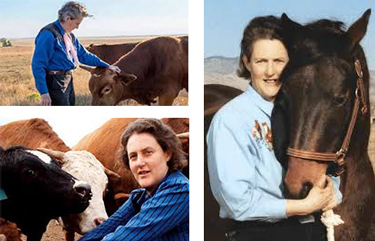

Temple Grandin, Ph.D., may be one of the most successful and visible professionals who is also on the autism spectrum. She is a college instructor, a highly sought after speaker, a well-respected consultant for the cattle and meat industry, a voracious reader, and a prolific author of journal articles and books. But her life’s path could have been so much different without the interventions and encouragement provided by her mother and educators.

“I was in third grade, and I still couldn’t read,” shares Grandin. “We were using the Dick and Jane books that were so boring. I hated Dick and Jane. My third-grade teacher called my mother and said, ‘We have to get Temple reading.’ So Mother started working with me.”

Not only did Grandin’s mother begin teaching her reading basics, she also created a special time and experience. “I was allowed to have a grown up drink of hot lemon water with a dab of tea. That was the only time I was allowed to have that—during reading time.” For about 45 minutes every day after school, Grandin and her mother focused on the tools essential to reading.

“Books were a very important part of my family. We would go to libraries and take books home. My mother read to my sister and me. Lots of times I couldn’t get to sleep at night, and Mother would say, ‘Read as late as you want, but stay on the bed and just have the reading light on.’ I’d stay up another hour reading.”

“Mother taught me to read with phonics, and we got a book worth reading: it was The Wizard of Oz (George M. Hill Company, 1900). First, she had me memorize the different letter sounds. She stuck the alphabet up on the wall, and she taught me the sounds and how to combine them and the rules. Then she started having me sound the words out. She would read a big part of The Wizard of Oz and then stop at an interesting part. I would sound out a few words. She started by reading about 95% and let me read some words. And she’d prompt me on some of the rules like ‘remember the vowel sounds long with the E on the end.’ These sorts of things. Gradually, we got to where I read everything. By the end of one semester, I was in sixth-grade reading.”

Grandin’s mother definitely understood the importance of reading at home. In addition to the reading lessons for Grandin, her mother would read to her daughters. “She read to us, and she read interesting old books like The Enchanted Island of Yew (Bobbs-Merril, 1903), one of L. Frank Baum’s lesser-known books. She even read some Oliver Twist (Richard Bentley, 1839) to us. She’d skip through the boring parts and just read the interesting parts. I grew up very much connected to books.”

“When I was a child right after the war, my father’s shirts went to the laundry and came back with poster board inside. I would collect those, and I had typing paper and a limited supply of art paper, crayons, thread, scotch tape, and half-inch adhesive tape. We also had a rag box. I would make all kinds of things out of these materials. Even though I came from a family that was well-off, my favorite things to play with were these simple things. I would make stuff. I would spend a lot of time getting things to work and playing and tinkering.”

Like reading, Grandin had to work at learning to write well. “I had teachers copy edit my work from a very early age. In my generation, teachers would mark it up and copy edit it and then have us correct it. I was a terrible student in high school. But by the time I got to ninth grade, I had better writing skills than some college students do today because my work would be marked up. Then I had to do my paper over. You learn not to have run-on sentences and things like that. When I went to college, I had to write a two-page paper every other week, and the teachers would mark it up and copy edit it. That’s how I learned how to write.”

“I’d like to see kids who are different not become their label. I’ve seen too many kids whose autism becomes their primary identity. The cattle pins in the movie are accurate, and I think that was important. I was identifying with the cattle industry and not with autism. Autism is an important part of who I am, but the cattle industry stuff came first.”

As a college professor, Grandin is working to help her students just as her instructors did for her. She teaches her students not only cattle-related coursework but also life skills to help them be more employable. “I can tell you right now, employers need people who can write a coherent report or memo. Basic writing skills are something employers need. But today we’ve got students whose writing skills are terrible. I have to correct grammar because they’ve managed to get all the way to graduate school and never once had a teacher copy edit their work and then have them correct it. I think it is definitely lacking in our education system.”

In addition to poor writing skills, Grandin has noticed students have deficits in other practical skills. “A lot of kids today are totally removed from the world of hands-on skills. They have really bad problem-solving skills. They have never learned to tinker and to learn from their mistakes. It is a serious problem.”

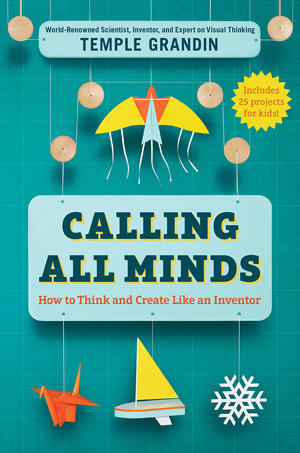

Grandin wrote Calling All Minds (Philomel Books, 2018) to help remedy the problem of poor problem solving and to get young people engaged with materials rather than electronics. “I want kids to just start making things, to learn how to tinker, and to learn from their mistakes. In Calling All Minds I have simple projects like making paper airplanes and snowflakes and making flowers with a compass. We’ve got to get kids off the electronics and get them out doing things. I’m not suggesting totally banning electronics. Let’s say they want to do one of my projects and then go to the Internet to look up some other things; I say fine. Limit it to an hour a day. You can’t spend four or five hours a day on a screen unless you are writing a paper. Limit time on screens for video games and social media.”

Grandin wrote Calling All Minds (Philomel Books, 2018) to help remedy the problem of poor problem solving and to get young people engaged with materials rather than electronics. “I want kids to just start making things, to learn how to tinker, and to learn from their mistakes. In Calling All Minds I have simple projects like making paper airplanes and snowflakes and making flowers with a compass. We’ve got to get kids off the electronics and get them out doing things. I’m not suggesting totally banning electronics. Let’s say they want to do one of my projects and then go to the Internet to look up some other things; I say fine. Limit it to an hour a day. You can’t spend four or five hours a day on a screen unless you are writing a paper. Limit time on screens for video games and social media.”

One positive aspect that Grandin sees in schools is the proliferation of Makerspaces. “Makerspaces are heading in the right direction. They are a really great thing that can be put together without a lot of money. It does not replace taking a class like welding or auto mechanics, but it is a step in the right direction. I definitely encourage Makerspaces. I went into two schools when I was doing a book tour for Calling All Minds, and they set up Makerspaces. We need to be encouraging that. We need to get kids hands-on.”

“Educators need to start looking at where kids are ten years after high school. If he went to college, he better not be in the basement playing video games. Because I’m seeing way too much of that. Too many smart, autistic kids, that is where they are ending up. They are in basements playing video games instead of building things in factories or designing airplanes or doing something useful.”

Grandin is passionate about emphasizing tinkering and hands-on learning because she believes those are avenues not only for learning life skills but also for discovering future careers in skilled trades. “There is a gigantic shortage of skilled trades right now. There is not enough respect for people who do these things. Kids who ought to be doing these trades, the ‘bad kids’ in school who are dyslexic, ADHD, or autistic, are often shoved into special ed because the schools took the hands-on classes out. Take kids with a label that are fully verbal. They usually have uneven skills—they are really good at one thing and really bad at others. We need to be doing more on building up these skills into something that could be a fulfilling career.”

Though Grandin continues teaching, consulting, and writing, she is now focusing the majority of her efforts on public speaking. At 71 years old, she is doing what she can to help young people, especially those with labels, find their career paths and be successful. “I’m doing a lot of speaking engagements because I think one of the most important things I can do is to get the kids that are different headed on the right track and get that fun welding job or some other good career. With my speaking engagement money, I have put about 20 graduate students through masters and PhD programs so they don’t have to pay gigantic debt.”

Though Grandin continues teaching, consulting, and writing, she is now focusing the majority of her efforts on public speaking. At 71 years old, she is doing what she can to help young people, especially those with labels, find their career paths and be successful. “I’m doing a lot of speaking engagements because I think one of the most important things I can do is to get the kids that are different headed on the right track and get that fun welding job or some other good career. With my speaking engagement money, I have put about 20 graduate students through masters and PhD programs so they don’t have to pay gigantic debt.”

A paperback version of Grandin’s Calling All Minds will be published Spring 2019. Says Grandin, “One of the reasons for Calling All Minds is to get parents and kids doing stuff. I just want to see this book get out there so kids can start making stuff and learning what an inventor is. An inventor had to tinker and a lot of those inventors were different kinds of people. I want to see the kids that think differently get out there and be successful.”