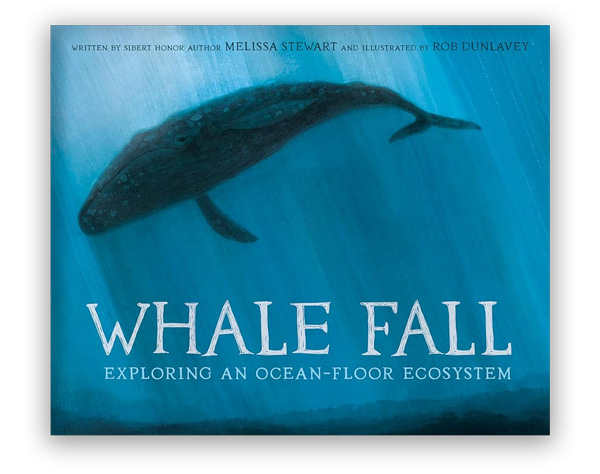

Melissa Stewart’s website notes that if she were to be a type of punctuation, she’d be a question mark. That’s the perfect choice for a writer who enjoys asking questions, researching new topics, and writing children’s nonfiction, including more than 200 science books for young readers. Most recently, her book Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem (Random House Studio, 2023) was honored as the picture book winner of the 2024 AAAS/Subaru SB&F Prize for Excellence in Science Books and as a 2024 ALSC Notable Children’s Book. Stewart carries her advocacy into the world of educators as well, maintaining the award-winning blog Celebrating Nonfiction and creating educator’s guides that offer an impressive range of ideas for using nonfiction books to inspire students to be more enthusiastic readers and writers.

Here, Stewart talks with Lisa Bullard about how she researches and writes her books, the childhood moment that inspired her impressive career, and the ways children can generate, research, and write about their own ideas.

Could you lead young readers through the start-to-finish steps of creating one of your books?

Every book is different. Sometimes books take five, ten, fifteen years (or even more) to write. And that doesn’t include everything that happens after a publisher agrees to publish it: editing, designing, illustrating, printing. But Whale Fall was an exception; the whole process was blissfully quick.

In 2019, I stumbled upon an article about zombie worms, aka bone-eating snot flower worms, while writing a book called Ick! Delightfully Disgusting Animal Dinners, Dwellings, and Defenses (National Geographic Kids, 2020). I included some information about them in the “Dwellings” section of that book, but I knew I wanted to write more about these unusual marine worms one day.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, all my school visits were canceled and I had plenty of time for research. As I began reading more about zombie worms, my mind was blown. I was completely captivated by the incredible collection of critters that live in, on, and around a whale fall. I knew I had to write a book about them.

The reason it often takes me many years to write a book is because I’m searching for just the right text structure. But in this case, I knew immediately that a chronological sequence structure would be the perfect choice. This allowed me to write the book in just a few months.

My critique group loved the manuscript and encouraged me to send it out right away. Often, it can take many months to hear back from editors, but this time I got the go-ahead the very next day! I was thrilled.

And when the editor sent me samples of Rob Dunlavey’s stunning artwork, I was even more excited. I knew he was the perfect artist to illustrate the book.

Creating the fabulous art and designing the book took about two years, and then it took another six months or so for the book to be printed. Whale Fall was released into the world in March 2023—four years from start to finish.

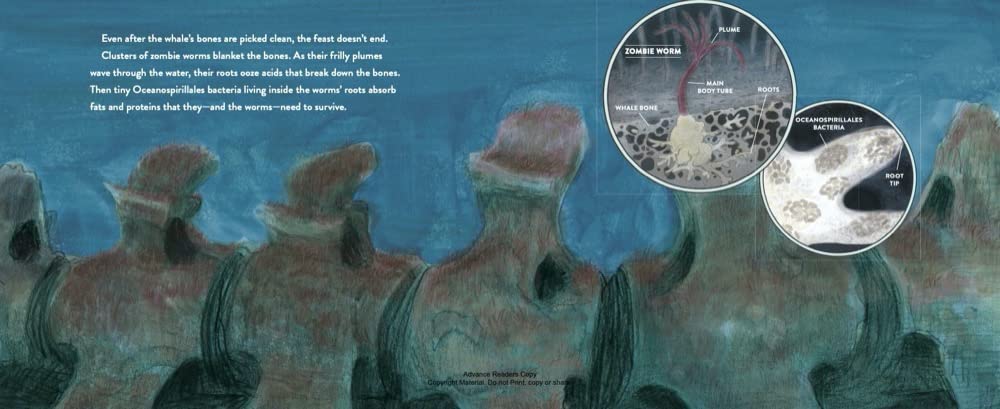

Spread from Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem

What’s the longest time it’s taken from the point where you first started writing a book to where you held that book in your hands?

I have a book scheduled for 2026 that I started writing in 2007, so that will be nineteen years.

One of the things that stands out about your writing is your unexpected take on “common” subjects. For example, there are plenty of books about hibernation, but your title Summertime Sleepers: Animals that Estivate (Charlesbridge, 2021) focuses on creatures that extend their sleep when it’s hot or dry. How do you come up with your intriguing ideas?

I choose topics that I find fascinating, and I hope kids will share my excitement. Who knew some animals snooze through summer or that whale falls can support a thriving community of creatures for as long as fifty years? I discovered these incredible natural phenomena, and I just HAD to share them with other people.

For me, ideas are everywhere. They come from books and articles I read, conversations with other people, places I visit, and experiences I have. The hard part isn’t getting ideas, it’s keeping track of them.

That’s why I have an Idea Board in my office. Anytime I have an idea or a question, or anytime I hear a tantalizing tidbit, I write it on a scrap of paper and tack it up there. Then when it’s time to start a new book, I look at all those ideas and choose one. When the pandemic hit, the idea of writing about whale falls was right there waiting for me.

Ideas are everywhere.”

What advice do you have for students who are challenged by coming up with their own writing ideas?

Young writers can mimic my Ideal Board technique by creating what I call an Idea Incubator—a bulleted list of potential topics on the last page of their writer’s notebook. Every time they have an idea or question about something they see, read, or experience, they can add it to their Idea Incubator. They can also include cool facts they come across. If students start keeping this list at the beginning of the year, when it’s time to do some nonfiction writing, they have plenty of ideas to choose from. They can also share their list with a partner and the two students can brainstorm even more ideas together.

Melissa Stewart’s Books for Educators

5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books

5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books

By Melissa Stewart and Marlene Correia

This guide presents a simple, practical system for sorting nonfiction into five major categories (active, browseable, traditional, expository literature, and narrative) and describes how classifying books in this way can help teachers and students effectively utilize the books in a school setting.

Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep: 50 Award-Winning Children’s Book Authors Share the Secret of Engaging Writing

Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep: 50 Award-Winning Children’s Book Authors Share the Secret of Engaging Writing

Edited by Melissa Stewart

Some of today’s most celebrated writers for children share essays that describe a critical part of the informational writing process that is often left out of classroom instruction. In addition, the guide includes a wide range of tips, tools, teaching strategies, and activity ideas to help students craft rich, unique prose.

Perfect Pairs: Using Fiction & Nonfiction Picture Books to Teach Life Science, K-2

Perfect Pairs: Using Fiction & Nonfiction Picture Books to Teach Life Science, K-2

By Melissa Stewart and Nancy Chesley

Each of the twenty-two lessons in this guide is built around a pair of award-winning trade picture books. After extracting critical content from the books, students in grades K-2 participate in an inquiry-based investigative process to explore key life science concepts.

Perfect Pairs: Using Fiction & Nonfiction Picture Books to Teach Life Science, Grades 3-5

Perfect Pairs: Using Fiction & Nonfiction Picture Books to Teach Life Science, Grades 3-5

By Melissa Stewart and Nancy Chesley

Each of the twenty lessons in this guide is built around a pair of award-winning trade picture books. After extracting critical content from the books, students in grades 3-5 participate in an inquiry-based investigative process to explore key life science concepts.

The way you weave your words together invites readers to consider your topic in a fresh way. Whale Fall, for example, is about decomposition, but your language is artful and majestic. Once you have an idea, how do you decide what voice to adopt when conveying it?

While writing Whale Fall, I had the word “reverence” written on a sticky note attached to my computer screen. That’s the feeling I wanted the book to have.

I love whales, and I know a lot of kids do too. The death of such a magnificent creature is sad and could be quite upsetting to some young readers. I wanted to respect and honor those feelings, and I wanted to respect and honor the whales themselves. They provide a bountiful gift to their ocean environment. Their death fosters and fuels new life—thousands of species, millions of individual creatures. Isn’t that astonishing?

I strove to craft a lyrical, reverent, respectful voice by paying close attention to word choice, figurative language, and text scaffolding. But that’s only half the story. Rob Dunlavey’s art plays a critical role in conveying the feeling I was trying to achieve.

How do you dig deeper to find the lesser-known details that make Whale Fall and your other titles stand out?

Because there’s so little information about whale falls available in print, it was critical to have the help of scientists studying them. These researchers usually spend their springs and summers aboard research vessels in the ocean and are hard to reach. But the COVID lockdown meant that scientists were stuck at home. They were more than happy to spend time helping me understand how all the creatures living on a whale fall interact with one another.

Scientists also vetted the art. Their guidance made it possible for Rob Dunlavey to create microscopic images unlike anything ever published before—not even in an adult book or a scientific paper. It’s exciting to do something so cutting-edge in a children’s book!

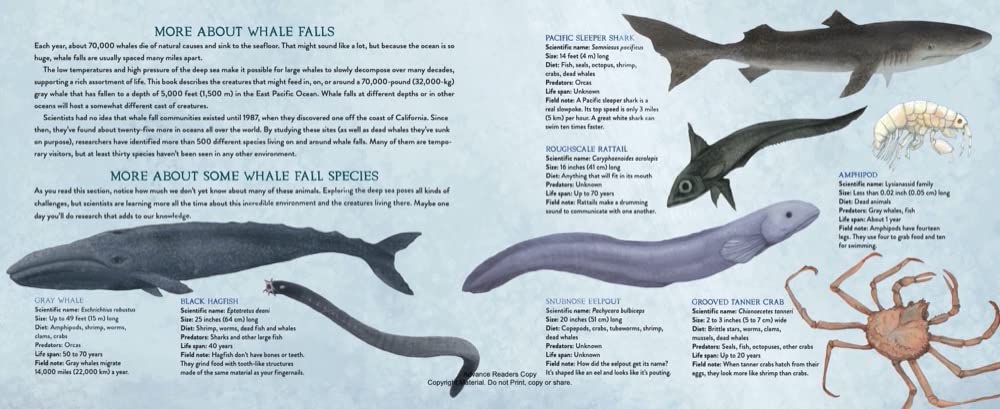

Spreads from Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem

What suggestions do you have for students who are learning how to do research?

Research is like a treasure hunt—a quest for tantalizing tidbits that make your writing unique and fascinating.

I encourage kids to do firsthand research. If they are writing about an animal, choose one they can observe in their backyard or the school playground or at a local park. Observe live animals at zoos or on webcams. Watch YouTube videos with an older sibling or adult.

Depending on their topic, young researchers can interview people in their community—firefighters, town workers, a neighbor, their grandparents, a librarian. Everyone is an expert on something.

What makes research fun for professional writers is the creativity of it, the out-of-the-box thinking. Students should have opportunities to do this kind of research, so they understand why it’s a joyful, intellectually stimulating process.

Turn Your Students Into Stronger Writers With These Great Resources From Melissa Stewart

Research is like a treasure hunt—a quest for tantalizing tidbits that make your writing unique and fascinating.”

What’s your advice for young people who want to become writers?

You already are! Anyone who puts pen to paper because they have something they want to share is a writer.

Becoming a published writer takes patience and practice, so keep on trying. Look for inspiration everywhere. Experiment with a few different ways of expressing the ideas you want to share and then choose the clearest, most interesting version.

Anyone who puts pen to paper because they have something they want to share is a writer.”

What would you like to share with young readers about your growing-up years and how they contributed to who you are today?

I was very fortunate to grow up in rural Massachusetts. My parents owned ten acres of land on one side of the street, and there was a national forest on the other side of the street. So, my childhood was spent immersed in the natural world and that had a big influence on the person—and the writer—I’ve become.

One day, when I was about eight years old, my father took my brother and me on a hike to an unfamiliar area of woods. He asked if we noticed anything unusual.

My brother and I looked around. We looked at each other. We shook our heads.

But then, suddenly, the answer came to me. “All the trees seem kind of small,” I said.

My dad nodded. He explained that there had been a fire in the area about twenty-five years earlier. All the trees had burned, and many animals had died, but over time, the forest had recovered.

It was an aha moment for me because I instantly understood the power of nature to regenerate itself. I also realized that a field, a forest—any natural place—has stories to tell, and I could discover those stories just by looking.

Now many years later, I’ve written more than 200 children’s books about science and nature. And I know that my personal mission, the purpose of my writing, is to share the beauty and wonder of the natural world with children of all ages. If one of my books inspires a child to lift a rock and look underneath, or chase after a butterfly just to see where it’s going, then my job is done.

If one of my books inspires a child to lift a rock and look underneath, or chase after a butterfly just to see where it’s going, then my job is done.”

What other natural places would you like to visit?

I’ve spent most of my life in and around the deciduous forests of the Northeast, so I love traveling to other ecosystems. I’ve visited the plains of North Dakota and the savannas of Africa, the tropical rain forests of Costa Rica and the temperate rain forests of Vancouver Island, and the deserts of the Galapagos Islands and Arizona. But I’ve never been to the tundra. I hope that one day I can visit Denali National Park in Alaska.

What’s the best compliment you hear from young readers?

When I read a book to a group of children and just as I finish, one of them whispers, “Read it again.”

What would you like to tell your fans about your newest book?

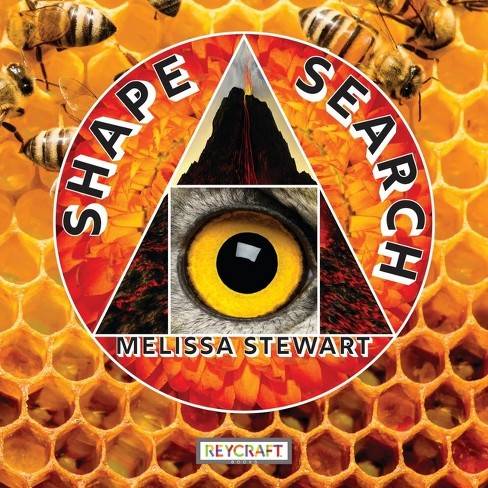

In February 2024, I welcomed a rhyming, photo-illustrated picture book called Shape Search into the world. It’s an invitation to notice and hunt for a wide variety of shapes in nature.

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

Website: melissa-stewart.com/

Facebook: facebook.com/melissa.stewart.33865

Twitter: twitter.com/mstewartscience

Bluesky: mstewartscience.bsky.social

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/meslissastewartscience/