes in a bouncy way; or be noisy together doing clapping games.

- Look for rhyme, rhythm or repetition in books for young children, and make sure the books are really short.

- Play games with the things that you and the child can see on the page, such as letting kids finish rhymes, and finding the letters that start the child’s name and yours, remembering that it’s never work, it’s always a fabulous game.

- Never ever teach reading, or get tense around books.

- Please read aloud every day because you just adore being with your child, not because it’s the right thing to do.