When people think of teacher librarians, our roles as advocates and fundraisers are not at the forefront. With this generation of digital natives, many think our students have no need for libraries. Consequently, there is a widespread belief that funding collection development is a waste of money. Even though academic and reference sources have moved to digital platforms, teens still prefer print books for their independent and pleasure reading. Readers of graphic novels prefer the experience of flipping through high-resolution images without having to scroll or resize pages to see the full layout and read the captions. What is more fun than learning to read backward through a hard copy of a manga title!

Though not a professional grant writer, I learned a few strategies that secured the support of a school board member for my library computer lab remodel, obtained funding from our school governance council for collection development, and raised funds for new books. The key is taking the time to research your collection and standards as well as the priorities of your audience. Your chances of getting the money you request are great if you are able to show evidence for specific needs, have achievable and clearly stated goals to meet those needs, and are able to match those needs with school, state, and national standards. While the need for books may be obvious to you, your school’s budget committee or outside funders likely have not thought much about how collections remain current and relevant or the cost of doing so. They will want to see, by using a strong visual presentation of the current collection and your goals, how their investment in your library will make a difference in student learning.

Research, research, research

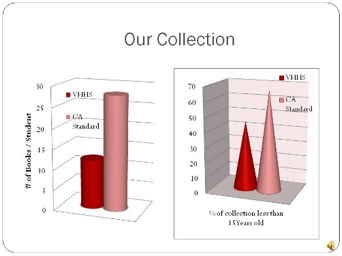

This what we do! Still, if your district is like mine, you have one teacher librarian doing the jobs of instruction, collection development and management, and clerking. Thankfully, many vendors, including Mackin, will allow you to upload your collection data and provide an in-depth analysis based on the standards you enter. For instance, I included the standards for age and number of titles per student to generate recommendations for which sections are most in need of weeding and updating.

Creating Goals and Context

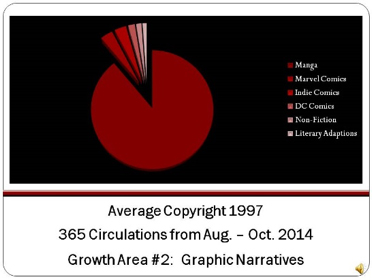

While it may seem self-evident to you that you simply need new books for the library, funders are more likely to give you money if you can provide them a specific list, with prices, and state why you need those books. For one of my MackinFunds fundraiser, I paired the collection analysis with circulation statistics to pinpoint areas of need. Though the entire collection needed updating, I targeted three areas: test preparation books, graphic novels and manga, and reading counts titles. All three had high circulation rates and old average publication dates to show need. They were also sections where the connection to student success and interest would be evident and the book wish lists would not need explanations for how they connect to the need.

Power of Visuals

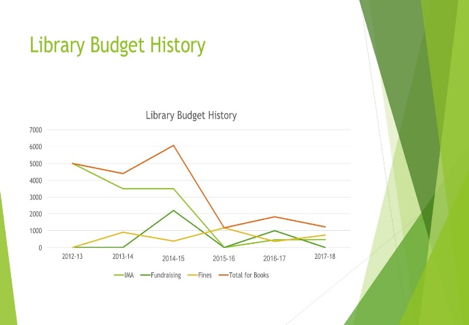

A visual presentation of data allows donors and decision-makers to quickly consider your evidence and to see the need more clearly. For the fundraiser mentioned above, I included graphs to show an overall picture of the library and to highlight the need in the targeted areas.

One program I used for this was Piktochart, though within spreadsheet and slide presentation software there are often tools that will allow you to make various charts and graphs using simple entry forms. Here is a chart I created in Google Slides to show a history of library funding.

Other times, photos may be used to create the story behind the numbers. For example, when I created a presentation to raise funds for the completion of our computer lab renovation, I relied on strong visuals to make my case. As you can see, I would not win any graphic design awards, so even simple designs with clear, relevant images and facts may be persuasive.

Be creative and persistent

Don’t give up if you get a rejection. Keep asking and keep looking for new sources. Mackin has a great database of grants. Ask parents, alumni, and community groups. Don’t be shy and don’t give up. Libraries are in it for the long haul, so remember even a year is not too long to invest in developing your proposal and soliciting funds. Once you put in the work the first time, each subsequent request may build off the work and research you already did. Additionally, you may gather new statistics to show the positive impact of funded projects. Again, this builds credibility that you and your library are trustworthy investments.