When we read, we connect with others without the fear of rejection. Every page is promised to us; it is in our hand, waiting. When we ‘read’ without words, we are left to infer, and to infer means more risk…we might be wrong, after all. Yet, it doesn’t always play out that way because without the absolute definable arrangement of words, there’s no one there to say what is wrong or what is right. Your interpretations are adequate. Reading becomes inspection and your inspections become meaningful because your exploration is dependent upon willing participation. You have to look again and again. There are many ways to see something, but do we truly perceive what we see?

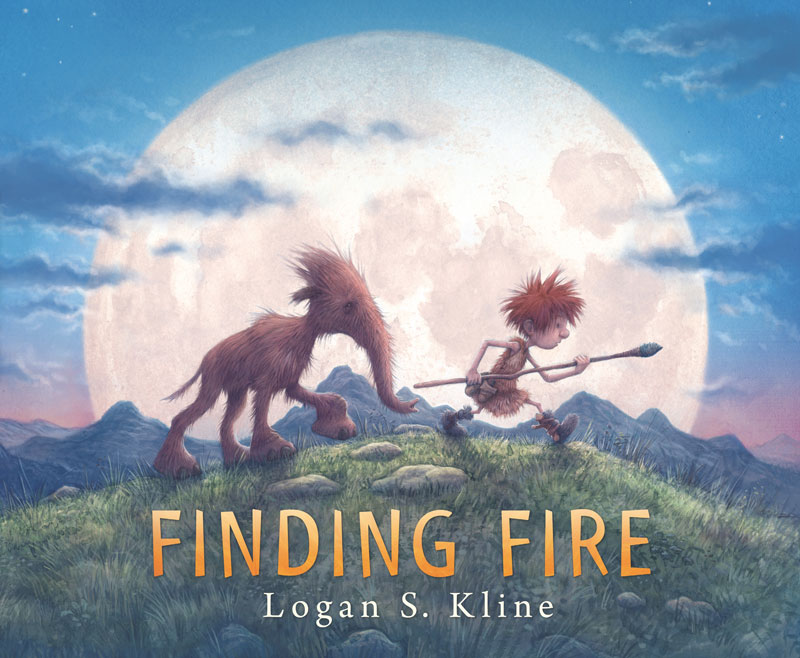

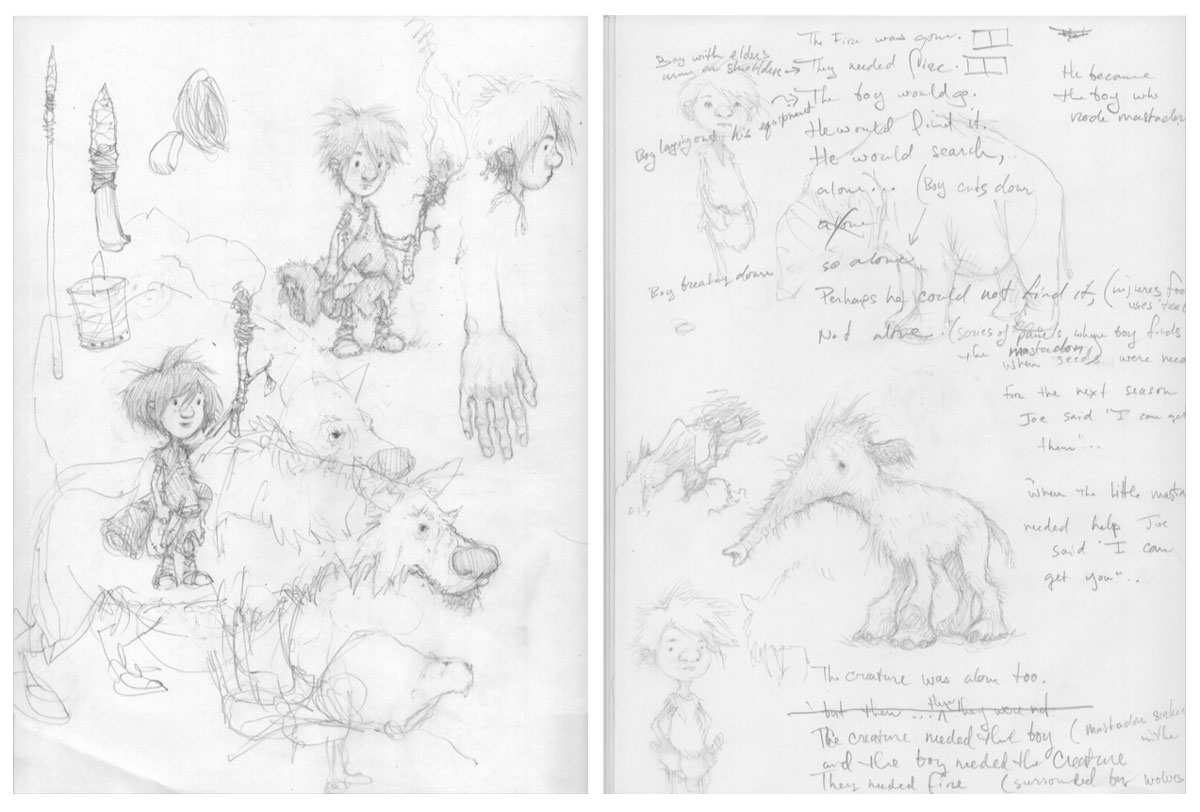

Now, that’s a lot of fancy talk, especially when you consider that Finding Fire started with words…lots of words. I know that seems like a confession, particularly after an opening paragraph like that. You see, when I started Finding Fire, I wanted it to be accessible, a little challenging perhaps (I was hopeful that it would be received well enough that people would want to put some effort into it), but still accessible, and I thought, for a picture book, that meant words. I wanted simple, unfussy words that flowed when spoken, and satisfied the ear when heard.

That was the plan anyway…but after the offers were made, a publisher chosen, and a contract had been signed, my editor asked, “What do you think about the idea of going wordless?” Huh? What? My book? This book? Well, hold on a minute…I worked hard on those words. I don’t think it will make sense without the words, right? You need those…right?

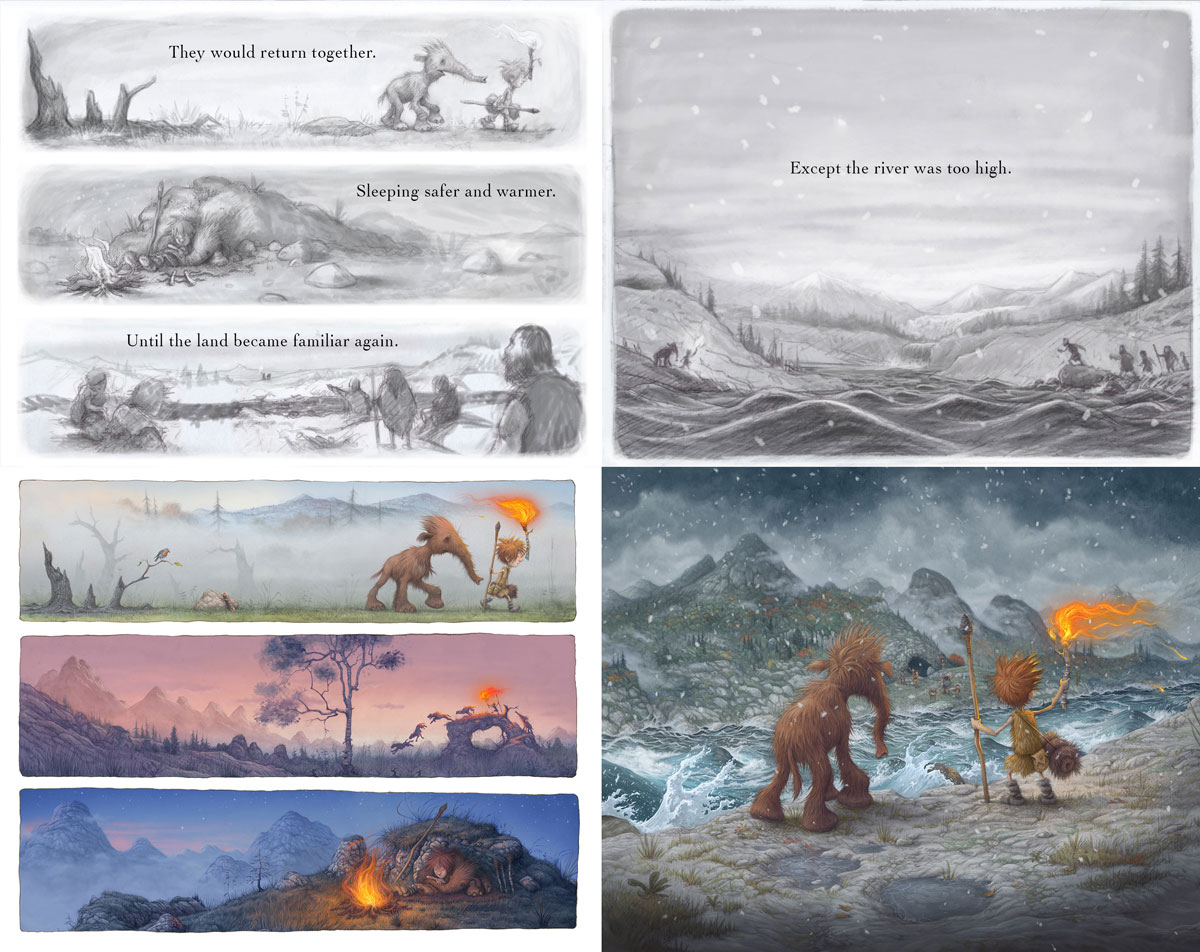

Don’t get me wrong; I love wordless books. I always assumed I would make one. I have in-progress dummy books on my shelf and they have all been wordless from their initial conception. But Finding Fire started with a few character sketches and then the words just tumbled out of my head. It was strange and thrilling. The words came so fast, I was almost frantic trying to get them down. I was worried I’d lose them. I knew that I would need to tweak some bits; maybe some editing here and there, maybe a rewrite (or two). But still, it was all there — an entire story. I’d never really had this experience with words before. I had it plenty of times with images; that is a constant for me. I’m an illustrator before anything else. Yet, writing has always been an aspirational endeavor for me; full of promise, but rarely success. The text for Finding Fire was an existential realization; I was now a writer as well as an illustrator and that felt good to say.

However, here is something I realized along the way: Words and art do not need each other. There are many great books out there that do not need illustrations. There are many great works of visual art that would not beenhanced if we wrote a few choice words on them. That said, we obviously enjoy putting words and images together; we do it all the time and for a variety of reasons. The paradox of picture books is that they create a situation where two things that do not need each other, find themselves in a desperate need of one another. All for the sake of a task that can range from poignantly simple to gobsmackingly complicated. The real challenge to the craftsmanship of the artist and writer is creating a situation that does not feel forced. For me, this comes as the result of a great deal of revision and discussion.

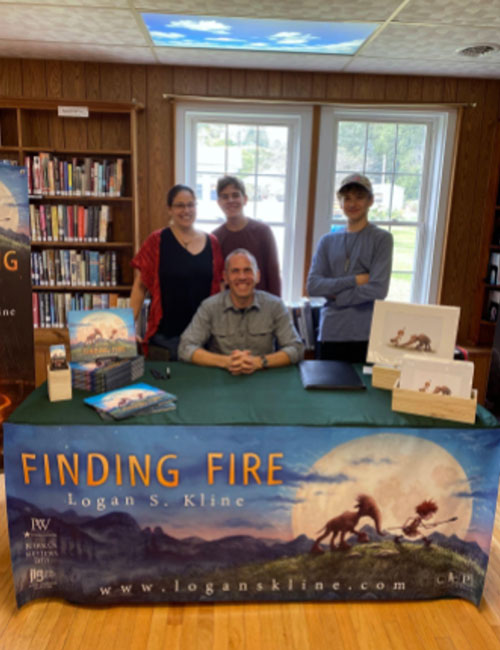

My family is my go-to for the beginning of every creative discussion. By the time I had to make a decision, I had a lot of voices tumbling around in my head.

From my son, “Dad, are you going to let them take away the words?”

To my brother, “It’s strange that the publishers want to go wordless. When I buy a book for my kids, it’s because I want to teach them how to read.”

To my agent, “It just goes to show how well the illustrations tell the story. Maybe it’s for the best…”

To an elementary school teacher, “No, keep the words out. This is great for kids; they have such a hard time with inference.”

Oh boy…what a dilemma. I love to ruminate, to ponder, to dwell on this or that, but this was a doozy. After alot of consideration, it all boiled down to one simple sentiment: Is the book better without the text? So, I stripped the words from the dummy book, reprinted the pages, and stitched it all together again. I still remember handing it over to my wife (my first editor). I chewed at my fingernails waiting for her to flip through the book and give her final verdict. Keep in mind, she was adamant about not letting them take out the words.

“I hate to say it hun, but it’s better. I look at your illustrations more without the words; they tell the story without the text.” What was going on? My goodness, all that time…over two years of working that dummy book. It was like finding out you run faster without your left leg. With words, the reading experience had been shallow. The illustrations, which I had filled with specific information for revealing character and plot, were seen as superfluous. As one of my siblings pointed out, with the words included, he would read one line and immediately jump to the next line of text ignoring (or missing) any imagery that may have given critical information. Without the words, he examined the story more carefully. He gleaned a deeper understanding of the plot, caught on to the mood of each spread, delighted in details of the illustrations, and picked up on the emotional state of the characters.

My editor was right—it was better without the text. My final decision was what we published—a nearly wordless picture book. The first 30 words we kept, and the rest we left to live silently in older, unpublished versions of the story. I still had yet to create the final illustrations, but there it was. In this process, the words turned out to be the temporary scaffolding that gave the illustrations support until they could carry the weight of the story.

But all of this is orbital to the heart of why I or anyone else tell a story. Regardless of how we tell it, or what form the final story takes, at our core we tell stories out of a desire to connect. With Finding Fire, it is my hope that it connects with a child’s internal desire for adventure, courage, companionship, and the satisfaction of being brave for those you love and care about.