If you speak with Ashley Bryan, it is difficult to believe he has seen more than nine decades of life. Though his age suggests an elderly man in his golden years, Bryan’s passion for art and excitement for life reveal a man filled with childlike wonder eager to experience each new day. An award-winning author and artist, Bryan is best known for his work bringing African folktales and spirituals to life. Bryan has also written and/or illustrated picture books and poetry anthologies. Here Bryan shares with Mackin’s Amy Meythaler stories from his life, why the multiculturalism discussion is essential, the importance of education, and the power of perseverance.

Cultivating A Creative Spirit

As humans, we tend to like categories when making sense of the world around us. With that in mind, what do you consider yourself? You draw, paint, make puppets, tell stories, write poetry, compile books, create stained glass, and more. Are you an artist? An illustrator? An author? A poet?

To me there are no categories. I think we are all many things. I am always working along with what I do in the same way I feel other people are. They may not consider themselves artists, but they all have the aesthetic in them. It is international. There is no person in the world without an aesthetic component—a response to what is lovely and beautiful or what is recreated in a different way. We are all recreating things in our own way.

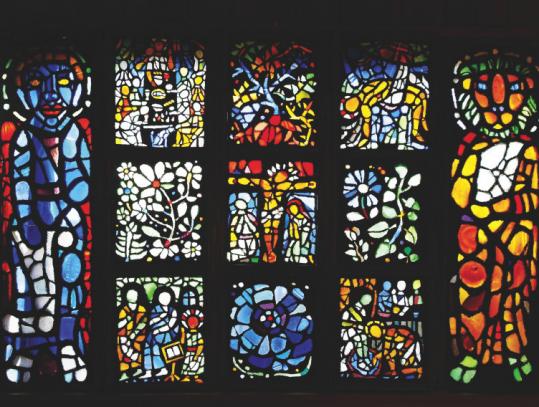

Detail of Ashley’s stained glass

Ashley created this stained glass window depicting five scenes from the life of Jesus.

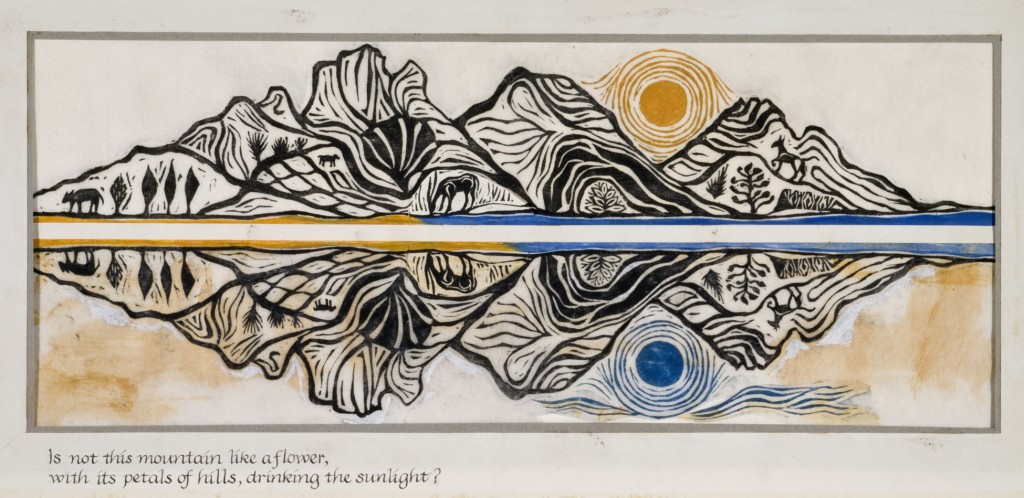

Ashley Bryan, Mountain View, 1967, from Moon, for What Do You Wait? (Atheneum, 1967), linoleum print, 16 ½ x 8 in.

When did you begin creating or recreating things in your own way? Do you remember your first experiences with reading, writing, and drawing?

From the time I was born, I’ve been drawing and painting and writing and reading. I remember when I was little I would see my parents sitting and writing a letter, so I would take a paper and I would write. I would say, “I just wrote a story, now read it to me.” And they would say, “Oh, that is scribble scrabble.” I had to interpret it for them because they couldn’t read it. But I knew I was doing what they were doing because I took the pencil and I was writing on the page. I was always doing these things.

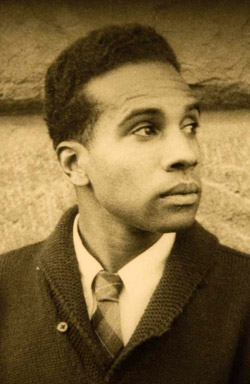

Ashley as a young man

Your parents were very supportive of your artistic endeavors. In fact, they brought home a little desk so you would have a place to work and made sure you had opportunities to learn art and music.

I was always fortunate being encouraged at home by my parents and also by my teachers at public school in New York City during the 1920s and 1930s.

I grew up during the Great Depression years, but I was always drawing. Why? Because there was the free Works Progress Administration (WPA) founded during the Depression by the government to employ artists and musicians in communities throughout the country. And my parents sent their six children, and the three cousins my parents raised after my aunt died, to these free classes in music and art. We all learned to play instruments. We were all drawing and painting. These things had nothing to do with what we would become in life. It had everything to do with being human.

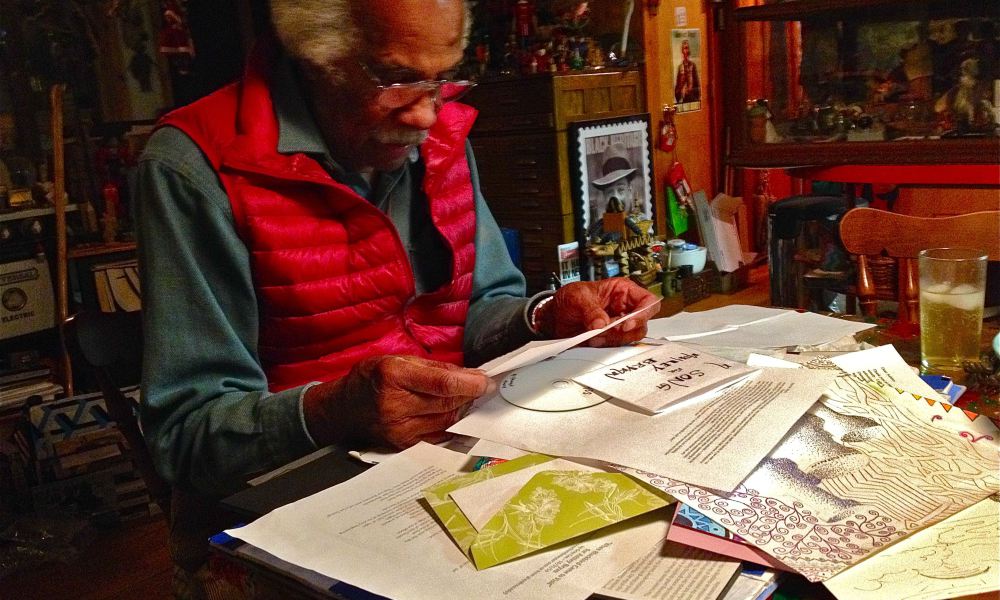

Ashley working in his studio

You said your teachers were very encouraging. What roles did they play in developing your interests and talents?

When I was in kindergarten, we learned the letters of the alphabet. The teacher asked us to draw a picture for each letter. When we had completed from A to Z, the teacher gave us colored paper and we sewed the pages together. Then the teacher told us we just published an alphabet book. Imagine that! In kindergarten I was the author, the illustrator, and the book binder! The teacher told us to take the book home and then we would be book distributors as well.

The teacher later asked what happened when we took our books home. I said that my mom hugged and kissed me and my dad picked me up and spun me around. Everyone else had excited responses, too, and the teacher said, “Oh, you were getting rave reviews for those limited editions of one-of-a-kind books! We will keep on publishing books.” So when we learned to spell words, we did a word book. And when we learned numbers, we did a number book. We learned sentences and made sentence books.

“You must wake up as a child. You must wake up with the feeling of curiosity and adventure that [a] child faces when awaking.”

These were my first published books and I never stopped.

From kindergarten to high school, all my teachers in New York City were white and they all encouraged my talents through the years. They gave me all kinds of materials during the Depression years so that I could continue to grow in my love of art. And when I was in high school doing my work, I was supported by my teachers there.

To have that insight to open up the excitement of learning is the genius of our teaching profession. That is the important thing: to encourage a child. That is what we grow on, encouragement. It is very difficult to grow when you are not encouraged or you are put down as a child. When a child is doing something creative and is told “You are no good at that” or “You will never be good at that,” it is very difficult to persist. But if you are encouraged, you go deeper and deeper into it, and it becomes a part of your life.

Overcoming Obstacles

Clearly your primary and secondary school experiences deeply impacted you. What were your college years like? Was college as positive as your earlier education?

When I graduated, I knew I wanted to go to art college. But with five siblings and three cousins in my home, I knew there was no way that I could go without a scholarship. My teachers helped me prepare a very strong portfolio, and I made the rounds to the top art schools. I was told it was the best portfolio they had seen but it would be a waste to give a scholarship to a colored person. This was in New York City in 1940.

I could have given up, but I didn’t. I went back to my high school. Now the teachers knew I was black and I knew I was black, but they said, “Ashley, come back. Work on the yearbook with us and do more for your portfolio if you’d like, but in the summer you take the exam for the Cooper Union School of Art and Engineering. They do not see you there.”

In 1940, the Cooper Union exam was given in the Great Hall where all of our presidents have lectured. It was a college founded in the 1850s by Peter Cooper offering free tuition in art and engineering studies for men and women. And in that exam you got a bar of Plasticine clay for an exercise in sculpture. They also noted an exercise for drawing, and they noted an exercise for architecture. You put your answers on the tray with your name and address, and then put your tray on the platform of the Great Hall and left. The next day when the professors came down, they selected those to enter the Cooper Union School. I was one of those chosen.

I was the only black in my class, but it enabled me to go further in my studies. And the students in that class became my friends for life. A number of them followed me until their deaths and those two or three that are still alive I am still close to. But it enabled me to go further so it always meant so much to me that college was free.

“And it is because of the diverse contributions that we have an American culture. It is very important that that be part of every child’s study. It does not matter who is in your class. It does not matter if you are in an area with one unified group. Learn about the people who make up the country in which you live. It is vital, it is important.”

You mentioned that you could have given up when you were denied a scholarship because of your race. Why didn’t you give up? Why did you refuse to be defeated?

Art was a field where blacks were not really accepted, and it would not be a likely field for employment. I could have decided to work in another area or a profession that might have opened up to me. It is just that I had a desire to grow as an artist and I persisted. And it was of course the encouragement of my family, my teachers, my friends; they all looked upon me as one who was very gifted in what I was doing in art. And they encouraged me.

People generally give up when they meet with hardships like color even though they may have a talent. How one persists despite obstacles is always inspiring to me.

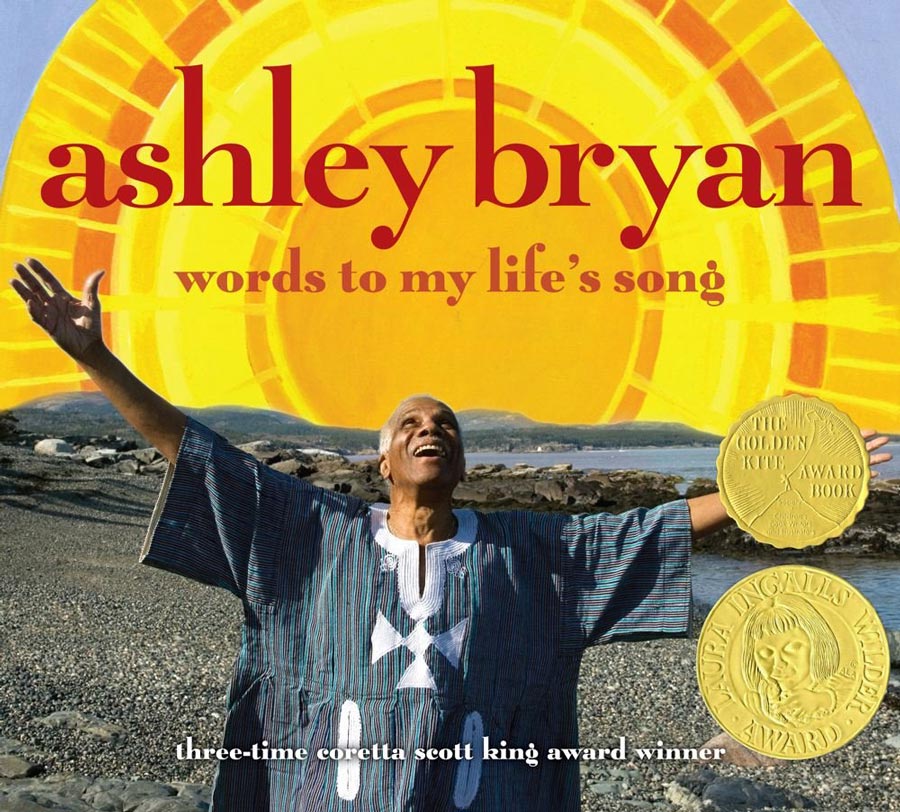

When my publishers asked me to write an autobiography, I said, “But all of my work is my autobiography.” They said, “No, we mean we want something for children about how you persisted despite obstacles.” I said, “You want me to write everybody’s story? Because no one gets anywhere without overcoming obstacles.” I always hope when people read my book Ashley Bryan: Words to My Life’s Song (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2009), that they will see their own lives and the obstacles they have faced in realizing what they are doing and who they are.

When my publishers asked me to write an autobiography, I said, “But all of my work is my autobiography.” They said, “No, we mean we want something for children about how you persisted despite obstacles.” I said, “You want me to write everybody’s story? Because no one gets anywhere without overcoming obstacles.” I always hope when people read my book Ashley Bryan: Words to My Life’s Song (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2009), that they will see their own lives and the obstacles they have faced in realizing what they are doing and who they are.

I tell second- and third-grade students that you can’t go into the third, the fourth, the fifth grade if you don’t overcome the obstacles. Those are the challenges. If there are no challenges, you give it no thought. But it is only when you are challenged that you grow and progress. And if you meet a challenge and decide it is too hard and you’re not going to do it, you are missing an opportunity of growing, of learning, of strengthening, of becoming more of a person. So even if you fail, you’ve learned so much from that effort.

Sharing Talents

You are a highly educated and well-traveled man. In the middle of your education at Cooper Union, you were drafted into the army. Even during your time serving in World War II you continued your education. Following your graduation from Cooper Union, you studied at Columbia University, Aix-Marseille Université in France, and the University of Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany as a Fulbright scholar. Why was pursuing further education so important to you?

It was important to me to study. It was the art instruction that I was seeking, and then in literature and in languages, too. Because I know whatever you bring as a teacher will give a source of body to whatever the theme you are teaching. It was important for me to be excited about whatever the challenge would be. So if I was teaching a class in drawing or design or painting, all that I had been working with fed into that.

I believe the excitement that a teacher feels is what the student is tapping into. If the students feel the teacher is excited about what he or she is sharing, and is not just in it because he or she is being paid to teach the course, they often tap into it. They may not become sociologists or dancers or singers, but they will have felt inspired by the excitement of what the teacher is sharing.

During and after your own studies, you taught art to students both informally and formally. Why did you go into education? When did you know you would teach?

When I was growing up, in my community near the elementary school there was a great big church, a German Lutheran church. I told my mom that I wanted to go to that great big pretty church with the bells that ring and the pretty windows, so my mother took me. It turned out that I was the first black to enter that church—St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Bronx.

When I was about 12 or 13 years old, the church leaders at St. John’s said to me, “Ashley you have a talent. You must therefore share it. We will give you the room and the materials and you will have classes in drawing and painting for the people of the community, the children and all.” And that is how my love for teaching started. I found right off that I loved sharing what I enjoyed doing in the arts with others, so I knew that teaching would be an area that I would always be involved in.

When I was to be employed later, it was in the teaching of art that was a natural fit to me because it was the area in which I had the most to give. And it was that training from the church—you have a gift, you must share it with others—that I learned you don’t hold onto what you have.

“I infuse my prose with poetry—with the rhythms of poetry, the sounds, the beats. That is a challenge to find a way in my writing to open up the spirit of the voice, to express the sound of the voice in the printed word. That is what has excited me.”

Discovering New Directions

How did you eventually find your way into the publishing world? Did you find immediate success or were there obstacles to overcome?

When I was a student at Columbia studying philosophy, I decided to show my portfolio to publishers. I met with Pantheon Books, and they wanted me to create artwork for a book of African tales which I did. But the Pantheon book fell through and the book went to another company that published non-illustrated books. For me, that would have been my entrance into the field, but it did not come about. Also, in the ’40s, I was offered by World Publishing Company to do a book of Richard Wright’s Black Boy (Harper & Brothers, 1945). It was unusual that you would illustrate one of his autobiographies, but I did the chapter headings. But that was that. That was all I ever got because it was black and I was black and that was the end of it.

It took a long, long time after that before I had a chance to do my work. It came about through an editor who heard about this man in the Bronx doing his books. Jean Karl, the editor at Atheneum, came to my studio and I spent the day with her. She had taken a look at the work I had been doing with Aesop’s fables, with Mother Goose, and with other drawings. I kept pulling out my paintings because I’m always painting, but it was the book work that she really came to see. After she left, she sent me a contract to begin working with Atheneum, and she gave me my first assignment which was one-line poems. And I worked with that for five or six years until it came out in 1967. When that was done, she said, “Ashley, I would like to use some of your African illustrations.” I said, “But Jean, I don’t like the way those stories are so academic and the way they are told.” She told me, “Ashley, you tell them in your own way.” And that is how my work with retelling African tales began.

Your parents were born in Antigua, and you were born in New York, yet African art and folktales have really resonated with you. What is it about the African culture that captures your interest, and what is your process for recreating and retelling the folktales?

Central to this is the fact that I am a black person, so I am interested in my culture. If it is not being given to me then I am going to do some searching to find it. As a child I was interested in folktales of the world—the Arabian folktales, the Hans Christian Anderson tales, and the stories of the Brothers Grimm. I also loved the African tales.

In my research I have been using the work of scholars who worked to get a written alphabet of the hundreds of tribal languages. They would have a phonetic transcription on one side of a page and a direct translation on the other side, and they would often ask for stories. “Tell me a story,” they would say. And they would get these stories which were oral tradition but were now written carefully in an academic form. All they would do was correct grammar in their translation, but they would not explore what it would mean in the oral tradition if it was spoken.

When I take one of these stories in my research, I work with stories that have been translated by English linguists, missionaries, scholars, or I can work with French and to a certain extent German as well because I studied in those countries. When I come upon a form I am interested in, I copy it down. Then my challenge is to find how in the writing to make a reader feel he or she is hearing a storyteller.

I infuse my prose with poetry—with the rhythms of poetry, the sounds, the beats. That is a challenge to find a way in my writing to open up the spirit of the voice, to express the sound of the voice in the printed word. That is what has excited me.

Experiencing Poetry

You said that you infuse your prose with poetry. Why has poetry found a place in your heart?

I love all poetry because it is at the heart of who I am. I loved all the Mother Goose, the Eugene Fields, the Robert Louis Stevenson, all of the poets. Later I learned the poems of black American poets: the Langston Hughes poems for children, the Countee Cullen poems for children. They were never part of my school work, but I found them through my family and through an outreach to include black cultural contributions in my learning as I grew.

Language through poetry means everything to me. Of course the force of poetry uses language in which the heart of what it means to be is always being tapped. And so it has helped me, perhaps, in trying to express myself. Poetry gets through to emotion.

One of the reasons I love Langston Hughes so much is that in his poetry, he can reach the smallest child in a very direct way; you do not have to work to understand what he had written. His clarity, his joy in writing, is so evident that I’ve always tried to get more of the work of this black artist across to young people so it would be on hand in the schools for use.

Is it important to formally teach a love of poetry or do you believe children will come to appreciate it on their own?

It is so important to teach poetry. I’m only doing this because as a child in elementary school we were given two or three weeks to go over the words of a poem and then stand before the class and speak it expressively. That is New York City Elementary in the Bronx where I grew up. Every day began with two or three students going up to the front and reciting expressively the words of a poem. Now on Fridays in the auditorium, two or three children from each class would go up on stage and speak poems to the assembly of grades. Then, at the end of each school year, we had elocution competitions where students would compete on grade levels of the best recitation of English and American poets. That never left me.

Appreciating Advancement

Over the years your work has been recognized as exceptional, including your poetry. You have been the recipient of numerous awards. What do those honors mean to you and do any stand out above the others?

The awards have meant everything to me. But when I am presented an award, I see it as being selected as one from a field of many who are doing their very best. I don’t see it as something that has come to me. I see it as coming to all of us who are working for the very best in books for young people. Everyone can’t get an award, but whoever gets the award is representing all of us.

Recently there has been great emphasis and discussion about the level of diversity in children’s books. Why is this conversation relevant and important? Why is it important to include diversity of themes and cultures in children’s books and illustrations?

This keeps being an area in which we make advances and then slow down and stop. The United States is a country made up of cultures from around the world, and these various cultures have contributed the best which has made the United States’ culture unique. And it is because of the diverse contributions that we have an American culture. It is very important that that be part of every child’s study. It does not matter who is in your class. It does not matter if you are in an area with one unified group. Learn about the people who make up the country in which you live. It is vital, it is important.

The discussion started with the1965 article by Nancy Larrick, “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” That is what shook up the field. Nancy Larrick was a wonderful person who I got to know and love. She came from a well-known family in Virginia, and she was working with black children in reading using picture books. One of the children looked up to her one day and asked, “Why are they always white?” Nancy Larrick did her studies and wrote the essay and shook up the field because it was something not to be spoken. She was never blocked after that; she kept going with the collecting of games, songs, stories, and poems for children.

Looking Forward

What are you working on now? Does it pertain to the advancement of multiculturalism?

There is always a lot to work on. At the moment I am working on my book for next year. It is full of poems of water by Langston Hughes. I’ve been doing collage illustrations for about 15 poems which I selected from his complete works that touch on waters, rivers, rain, whatever. I am just getting the final collage finished on that project.

I will also continue my work retelling African tales and selecting from the spirituals and doing those. I am always going back to the spirituals. They are so extraordinary and so accessible. I’ve never stopped working on ways to present the songs of the black American slaves. I’ve done six books of them, but there are thousands of those songs.

Do you ever plan to retire?

I don’t think artists know what retirement means, really. I always have a sketch book in hand. It doesn’t matter where I am or what it is, that sketch book will always be active whether I am on what you would call vacation or whatever. I don’t think of retirement. You must wake up as a child. You must wake up with the feeling of curiosity and adventure that [a] child faces when awaking.

When all is said and done, what do you hope your legacy will be? What is it that you want people to associate with your life and your work? What is the message you hope will live on?

Right now I’d like my interactions with people I meet to be meaningful in their life and in mine. It is a wonderful thing if you can be inspired by another. We always hope that the best we have to offer is what people will focus on. I love doing my work, and I love when people respond and enjoy it.

Ashley Bryan at home on Islesford. Photo by Bill McGuinness

Brief Bio

Ashley Bryan was born on July 13, 1923, in New York, New York. He grew up to the sound of his mother singing from morning to night, and he has shared the joy of song with children ever since. A beloved illustrator, he has been the recipient of the Coretta Scott King—Virginia Hamilton Lifetime Achievement Award and the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award; he has also been a May Hill Arbuthnot lecturer, a Coretta Scott King Award winner, and the recipient of countless other awards and recognitions. He lives in Islesford, one of the Cranberry Isles off the coast of Maine, where he can often be found with a cluster of children, all singing.

Ashley Bryan, The Author and Artist

- All Night, All Day : A Child’s First Book of African-American Spirituals

- All Things Bright and Beautiful*

- Ashley Bryan : Poems & Folktales

- Ashley Bryan : Words to My Life’s Song*

- Ashley Bryan’s ABC of African American Poetry*

- Ashley Bryan’s African Tales, Uh-Huh*

- Ashley Bryan’s Beautiful Blackbird and Other Folktales

- Ashley Bryan’s Puppets : Making Something From Everything*

- Beat the Story-Drum, Pum-Pum

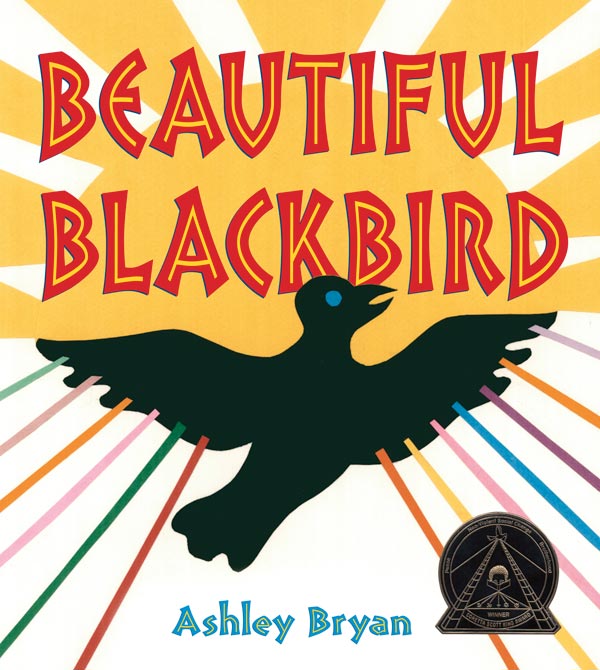

- Beautiful Blackbird*

- By Trolley Past Thimbledon Bridge

- Can’t Scare Me!

- How God Fix Jonah

- I, Too, Sing America : Three Centuries of African American Poetry

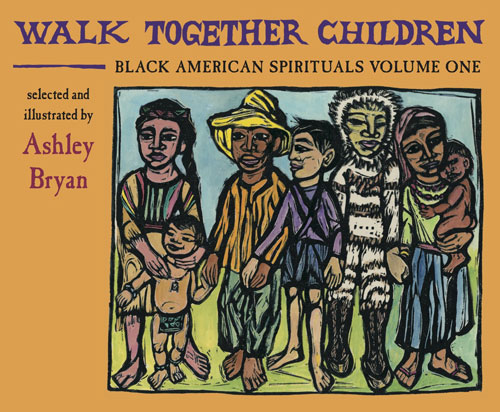

- I’m Going to Sing

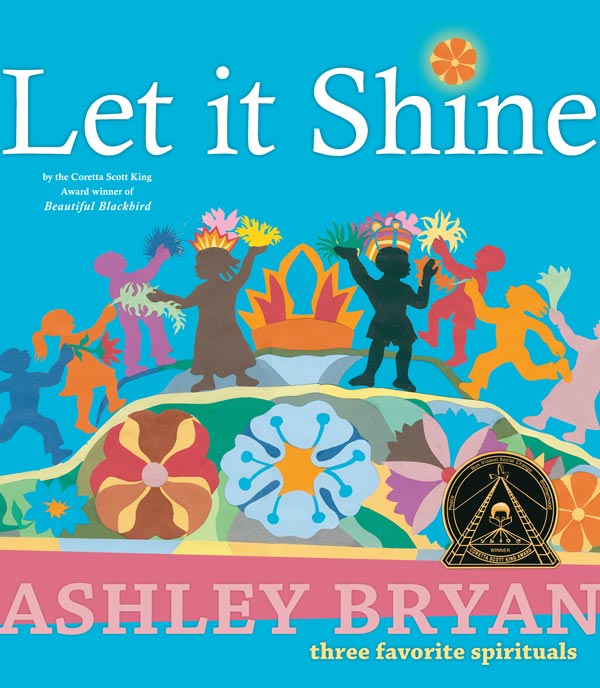

- Let it Shine : Three Favorite Spirituals*

- Night Has Ears : African Proverbs*

- Sun Is So Quiet*

- Walk Together Children

- What A Wonderful World

- Who Built the Stable? : A Nativity Poem*

*Ashley Bryan titles featured in Mackin’s Compendium

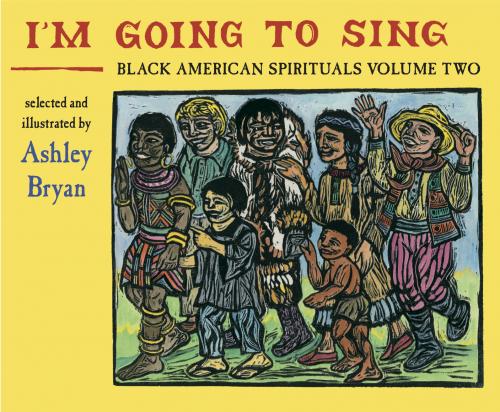

Ashley Bryan holds his print, “Sally Tea Cup” created for an upcoming compendium volume published by the London Children’s Museum. Photo by Henry Isaacs.

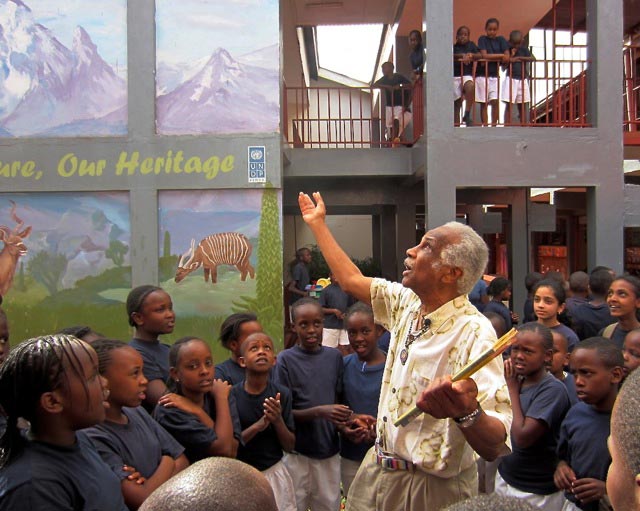

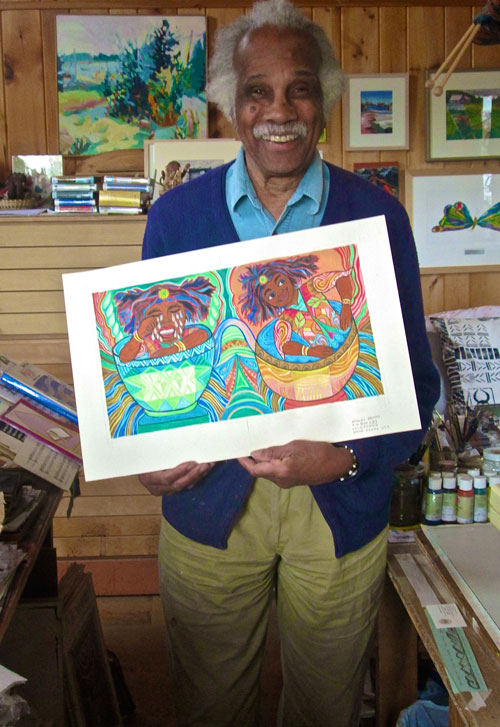

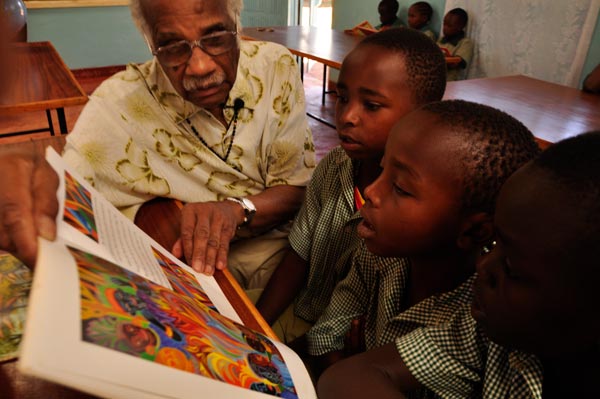

Ashley Bryan, The Humanitarian

For years Ashley Bryan has dedicated time, talent, and resources to philanthropic work around the world, especially in Africa where schools and libraries have been named in his honor. On a recent trip to Kenya and South Africa, Bryan interacted with children by sharing reading and singing experiences with them and making traditional stories and poems come alive as only he can do.

Ashley Bryan, The Soldier

During WWII, when he was just 19 years old, Ashley Bryan was drafted into the army. Though his high IQ ratings drew attention, he refused to attend Officer Candidate School and chose to stay with the 270 Port Company, 502 Port Battalion. After basic training, Bryan was stationed at the dockyards in Boston where he was assigned to serve as a winch operator handling cargo.

Though his job did little to feed his hunger for creative expression, he would draw in his spare moments. In fact, during his off-duty days, Bryan made friends with the neighborhood children and provided art supplies so they could all draw together. Later, when his battalion was shipped overseas, he continued to find ways to experience and express art such as when he received permission to attend the Glasgow School of Art in Scotland when not on duty.

No matter where he was stationed or what his duties were, Bryan continued his pursuit of artistic expression. Even today Bryan openly admits his ineptitude when it came to operating a winch. Fortunately, the men in his unit had great respect for him and supported his talent. They would take over his post and encourage him to draw instead.

Bryan was eventually sent to Normandy, France, and participated in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. He kept his sketch pad and art supplies in his gas-mask; they were with him when he landed on Omaha Beach. Even in war he continued to draw, but the subject matter weighed heavily upon him. Surrounded by pain, suffering, and death, Bryan’s joy in the free expression allowed through art was quelled.

After he was discharged from the Army, Bryan set aside his pursuit of creative expression. He had been so impacted by what he had seen and experienced that his mind was troubled by questions, questions, and more questions—questions such as why people would even choose war despite knowing the tragedies of it. After graduating from Columbia University with a degree in philosophy, Bryan still had no answers to the questions that plagued him, but he was ready to pursue creative expression again.

Deciding to dedicate himself to art, Bryan continued his education in Europe under the GI Bill. He first studied at the Aix-Marseille Université in France and then at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau as a Fulbright scholar. It was while he was in France that he experienced beauty so great that his hands were freed from the shackles of war.

While a student in France, Pablo Casals, a great cellist, broke his vow of silence to honor the 200th anniversary of the death of Bach. He planned to play at a series of concerts, and Bryan attended not only the rehearsals but also the first three concerts. It was during these practices and performances that the music freed Bryan’s hand allowing him to once again express himself through the rhythmic strokes of his pen and later his paintbrush.

Ashley Bryan could draw again.

Let it Shine

“The beautiful songs in this book are loved and sung freely throughout the world. Yet they were created by people who were not free—the African American slaves. The songs were originally called ‘Negro spirituals.’

“The beautiful songs in this book are loved and sung freely throughout the world. Yet they were created by people who were not free—the African American slaves. The songs were originally called ‘Negro spirituals.’

“It was a crime to teach a slave to read or write. However, the slaves’ urges to create could not be bound. In the freedom of the mind, their artistic gifts found expression for their hopes, sorrows, and joys in the creation of the spiritual. The slaves couldn’t write them down, but they could sing them! The spirituals are unique in the folk songs of the world and are considered one of the finest gifts to world music.” – Ashley Bryan, Let it Shine (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2007)

Beautiful Blackbird

“A long, long time ago, the birds of Africa were all colors of the rainbow … clean, clear colors from head to tail. Oh so pretty, pretty, pretty!

“A long, long time ago, the birds of Africa were all colors of the rainbow … clean, clear colors from head to tail. Oh so pretty, pretty, pretty!

“Back then, though, birds had no marks of black on their feathers. From the tops of their heads to the tips of their tails, no markings of black, uh-uh! Whether large or small, Blackbird was the only bird who had it all.” – Ashley Bryan, Beautiful Blackbird (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2003)

At a Hundred, I Shall Be a Marvelous Artist

“From the age of six, I had a mania for drawing the shapes of things. When I was fifty, I had published a universe of designs, but all I have done before the age of seventy is not worth bothering with. At seventy-five, I’ll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish, and insects. When I am eighty, you will see real progress. At ninety, I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At a hundred, I shall be a marvelous artist. At a hundred and ten, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age. I only beg that gentlemen of sufficiently long life take care to note the truth of my words.” – Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

Fan Mail

Ashley Bryan welcomes fans of his work to contact him at:

Mr. Ashley Bryan

c/o Atheneum Books

Simon & Schuster Publishers

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

About 10 years ago, a few of Ashley Bryan’s close friends began talking about the idea of preserving his legacy. In conjunction with members of Bryan’s family, this group of dedicated friends and family formed a board and established the Ashley Bryan Center. According to its mission statement, “The Ashley Bryan Center was created in 2013 to preserve, celebrate, and share broadly artist Ashley Bryan’s work and his joy of discovery, invention, learning, cultural understanding, and community.”

“The Ashley Bryan Center is something of which I had nothing to do,” says Bryan. “Four of the people on the island, two of my nieces, and my nephew believed that what I have been offering should be maintained in some way. I am deeply touched that they felt what I have offered could mean so much to others.”

“It is no accident that the Ashley Bryan Center chose the beautiful blackbird as its emblem,” notes Donna Isaacs, a founding board member. “Like Blackbird, who demonstrated the importance of inclusion, diversity, and self-worth in Beautiful Blackbird (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2003), Ashley treats everyone as ‘family.’ Blackbird represents Ashley’s deepest desire to kindle the creativity and celebrate the humanity within us all.”

The Ashley Bryan Center plans first and foremost to preserve and protect Bryan’s collections, intellectual property, and legacy. According to Isaacs, “We also hope to see the collection find a home in a place where it can be appreciated and used. Our long-term intention is to affiliate with an institution of higher learning where Ashley’s art, manuscripts, papers, collected works, and artifacts can be available for appreciation and study by scholars and the public.”

The center now owns all of Ashley Bryan’s extensive collections: paintings, drawings, writings, book illustrations, and countless toys and objects he has collected from around the world. This past summer, some of these assets were featured in the exhibition A Visit with Ashley Bryan. According to Isaacs, the exhibition was an opportunity to launch the center and to give visitors an experience of delight similar to what it is like coming into Bryan’s home.

“We also wanted people to have an opportunity to see Ashley as … a highly educated, sophisticated, worldly artist, poet, and writer, a WWII veteran of the segregated U.S. Army, and a great humanitarian. We wanted people to realize how broad his experience is and what a truly rich resource he is.”

The exhibition is currently at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Maine, through the end of February, 2015.

Discover more about the Ashley Bryan Center on Facebook.