Sophie Blackall is the recipient of the 2016 Randolph Caldecott Medal—one of the most prestigious honors an illustrator can receive. She is also a mother, author, researcher, advocate for measles prevention, and so much more. In this piece, Blackall shares a bit of her past experiences and present activities with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler.

TAKING A LOOK BACK

It seems that childhood plays such a significant role in shaping a person’s future. What was your childhood like?

like?

I was lucky enough to grow up in a house filled with books. My mother encouraged us to read, and my brother and I learned from a young age that we could get out of chores if we buried our noses in books. Now that I think about it, my own children are equally crafty.

With reading so encouraged in your home, surely you had a favorite book. Do you recall what it was?

The first book I bought with my own money was Winnie-the-Pooh (Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1926). I was seven. It was an old, worn edition–a prop in my mother’s antique shop. I read it in my secret spot under a table. I used to hide the book so nobody would buy it. Eventually my mother sold it to me for a dollar, and I polished the steps to earn the money.

What made Winnie-the-Pooh so special for you?

I had never known a book like it. A book with interjections and digressions that meandered and backtracked, that bounced and hummed, that drew you in so close that you felt you were in the very forest itself, and at the same time allowed you to step back and see the  actual form of a book. With characters so endearing you hated to leave them behind. It is still one of my favorite books of all time, and I still have my old copy.

actual form of a book. With characters so endearing you hated to leave them behind. It is still one of my favorite books of all time, and I still have my old copy.

Clearly, reading was important in your family. So, when did you begin to draw?

I grew up in a small country town, and my brother was enlisted to walk me to elementary school each morning. But in the afternoons we struck a deal: he ditched me in favor of fishing for yabbies (Australian crawfish) in the creek with his friends, and I was free to wander home the long way, past the butcher’s shop. I’d stick my head in the door, the butcher would roll up a few sheets of paper for me to draw on, and toss a slice of bologna into the bargain. I’ve always been fond of butchers. My other free canvas was the beach. I would draw for hours in the sand with a stick, and watch the tide wash it all away.

Beyond encouraging reading and selling you your first book, what did your parents, teachers, and/or librarians do to encourage your developing interests and skills?

When I was about 12, I received a box in the mail from my father, who lived in another state. It was a box of books—reproductions of English Victorian children’s books—each one in its own slip case, ranging in size from a grand 14-inches tall to a tiny three inches. With color plates protected by glassine paper, and ribbons to mark your page. I don’t know how he knew this would appeal to me more than a Duran Duran record, but it was kind of life-changing. With this gift I fell in love with books as objects, and ever since I have been drawn to 19th-century illustration.

TAKING A LEAP OF FAITH

You live in the United States now, but you were born and raised in Australia. When did you move and why?

My then husband and I won green cards in the lottery and we arrived in New York in 2000 with two children under three, a couple of suitcases, a coffee pot, a bunch of books, and my watercolors. We didn’t know a soul.

It seems like moving to a new country without having any connections would be a difficult and lonely transition. What was it like for you in your new home?

The first winter was tough; we rented a one-room apartment overrun with mice, lived on Goya beans, and spent many, many hours at the Brooklyn Public Library, where my son learned to walk. And then spring came, and with it a commission from the New York Times, and our three-year-old daughter, by far the most charming member of the family, recruited friends in the park. That was 16 years ago.

So the New York Times was the first to publish your illustrations, but how did you break into the book industry?

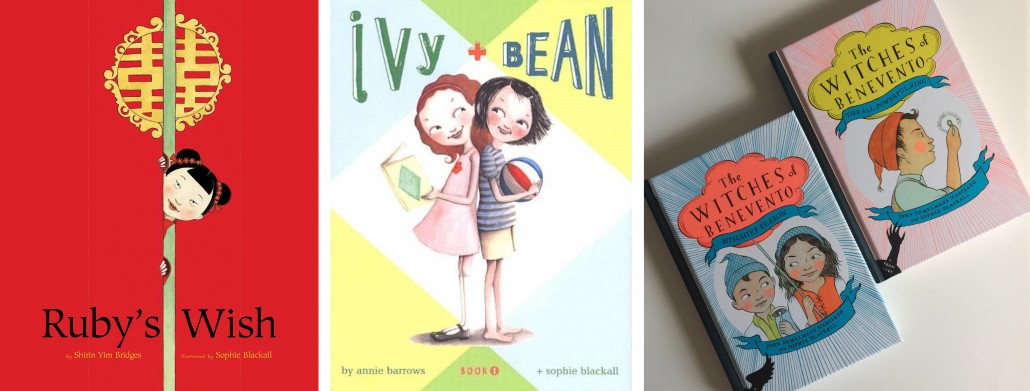

I traipsed the city with my portfolio, visiting publishers, and got many polite, encouraging rejections for my efforts. And then one day Chronicle Books offered me a chance to do a test illustration for a picture book, kind of like a bake-off. The book was Ruby’s Wish (Chronicle Books, 2002), by Shirin Yim Bridges, which went on to win the Ezra Jack Keats Award for both writing and pictures. I am full of admiration for every editor who ever took a chance on a new illustrator–in my case, Victoria Rock at Chronicle. It is a leap of faith and I think I can speak for all illustrators when I say we are so grateful for that trust.

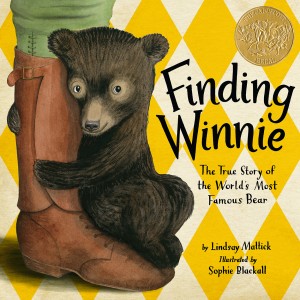

As you mentioned, your first book received the Keats Award. Many of your subsequent books have been award winners, and now one of your latest books, Finding Winnie (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2015), just won the 2016 Caldecott Medal. It seems like everyone who has received the medal has a special story about the call. What is yours?

As you mentioned, your first book received the Keats Award. Many of your subsequent books have been award winners, and now one of your latest books, Finding Winnie (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2015), just won the 2016 Caldecott Medal. It seems like everyone who has received the medal has a special story about the call. What is yours?

blockquote>“Within the pages of a book our favorite places and beloved characters will always be there waiting.”

In the weeks and days leading up to the announcement, I tried very hard to banish all thought of the Caldecott from my head. But it kept creeping back in. I wrestled with it all weekend. “Who are you to hope?” I asked myself, in Maggie Smith’s most withering voice… and then I imagined getting the call, imagined every detail. When I imagine something, it usually ends up in a drawing, not as a reality. I was pretty sure that the very act of imagining it was enough to prevent it from coming true. In my sleeplessness I should have picked up an old friend of a book, but instead I wandered the Internet, fueling the fire.

“When we don’t pay attention to details, our books suffer and our readers lose faith.”

And then I read some things which helped enormously. The first was Kimberly Brusker Bradley’s blogpost. “I want to win the Newbery so bad it makes my teeth hurt,” she wrote. “And yet, it doesn’t really matter at all. Both of these things are absolutely true.” And this made me realize there’s nothing wrong with hoping. The second was Susan Kusel’s post, which reminded me that whatever happened was out of my control, and unpredictable, and whether I hoped, or fretted, or slept like a cat, it wouldn’t make a jot of difference. Her words gave me enormous confidence in the process and the committee. I don’t envy their task, but I have such respect for their commitment and patience and attentiveness and open mindedness and willingness to work together. I realized that they would choose the right book, whichever book that happened to be.

And so I went to sleep. I’m lying. I didn’t really sleep at all…

I’d heard the call usually comes before 6:30am. So by 6:31am, I’d resigned myself that it was not to be. I hopped in the shower; made my son’s school lunch. Told my partner we could relax. It wasn’t going to happen. We had a lovely sad-happy moment of realizing that Caldecott or no, we were very lucky people indeed.

And then the phone rang.

The rest is a blur. I think my legs gave way. I may have sobbed. It’s still utterly surreal that your life can turn around in a span of minutes. It will take a lot longer to adjust to the idea that my name falls at the end of this list of luminaries: Virginia Lee Burton. Maurice Sendak. Ezra Jack Keats. Barbara Cooney. The Provensons. Paul O. Zelinsky. Wiesner. Selznick. Pinkney. Stead. Raschka. Klassen. Floca. Santat.

I’m so grateful to the committee. The sound of a room of laughing, cheering librarians coming down the wire will stay with me forever.

Your Caldecott acceptance speech really seemed to emphasize the power of story. Why do you believe story is so important? How have you personally witnessed this power’s effect on others?

I really love doing school visits. One day I gave a presentation to a large and rowdy group of kids. I went all out.

- I explained how to make a picture book.

- I drew for them. Upside down. With Chinese ink.

- I showed them whisks from four centuries and how you can paint with squished blackberries.

- I took them on a journey to crowded classrooms in Congo and to a school for five in Bhutan on the top of a mountain.

- I told them what it was like to watch kids in Rwanda open a book for the very first time, and how little children walked for miles to a hilltop, where village elders told stories passed down through the ages.

At the end I opened it up to questions. A girl shot up her hand.

“Can you tell us a story?”

“A story? After all that, you want a story?”

“Yes!” came the resounding cry.

And so I pulled up a tiny chair and read from the proofs of Finding Winnie, which was not yet a proper book. You could have heard a pin drop. The principal came in half-way through and wiped a discreet tear. The teachers wept freely and reached for tissues.

I have read the finished book often since then, and almost every time I get to the end, a kid will ask, “Is Harry still alive?” even though they know the story took place over a hundred years ago. And then, immediately after, “Is Winnie still alive?” and they are crestfallen to hear she is not, because somehow they know people get old and die, but they want bears to live forever. And occasionally I tell them that Winnie’s skull is on display in London and her teeth are rotten from all the condensed milk, which is true and fascinating and slightly unsettling, like lots of the things I like, but usually we talk about our own stories. How we go about our lives, gathering stories … to tell our families over dinner, or collecting stories from our evenings to tell our studio mates at lunch. How our stories intertwine and overlap. How we are part of other people’s stories as they are a part of ours, no matter where we were born, who we are, or where we live, and how we pass those stories down through the ages. How sometimes we have to let one story end so another can begin, like when we move houses, or grow up, or lose someone we love. But how we will always have those stories to revisit and reread. Within the pages of a book our favorite places and beloved characters will always be there waiting.

TAKING ON NEW TASKS

“Beloved characters” immediately brings to mind Ivy and Bean. What an amazing series! And your illustrations just capture their expressions so well. What are these characters doing these days?

When we began work on Ivy and Bean (Chronicle Books), Annie Barrows, the author, Victoria Rock, the editor, and I each had a seven-year-old daughter. Those three girls are now sophomores in college. I meet kids at book stores and festivals who grew up with Ivy and Bean. It simultaneously fills me with joy and makes me feel really old.

“I believe children who are eager to read about their world should be rewarded with honest, thoughtful books.”

I am very proud to be working with UNICEF and the American Academy of Pediatrics on a nationwide campaign called “Ivy and Bean vs. The Measles” which helps explain how safe and easy and important immunization is for our children. Ivy and Bean are great advocates. I almost forget sometimes that they’re not real.

You have worked with many different types of book formats, from flap books to collaborations to picture books. How do you choose which projects to work on?

When it comes to choosing a project I look for something which makes my heart skip a beat; a story which forms pictures that I can’t ignore. When editor Susan Rich first wrote to me about Finding Winnie, I had just told my wonderful and wise agent Nancy Gallt, “Don’t let me take on any more books just now. Seriously. Even if I tell you this one is a find. Remind me that I haven’t had a weekend off in a year. That my children are withering from neglect. That I ought to be going to physical therapy.”

But Susan’s email was so seductive; Nancy’s best efforts were a lost cause. I was a love-struck sailor hearing the siren’s call. I once told my family I would sail off into the sunset with Susan Rich. They refer to her simply as “Sunset.” The thing about Susan, apart from her wit, genius, humanity, grace, and humor, is that she has a fantastic voice. I would answer the phone and an hour later we would have covered trim sizes and train journeys, soldiers and serendipity, beloved, bedraggled toys, and the contents of preschoolers’ pockets.

Finding Winnie was an extraordinary collaboration. Susan and I and the whole Little, Brown design team solved problems and shared stories and navigated every twist and turn together. Another collaboration which is making me very happy is The Witches of Benevento (Viking), a series of chapter books I’m working on with my studio mate, author John Bemelmans Marciano. This is unlike anything either of us has done before. Mostly authors and illustrators have little interaction, but we are working on every aspect of the books together, which means long hours at our local pie shop as we cut and paste text and debate our characters’ attributes, and share research and plan trips to Italy. I know, it sounds terrible. The books are set in 1820s Italy, in the town of Benevento, famous for its witches, and the stories revolve around five plucky, curious, brave, hilarious children.

Sophie with children from Bhutan

Children in Rwanda reading their first book

Bhutan’s School for Five

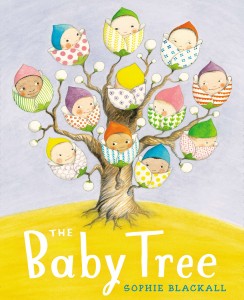

What is the story behind The Baby Tree (Nancy Paulsen Books, 2014)?

On a train many years ago, I heard a small boy ask his mother, “Where do you get babies?”

“Oh” she said, looking about desperately, “You, um, well, you know, you … plant a seed and well…”

“Babies grow on a tree?”

“Sort of” said the Mom. “Look! It’s our stop.”

I wanted to pull that boy aside and say, “Listen kid, here’s what really happens.” Instead I wrote The Baby Tree, explaining where babies come from, which was published by Nancy Paulsen, and which, I’m proud to say, is now in 14 languages.

But I had one angry email from a parent whose 10-year-old child checked the book out of the library and then asked her questions she wasn’t ready to answer. I believe that if a child is old enough to read The Baby Tree on his or her own, and curious enough to continue to read beyond the end of the story to the back matter–which contains answers to further questions about where babies come from, and is designed to look a bit boring and definitely not part of the story–then that child has a right to the information. There is nothing salacious or untrue in the book, and the answers to the most common questions children ask about reproduction are given in a simple and straightforward way.

As the author Ellis W. Whiting wrote in the introduction to his 1933 book, The Story of Life (Story of Life Publishing Company, 1954), designed to be read to children of four or five and for older children to read themselves, “It is important that the first picture of sex knowledge which passes through the ‘lens’ into the child mind is a correct one.” If the correct information is not available, then that picture will be readily supplied from another source, “the half-informed, misled playmate.”

The story of The Baby Tree is essentially a child’s quest for information. I believe children who are eager to read about their world should be rewarded with honest, thoughtful books.

“This is a wonderful era in children’s publishing. The movement for increased diversity in every aspect of the business has been long overdue and is very welcome.”

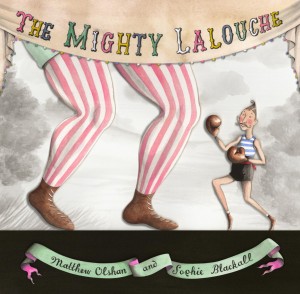

In addition to providing solid information in your writing, your illustrations are also very detailed. It seems that you really do your homework, if you will. Examples I can cite, include: the rocket car in The Mighty Lalouche (Schwartz & Wade, 2013), the snake tied in a bowline knot and a clove hitch in The Crows of Pearblossom (Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2011), and the photographs referenced in Finding Winnie. Is research important for illustrators?

I think research is incredibly important, and luckily it’s one of my favorite parts of the whole process of making a book.

When I was working on Finding Winnie, I traveled to England. I rummaged in the archives of the London Zoo, where I reveled in The Daily Occurrences, the zookeeper’s handwritten record of comings and goings, in which I read that the day Winnie arrived, it was foggy, a white-whiskered swine was unwell, and at 7am the temperature in the Hippopotamus House was 54˚. At the War Museum, I learned that in WWI, Canadian soldiers were issued boots with cardboard soles which disintegrated in the mud of the Salisbury Plain where it rained and rained and rained. These details didn’t make it into the book, but I know they are there, under the surface.

When I was working on Finding Winnie, I traveled to England. I rummaged in the archives of the London Zoo, where I reveled in The Daily Occurrences, the zookeeper’s handwritten record of comings and goings, in which I read that the day Winnie arrived, it was foggy, a white-whiskered swine was unwell, and at 7am the temperature in the Hippopotamus House was 54˚. At the War Museum, I learned that in WWI, Canadian soldiers were issued boots with cardboard soles which disintegrated in the mud of the Salisbury Plain where it rained and rained and rained. These details didn’t make it into the book, but I know they are there, under the surface.

I don’t think research should be limited to non-fiction or historical fiction. Anything we put in our books, any character or setting, any object, should be there for a reason and should be rendered thoughtfully. I once saw an illustration in a book where the legs of a chair didn’t appear to meet the ground. It was not a book about a floating chair. In another, the character’s shirt had six stripes on one page, and seven on the next. A friend mentioned reading a book with a Chinese character who had been given a Japanese last name. It’s hard to stick with a story after that. You can’t quite trust it.

These might seem like trivial transgressions. “Kids won’t notice!” we might think. Oh, but they do. So we must try. We will no doubt make mistakes but we’ll do our best to learn from them. When we don’t pay attention to details, our books suffer and our readers lose faith. So we must look closely at chairs, and research our cultural references, and spend as much time as possible with real children.

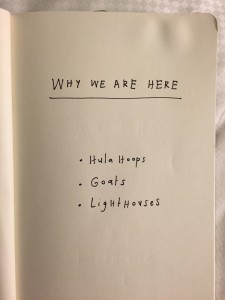

Do you keep an ideas journal? Do you have a system for storing and/or organizing your thoughts?

I rotate a lot of different bags—they live in a heap in the vestibule, it’s a bit of an issue—and I keep a notebook in every bag and they are all full of lists. Sometimes a bag falls out of favor and the notebook with it, and when I return to it after some time, I have no idea what I was thinking. For instance:

WHY WE ARE HERE

- hula hoops

- goats

- lighthouses

But if I look at the trail of work in the intervening years, I can actually see drawings of hula hoops, and goats, and lighthouses.

What is your workspace like and what do you appreciate most about it?

I’m fortunate to live in Brooklyn which has a disproportionate population of children’s book makers, and even more fortunate to share a studio with some of the best of them: Brian Floca, Edward Hemingway, John Bemelmans Marciano, and Sergio Ruzzier. I know my work is better for their company and I know how lucky I am.

From: left to right Brian Floca, Sergio Ruzzier, Sophie Blackall, Edward Hemingway and John Bemelmans Marciano

We share not only the physical space–a grimy loft in an old factory near the stagnant waters of the Gowanus Canal–but also our ups and downs, advice, and gossip. We share reference books, recipes, long nights, pen nibs, outrage, archives, painkillers, dark chocolate, sightings of our resident kestrel, and almost every day, lunch. We were together when the Caldecott award was announced and they were all there for the ceremony. I wouldn’t be here without them.

DREAMS AND ASPIRATIONS

I was one of those people who were certain at an early age what they’re going to do. Apart from a brief flirtation with wanting to be a chef or a nurse, illustrating children’s books was the goal. Having said that, I still harbor desires to do other things as well; I want to dress windows and design clothes, raise ducks, and tend a lighthouse. There are never enough hours in the day.

DIVERSITY AND AUTHENTICITY

As an illustrator, it’s my job to reflect the world to the best of my ability. My kids have been fortunate to attend incredibly diverse public schools in New York, and reflecting that community in my picture books has always been important.

I’ve been trusted to illustrate manuscripts from authors of color and have taken that responsibility very seriously. Having said that, the way we look at pictures is incredibly complicated. I cannot ensure my images will be read the way I intended, I can only approach each illustration with as much research, thoughtfulness, empathy, and imagination as I can muster.

I learn from every book I make but I’m sure I haven’t made my last mistake. I hope, though, to avoid the fear of making new mistakes, a fear which can lead to creative paralysis.

This is a wonderful era in children’s publishing. The movement for increased diversity in every aspect of the business has been long overdue and is very welcome. I’m sure we’ll make more mistakes and have more heated debates, but the end result will hopefully be better books for all children. Books which make kids laugh, and make them think, which show children the world and let them recognize themselves. And books which make them want to keep reading.

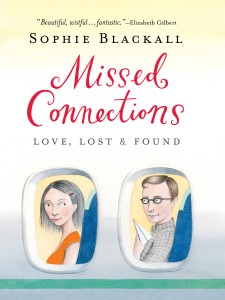

MISSED CONNECTIONS AND DESTINY

I was on a subway train about seven years ago, squished in the rush hour crowd when a handsome chap squeezed in next to me. We apologized in rounds and when he stepped off he appeared in the window and mouthed two words. I turned to the girl next to me.

“What did he say?”

“Missed Connections,” she said.

I had no idea what she was talking about but I didn’t want to seem uncool, so I made a mental note; when I got home, I Googled it. (I didn’t have a smart phone back then.) Here is the Missed Connection post I read on Craigslist:

You had a guitar, I had a blue hat – We exchanged glances and smiles on the subway platform. I pretended to read my New Yorker but couldn’t concentrate. You got on the Q and I stayed to wait for the B. You were lovely. You probably won’t read this, but I thought to try.

In the space of eight seconds I had experienced love, loss, and regret. I held my breath and clicked on the next post. And the next. And the next. It was dark long before I tore myself away. Missed Connections were bountiful. They appeared faster than I could read them and I didn’t even have to leave my desk to find them.

Then I saw the posts had a limited lifespan. They dropped off the site after a week, gone forever. I went into a slight panic. I started gleaning in earnest and archiving. I figured out how to set up a blog. I painted the guitar and blue hat. I kept gleaning. I kept painting and posting and gleaning. I didn’t tell anyone. I didn’t really think anyone would read it.

Then a strange thing happened. I started getting comments. They came in thick and fast, people wrote about the pictures and posted them on their own blogs. Emails came from Greece and Saudi Arabia, from the Netherlands and New Zealand and Hong Kong. Magazines asked for interviews, the New York Times called. And regular people wrote begging me to help them to find their lost loves. And told me these pictures had made their day, had pulled them out of a funk, had put a spark back in their marriage, had given them hope—hope in kindness and intimacy between strangers, hope in finding their own true love, hope of connecting.

People close to me—sensible, business-minded people—suggested I should not be putting my work up like that on the Internet. That I should be holding back and putting together proposals for publishers, that no one would want to publish something that was already available for free. It turns out they were wrong. In the end, 12 different publishers asked for Missed Connections (Workman Publishing Company, 2011).

The book led to a poster for the New York City MTA, which was seen by a consultant for the UN Foundation, who wrote to me asking if I might be interested in traveling to the Democratic Republic of Congo to visit measles-affected communities and then to make some posters to try to convince people to help eliminate this disease, which kills over 400 children a day. I read the email on my phone just before take off on a Cincinnati runway. It had never occurred to me to visit Congo. I wasn’t even entirely sure I could place it on a map. But I could hardly wait to land in New York so I could reply.

In spite of reading terrible news every day from Central Africa, and in spite of my father’s subsequent thoughtful links to reports of Congolese plane crashes, there were three insistent reasons to go:

- I had never been to Africa.

- I could hear all the news and all the statistics about measles, I could read that 400 children die a day, and yet, as I waved my own healthy children off to school in the morning, I couldn’t possibly imagine the truth of this until I saw it.

- I love my work. I love making pictures that encourage children to turn pages or that cheer up subway commuters, or pictures that remind people they might fall in love at any moment, but I had never worked on pictures which might conceivably save lives.

The measles project led to further work with UNICEF and Save the Children, which has taken me all around the world, to densely crowded dirt floor classrooms in Congo and a school in Bhutan half-way in the sky, where the student population is five and the commute is a two-hour vertical climb. In India I saw kids playing their version of Red Light, Green Light, a game I played as a child in Australia, a game my kids played in Brooklyn. And in Rwanda I watched children who had never seen a book before, hold one in their hands. A book written in Kinyarwanda, illustrated by a local artist. With my heart in my mouth, I watched them turn the pages and look at the pictures and make out the words. It wasn’t that Rwandan children weren’t learning to read, they were, just from dry sentences on blackboards to be read in unison. Compare that with being able to open a book, to step into another world, to see the sea for the time, or outer space, or to read a story about a family just like theirs.

So I rode the subway, made eye contact with a stranger, and ended up in Rwanda.