Parents and daycare providers know that kids love to hide. They crawl between table legs and piano legs, under the bed, in the closet, and behind the couch. They make forts out of blankets in the living room and tunnel through snow in the winter (which, in Minnesota where Mackin Books in Bloom’s librarians live, continues past Tax Day). And they build treehouses.

In her new picture book, Up in the Leaves : The True Story of the Central Park Treehouses, Shira Boss tells how her husband, Bob Redman, built his own hideaways in the trees of Central Park when he was a boy.

_________________________________________________________________________

Up in the Leaves is a personal story for us—it’s not often a non-famous person has a book written about his boyhood, or a writer can write a book about her husband! One of the themes of the book we’re most excited to share with children is marching to the beat of your own drummer and the exciting directions your life can take when you do so.

Growing up, Bob didn’t fit in with the mainstream of the city—he felt claustrophobic and uncomfortable in the crowds and even at school. He was smart and got good grades, but he wasn’t comfortable speaking up in class, even to answer questions. He was athletic, but he didn’t want to join teams. And while he loved learning, he didn’t want to go to college when it meant sitting in crowded classrooms and speaking up.

So, what was a boy like Bob to do?

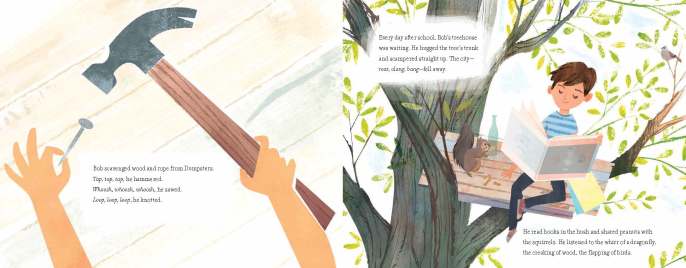

He retreated to Central Park and took refuge in the trees, and surreptitiously built treehouses high in the branches. Many kids love tree-climbing, and perhaps all covet secret hideaways. Bob took those childhood pursuits a step or two further, eventually staying overnight in the treehouses, and continuing to expand his treetop domains as a young adult.

When Shira reads Up in the Leaves out loud to kids and comes to the part where Bob’s mom gets worried about his future and tells Bob, “You’ll be grown up soon, you can’t stay up in trees!” she asks kids, “Can he stay up in trees?” Younger kids and dreamers call out, “Yes!” Some other kids side with Bob’s mom: “No!”

To Shira this is such an important moment: Can someone follow his heart, stay exactly where he wants to be, and end up making a living doing something he loves? (And for adults to ponder: How do we need to encourage and support children so that magic can happen?) It’s so fortunate that the Central Park Conservancy staff—when they finally caught Bob after 8 years of trying—recognized Bob’s potential. They noted his respect for trees—he hadn’t harmed the trees with any nails or other construction of his treehouses. And they were in awe of his tree-climbing abilities: an article in The New York Times quoted an authority as saying, “He walked up the tree. It was amazing.” They offered him a job, with on-the-job training.

Bob himself was amazed that such a career existed and that he really could stay up in trees! Today, he is one of the most respected arborists in New York City, known for taking the utmost care with cherished city trees heroically rooted in the urban landscape. He is also just as thrilled to be working in trees today as he was landing his first job in Central Park as a young adult.

Unfortunately, he had to stumble on this career path. Nobody in Bob’s life when he was growing up helped him think up ways his somewhat off-beat personality could be matched with a career. Instead of insisting he couldn’t stay up in trees, somebody could have explored with him ways he really could work outside or otherwise avoid the traditional, enclosed work spaces that he feared.

Our fervent wish is that children grow up with the confidence that they can find careers doing what they love, and that nobody has to feel pressured to “fit in” where he or she really doesn’t feel comfortable.

Using Bob as an example, it’s not just arboriculture that suited him. Putting together larger and larger treehouses, 60 feet off the ground, using rudimentary tools and salvaged materials? Clearly he became a skilled carpenter, and had a good understanding of physics and engineering to construct stable treehouses within moving branches. He could have pursued a career as a builder, even of private treehouses (which coincidentally has become wildly popular!).

And what about all those nights in Central Park spent star gazing? What started as a city boy’s dreamily staring into the heavens—itself a rare opportunity for a child growing up in a large city!—became more self-education, this time in astronomy. Bob subscribed to Astronomy magazine. He watched Carl Sagan’s series Cosmos with rapt interest. He regularly visited the Hayden Planetarium at The American Museum of Natural History one block from his home—that’s where he took his first look through a telescope and, amazed by what he saw, saved up for his own telescope. No adult recognized his interest or mentored him. That too did not turn into a career, although it was hardly wasted time. Nights spent under the stars resulted in a lifetime engaged with space and space exploration—our two sons have middle names after astronauts, and one’s first name is a crater on the moon. Bob sets his timer so they can all watch rocket launches together.

When Shira was introduced to Bob more than a decade ago, she was told that he is “a little odd” (and was told he “used to live in Central Park,” although there was no mention of his treehouses—she learned about those after meeting him and looking him up online!). Is he odd? Maybe so. He’s still shy and doesn’t want to be in a crowd or, worse, a room with other people. He doesn’t want attention. So we have picnics rather than eat at restaurants. As a family we tend to zig when others zag. Like many couples, we complement each other—Bob builds with the boys, Shira bakes with them. He climbs trees with them, she does art with them. He covers geology; she reads poetry.

Where we are the same is that we both love what we do for a living and don’t consider our jobs to be work but rather an opportunity to do what we enjoy and to be productive at the same time. We’re grateful our own kids have us as role models for finding careers that are a calling—and we hope that in reading Bob’s story in Up in the Leaves, children see that, yes, they can be different, follow the beat of their own drummer, and still fit into society even in unique ways.

We hope that teachers and librarians—so often the ones in children’s lives who are able to spark interests or provide a guiding light—will point to the book and Bob’s example as an affirmation that it’s okay to be different, and that each of us can find our happy path and place—in childhood and beyond.

And if parents find their children won’t come down from trees—maybe just let them stay. They might be climbers, architects, scientists, explorers—and best of all, content.

Articles about the Central Park treehouses:

The New York Times, September 27, 1986

People, November 10, 1986

The New York Times, September 10, 2000

_________________________________________________________________________

From the publisher:

Shira Boss is a writer who lives on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, three blocks from Central Park. Up in the Leaves is her second book. She earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from Columbia University, including a master’s in Journalism. When her Japanese maple tree needed pruning, several people suggested she call arborist Bob Redman. He said it was the smallest tree he had ever worked on (about four feet high, in a pot). Now they have two sons, two whippets—and many more trees.