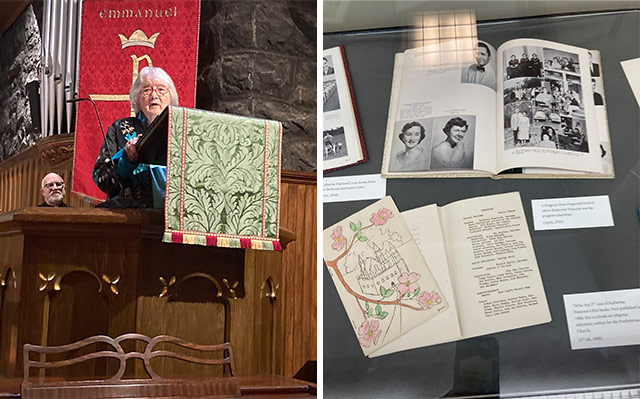

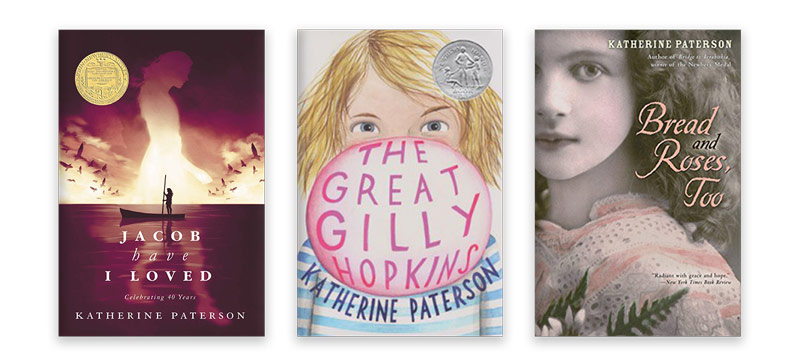

Katherine Paterson has been named a Living Legend by the Library of Congress in acknowledgment of her two Newbery Medals, her two National Book Awards, and the profound impact her books have had on readers. It’s difficult to summarize such a long and celebrated career; as Paterson herself says, when thinking over the decades of responses she’s received from her young fans, “Over fifty years and forty-six books, there are many stories.” Each one of those stories reveals an individual reader who holds one or more of Paterson’s books close to their heart.

Paterson’s latest book is the true story of someone Paterson believes is a literacy hero. Jella Lepman and Her Library of Dreams (Chronicle, 2025, featuring artwork by Sally Deng) is the illustrated biography of a Jewish German woman who fled Nazi Germany in 1936, but returned after World War II to advise the American Army on the needs of Germany’s women and children. Lepman focused on finding a way to give the children of Germany access to the world’s best children’s books, refusing to give up on her dream despite encountering repeated obstacles. This riveting account reveals how Lepman persevered and demonstrated that books are the ideal way to build bridges between the children of the world. Her determination to lay a foundation of peace for young people whose childhoods had been lost to war led to the eventual establishment of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY).

Here, Paterson talks with Lisa Bullard about how she became fascinated by Jella Lepman’s story; shares a favorite anecdote about one of her fans; and reveals which of her books has most surprised her.

What else would you like to say about Jella Lepman and Her Library of Dreams? Why was it important to you to share Jella’s story?

I first heard about Jella Lepman when I was invited to take part in a group who called themselves “U.S. Friends of IBBY.” I became fascinated with this woman who had not only established the largest library in the world devoted to books for children and young people, but had also been instrumental in establishing the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Why didn’t more people know about her—a true hero for literacy and for peace? She had written a sort of memoir, but more was needed. I knew someone should write a book that would appeal to people who had never heard of her or of IBBY.

Why didn’t more people know about [Jella Lepman]—a true hero for literacy and for peace?”

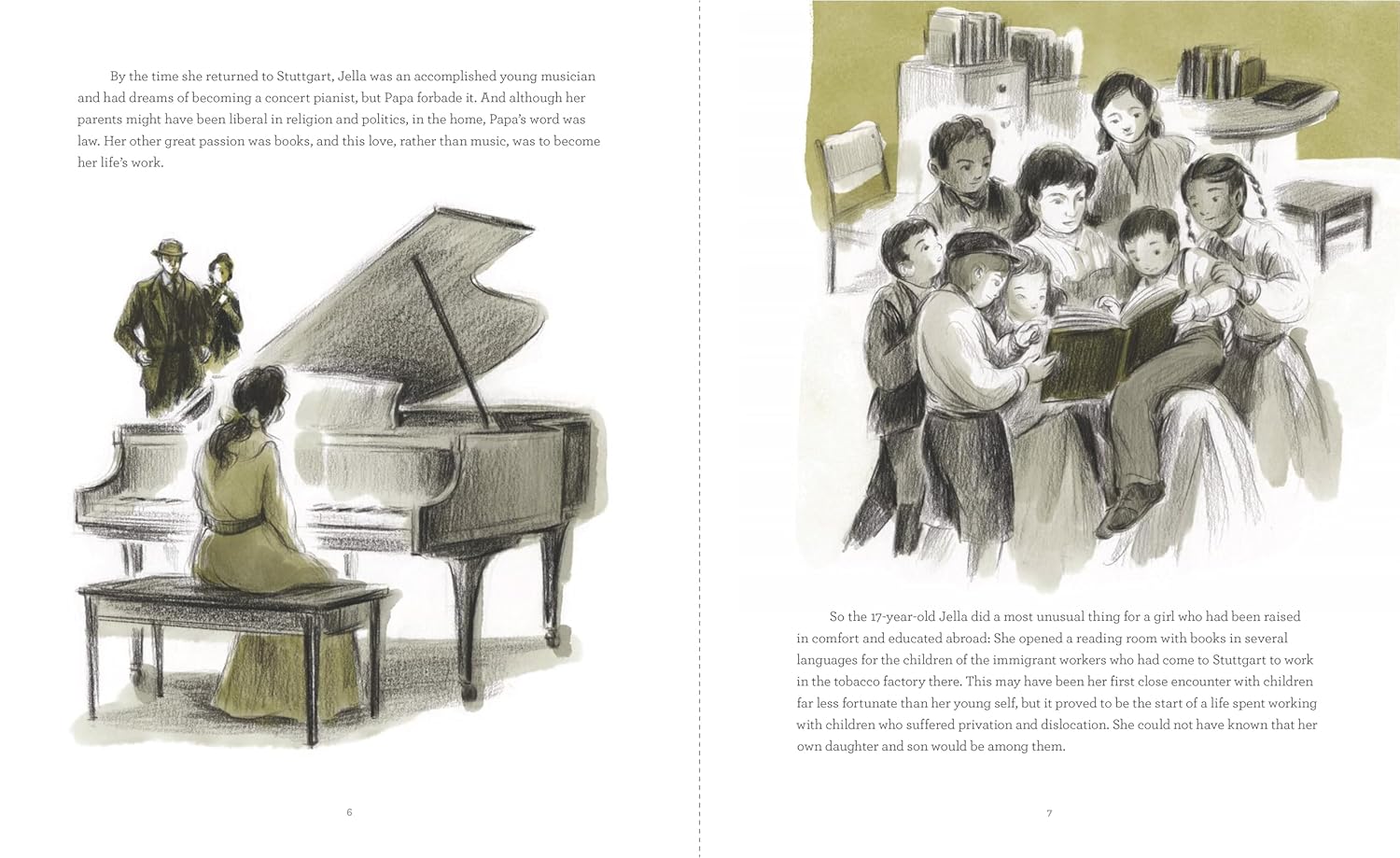

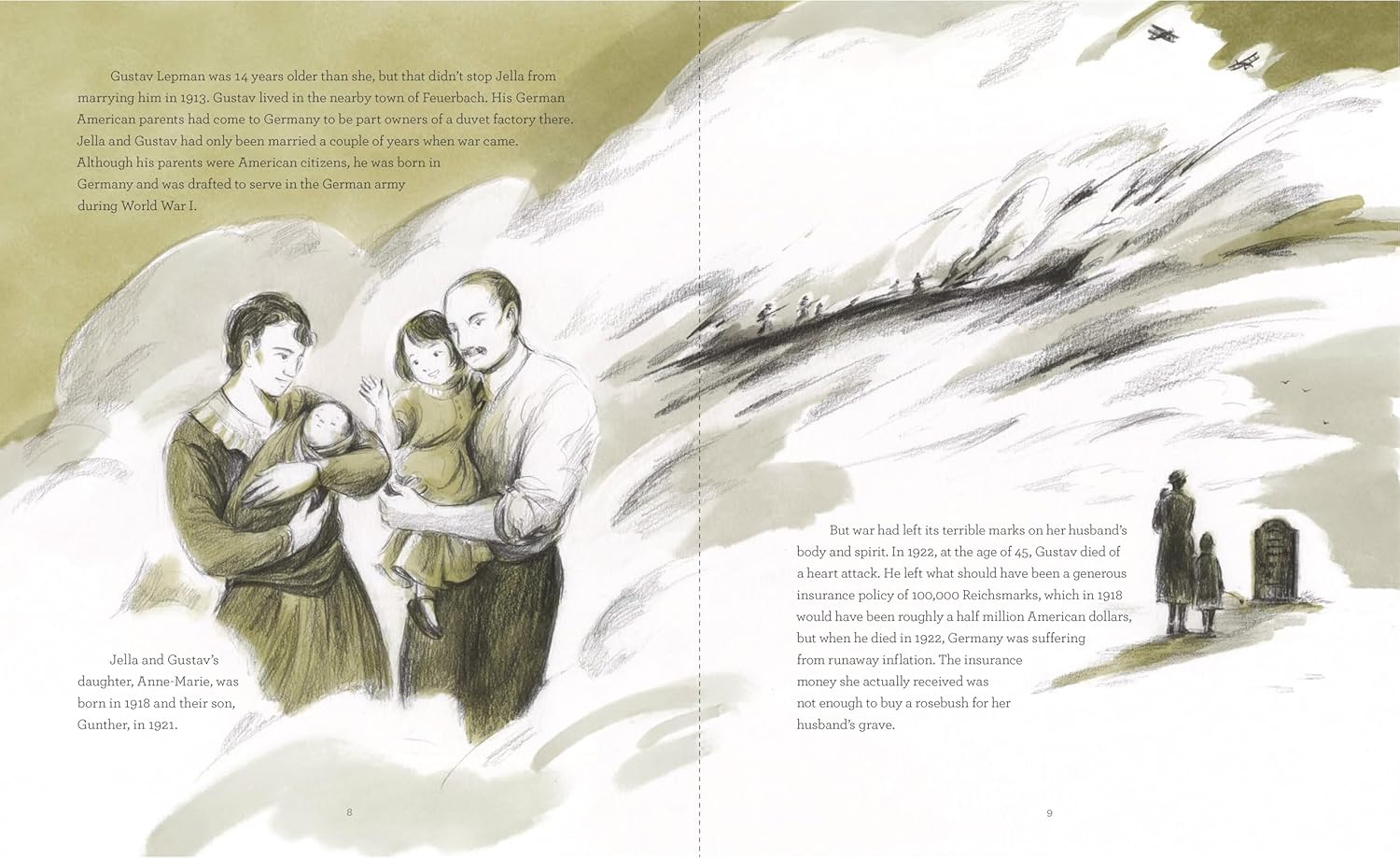

Spreads from Jella Lepman and Her Library of Dreams

Three words that came to me as I read Lepman’s story were resilient, possibility, and resourceful. Are there other words you’d like to add as important takeaways for your readers?

How about determined, daring, and unstoppable?

What’s your best advice for young people who, like Jella Lepman, have a dream that they want to pursue?

Dream on. As you mature, the dream might change, but use it to develop your imagination for life. I think it was Einstein who said that imagination is more important than knowledge.

An Excerpt From Katherine Paterson’s Newest Book, Jella Lepman and Her Library of Dreams

“It was obvious that the children of Germany whom Jella had come home to help were in desperate need of food, of clothing, of safe shelter. Elly Heuss-Knapp, whose husband later became president of West Germany, told Jella that while soup kitchens and care packages were all good and necessary, ‘nourishment for the soul’ was even more important.

“For Jella that nourishment had always come from books. She began to talk to publishers and booksellers. One bookseller told her that the people were hungry for the books from the free world that had been banned for 12 years.

“‘And children’s books?’ Jella asked.

“‘Children’s books? Oh, there aren’t any of those left whatsoever. Those are more needed than all the others.’”

Copyright © 2025 by Katherine Paterson, excerpted from Jella Lepman and Her Library of Dreams, used by permission of the publisher, Chronicle Books.

Many readers are huge fans of your fiction, and this is a nonfiction biography— but you certainly use those same storytelling skills to sweep readers up in Jella Lepman’s true story. Could you share a couple of your favorite storytelling tips with student writers?

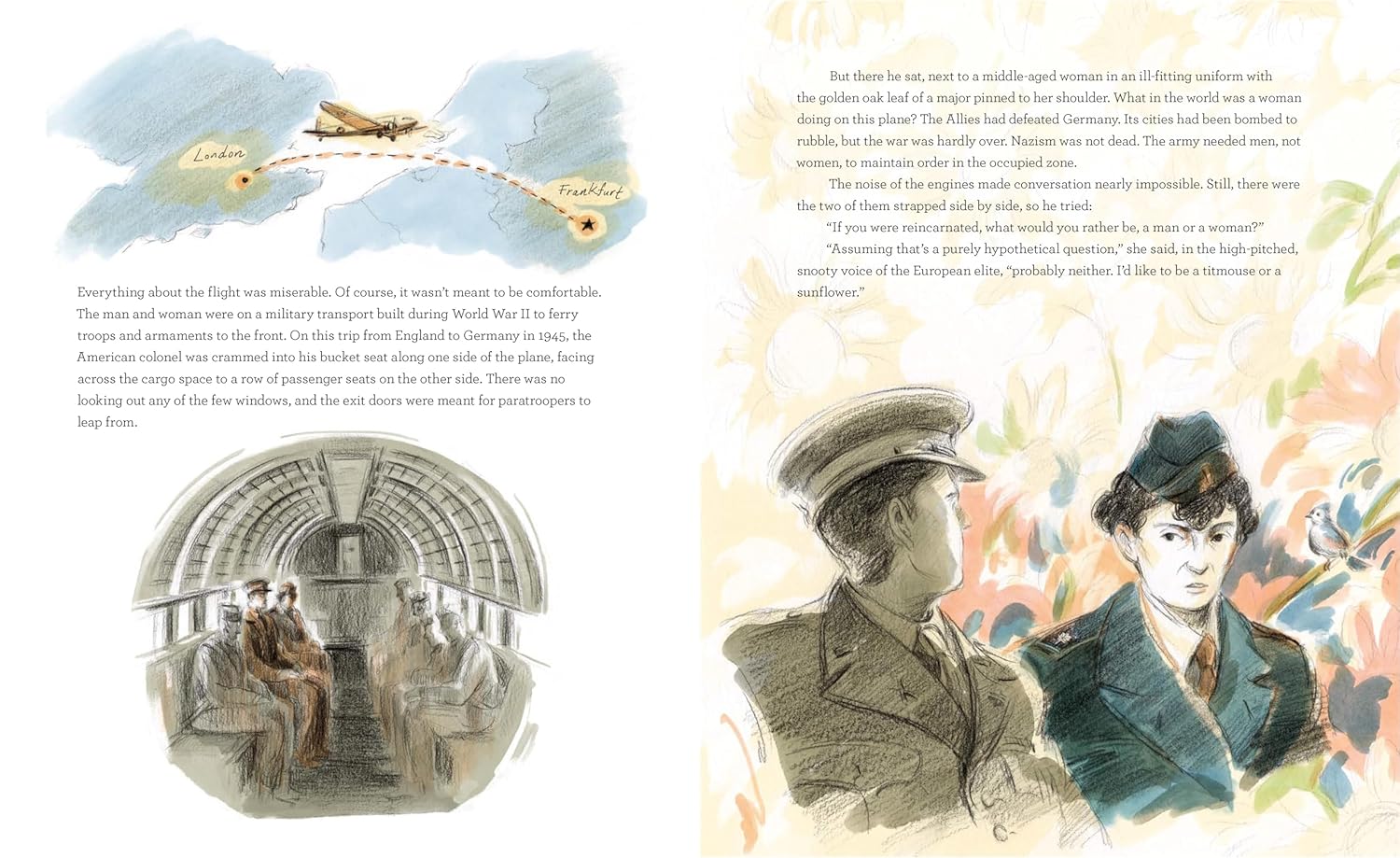

One: Love your characters, even the villains. Two: Listen to the story. I believe that the story lets me know how it wants to be told. In this case, the story of the airplane trip with the pompous colonel was irresistible as a starting place.

I believe that the story lets me know how it wants to be told.”

Do you have a typical starting point when you set out to draft a new book?

Each book has its own starting point: sometimes it’s a character, as in this case, sometimes a plot, sometimes a setting or an idea.

What’s your favorite part of creating books for young readers?

Having readers is absolutely the best part of being a writer. And writers for the young are the most blessed writers of all. Young readers will go deep. If they love your book, they’ll read it many times, play out scenes with friends, and even save it to pass on to their own children. How many writers for the old can match that?

Having readers is absolutely the best part of being a writer. And writers for the young are the most blessed writers of all.”

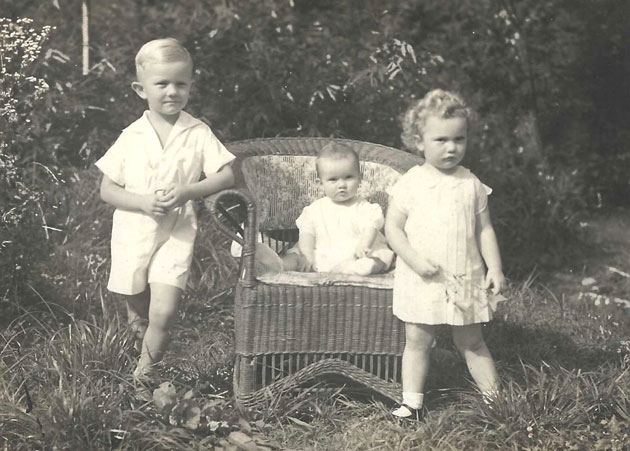

How has your childhood contributed to your writing career?

I was born in China and was bilingual until we left China and came to the States. I think that early thinking and speaking in two languages is good for our minds. Of course, when I came to America, I was a total outsider. When people think you are weird, and you have no friends, you become very observant of people’s behavior because you’re trying to figure out how to fit in. It’s a helpful skill for a writer to develop.

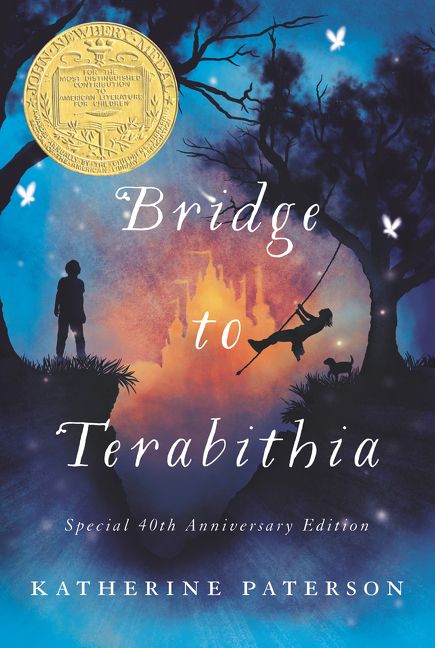

Which of your books has most surprised you?

Well, Bridge to Terabithia (HarperCollins, 1977) continues to sell better than all my other books put together. I wrote it to try to make sense of a tragedy that made no sense, and it did help somehow. But each of my novels has grown out of my trying to make sense of something in my life. I don’t write to provide answers, I write to find answers.

I don’t write to provide answers, I write to find answers.”

What’s your favorite anecdote about the power that your books have had in the lives of your young readers?

Over fifty years and forty-six books, there are many stories. One I love is the story of Eddy, who hated school and books until his special ed teacher read The Great Gilly Hopkins (HarperCollins, 1978) aloud to her class. Even though he had never learned to read, he took the book out of the library and carried it around with him. He was determined to read it for himself, and eventually he could and did. When the librarian told me about Eddy, I sent him a copy of the book so he could return the library copy and keep reading.

Can you share any details about your forthcoming books?

Well, right now I’m trying to get together the essays I’ve written over the years and fashion them into a book about reading and writing children’s books that would be worth reading.

What are the best ways for educators and librarians to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

My son helps me with my website—katherinepaterson.com—and my Facebook page, which is more up to date. I’m too old for too much of the jazzy stuff authors are supposed to do. I was raised not to “toot my own horn,” so I find self-promotion embarrassing.