A recent New York Times article identified children as the “pandemic’s ‘forgotten grievers.’” So, author/illustrator Matthew Cordell’s poignant 2021 picture book, Bear Island (Feiwel and Friends), is especially timely, providing a wonderful opportunity for educators and others to help young readers process the complicated feelings surrounding loss. In the story, Louise struggles with the strong emotions she experiences when her family’s beloved pet dog dies—slowly working her way toward healing by immersing herself in the natural world and sharing her pain. As educator Katie Cunningham says in “The Classroom Bookshelf” blog, “Bear Island opens the door for children to talk about loss and sadness through a soulful narrative that offers a model for emotional recovery.”

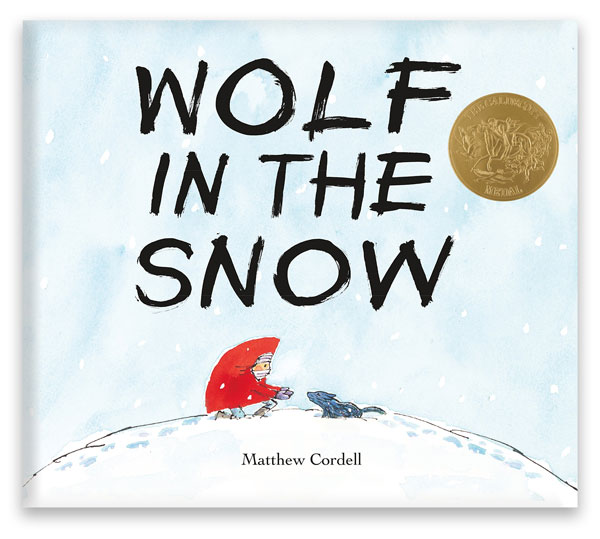

Cordell is also the winner of the 2018 Caldecott Medal for his picture book Wolf in the Snow, and his titles have appeared on many Best Books of the Year lists, including those by Horn Book Magazine and School Library Journal. Here, he talks with Lisa Bullard about guiding children through grief, his process of creating picture books, and how inspiring he finds it to write for his youngest readers.

The character in your recent picture book Bear Island is struggling with some of the most complex emotions that human beings can experience, and I was struck by how much confidence you have in young children’s ability to process complex stories. Have you always had that kind of faith in your readers?

My deep respect for and better understanding of children really developed in me after I became a dad. In the years between being a kid myself and having kids in my life, I was pretty intimidated by children and was always uneasy on the rare occasion we’d be in each other’s company. I never knew how to act, and I could sense how deeply insightful they were and that they could see how insecure I was, and it was horribly awkward. But then my wife and I had our daughter, Romy, and I was around children again in a big way, and so much changed. I saw up close how a child’s mind works, and I could see that, really, I could just be myself and they were certainly going to be themselves. It rocked my world so hard to see just how much I enjoyed being in the company of children. They are brimming with hope and curiosity and humor and potential. They are open to new things in ways that adults are not. And they are constantly being confronted with new ideas, concepts, and emotions—grief being one of those.

When my daughter was four years old, our cat, Tobin, died. We were all devastated, Romy included. It was the first time she’d experienced a loss. Her first reaction was she needed to be alone. And we could hear her crying alone for a bit in her bedroom with the door closed. Eventually she wanted to be with her mom and dad, but she needed to deal with it alone, too. And I’m the same way. I’ve thought about that moment often over the years; about how powerful a new experience like this is to a child, and about how complex they must be to handle something that big for the first time. I have so much respect for children and what they are capable of, and I’m inspired by them every day.

[Children] are brimming with hope and curiosity and humor and potential. They are open to new things in ways that adults are not.”

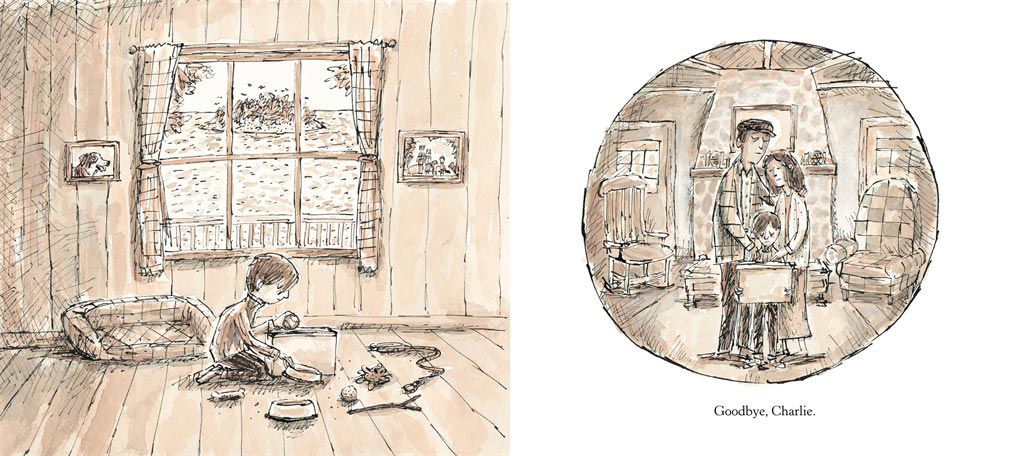

I love that you start the story in Bear Island through a series of illustrations that appear even before the title page. How did that approach come about?

Thank you, that’s a device I’ve used on several books over the years. In television or film, they call that sort of thing a “cold open,” when a bit of story opens up immediately, preceding a title screen or opening credits. Way back when, I’d seen one or two picture books use this method of dramatic opening, and I was happy to steal it for use in my own books!

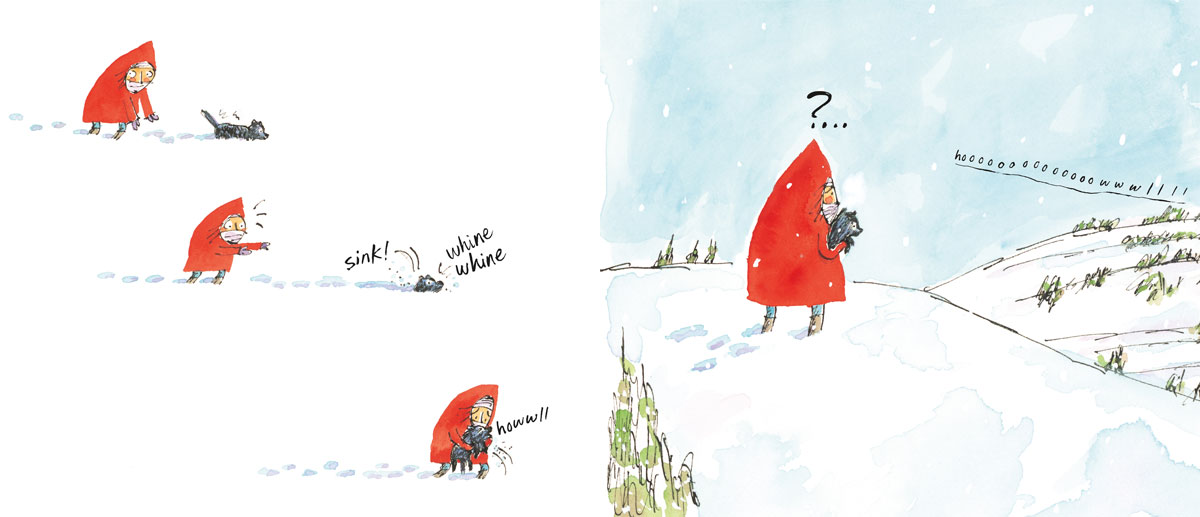

It’s notable how you use color to convey the shifting emotions in Bear Island, and it seems like a study of that could lead to an interesting classroom discussion. Do you have other suggestions about how educators can use picture books in the classroom?

Like color considerations, there are many things to pick apart in picture book mechanics and design. One of the things that fascinates me about picture books is how the words and the pictures work hand in hand to tell a story. It’s something most picture book readers probably take for granted, but it’s a finely honed craft to the people who make them. An interesting experiment to share with people (young and old) is to remove the words from a picture book and attempt to understand the story from the pictures alone. Or to remove the pictures and try to understand the story with the words alone. It won’t make sense. Then when you put them back together, that synergy is really obvious. This exercise doesn’t really apply to wordless picture books—which would be a whole other thing to study!

An interesting experiment to share with people (young and old) is to remove the words from a picture book and attempt to understand the story from the pictures alone.”

Speaking of wordless picture books, when I reread your 2018 Caldecott Medal winner, Wolf in the Snow (Feiwel and Friends, 2017), I actually forgot, for a moment, that I was having to “read” your illustrations because there isn’t really a written text. What’s your process for creating a wordless story?

Wow, that’s quite a compliment, really—the idea of being so pulled into a wordless book that one forgets to note the absence of words! The balance of words and pictures definitely varies from one book to the next. I’ve done several books that are either wordless or nearly wordless, so much of the story is told without the support of text. In almost all of these books, they started out with words—exposition and dialog—but for different reasons I pruned out the text from revision to revision. Wolf in the Snow started out that way. I didn’t originally intend for the book to be wordless, but due to the nature of the story—the scare and drama of a girl and wolf pup isolated in nature—I saw less and less need for any dialog or explanation. It made sense, in regards to the story, to extract all the words from the pages. Ironically, I feel it made the book louder to remove all the words.

Your books have been published in many different languages, including Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Spanish, French, and Italian. Does it influence how you approach your stories to know that readers from such different backgrounds will read the book?

That’s an interesting question! Honestly, I’m not sure how much thought I give it, trying to reach and satisfy the different mindsets of children from different corners of the world. A book idea, for me, usually starts with something that I love or find inspiring or funny or challenging and interesting. And it evolves into a thing that I want my audience to be able to interpret and make their own.

A book idea, for me, usually starts with something that I love or find inspiring or funny or challenging and interesting. And it evolves into a thing that I want my audience to be able to interpret and make their own.”

How would you compare the joys and challenges of creating a book as both the author and illustrator versus creating the illustrations for another writer’s words?

There are definite plusses to both scenarios. When I’m illustrator-only, the pressure’s off in terms of coming up with a central idea and manuscript. Which can be quite daunting when starting a new book of my own! And the promotion responsibilities are shared between author and illustrator, which is quite nice to work as a team. In terms of being both author and illustrator of a book, there’s a really gratifying feeling to being able to pull off both tasks. For years in the beginning of my career, I was illustrator-only on all my books, an illustrator who also wanted to write but wasn’t very good at it. Once I eventually improved my writing and was able to both write and illustrate, it was especially thrilling. So that element of excitement still exists for me whenever I have an idea for a book that I’m able to tackle individually.

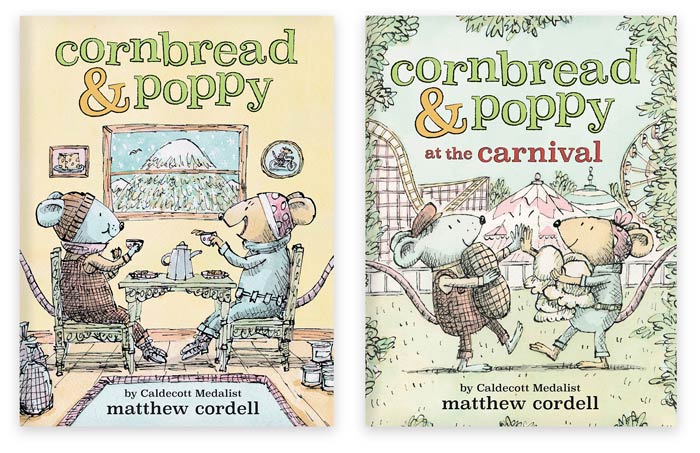

Your first early reader series debuts in January with Cornbread & Poppy (Little, Brown, 2022), a story about two very different best friends. Although the books in the series are packed full of wonderful illustrations, they also feature more text than your picture books. What was it like to create a different kind of book?

Writing, illustrating, and designing a book for a slightly older, more independent reader has been such a fun undertaking. I’m a big proponent of trying new things in life and in art. Whenever possible, it’s really exciting to put a new challenge in front of one’s self and see if we’ve got what it takes to do something new. And it breaks up the monotony of everyday life and work to try new things that we didn’t previously know or understand. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not about to go jump out of a plane, but I’ll certainly write a longer-format illustrated book for young readers!

I’m a big proponent of trying new things in life and in art.”

What would you like to tell your fans about your other forthcoming titles?

I’m currently working on the art for my next author/illustrator picture book, Evergreen. It involves a meek young squirrel who is asked to cross the forest alone for the first time in order to bring medicine to someone special who is very sick. It’s a lively character-driven adventure. I’m also illustrating a lovely picture book by Angela DiTerlizzi about bird migration (I’m a bigtime lover of birds and birding), and I’m illustrating a fun and madcap chapter book by Sara Pennypacker. Lots of plates in the air and lots of good times at the drawing table!

What are the best ways for readers to connect with you or to follow you on social media?

I’m pretty active and easy to find on social media. My preferred platform is Instagram (@cordell_matthew), followed by Facebook (facebook.com/cordellmatthew), and I’m on Twitter too (@cordellmatthew).